eBook - ePub

International Partnership in Russia

Conclusions from the Oil and Gas Industry

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

International Partnership in Russia

Conclusions from the Oil and Gas Industry

About this book

International Partnership in Russia provides a unique insight into the joint ventures formed by international oil companies in Russia during the post-Soviet era. It outlines the highs and lows in their fortunes and analyses the reasons for their successes and failures.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access International Partnership in Russia by James Henderson,Alastair Ferguson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Économie & Commerce Général. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Turbulent History of Foreign Involvement in the Russian Oil and Gas Industry

Introduction

The history of the Russian oil industry dates back to the middle of the 19th century when oil was dug from pits near Baku, but the country’s emergence by 1900 as a major global oil producer had much to do with the involvement of foreign investors. Indeed the development of one of the world’s major oil companies, Shell, was based on its work in establishing production in southern Russia and a transport network to move its oil to the developing global market. In this chapter, we chart this early period of Russian oil history, which ended with the departure of foreign investors following the 1917 revolution, before describing the subsequent development of the Soviet oil industry. This occurred largely without foreign involvement, as first the oil fields in European Russia were brought on-stream in the 1930s and 40s and then the giant resources of West Siberia were explored and developed from the 1960s onwards. Russian oilmen remain rightly proud to this day of the achievements of their Soviet predecessors as they not only found and produced oil in vast quantities in the harshest of conditions but also constructed the massive infrastructure of rigs, pipelines and supply routes that still service the industry today.

However, as we describe in the second half of the chapter, the inadequacies of the Soviet command system, combined with a declining oil price in the late 1980s, led to increasingly desperate attempts to maintain oil production at the high levels of 10–11 million bpd that had been reached by that stage. When the collapse of the Soviet Union arrived in 1991 the consequent fall in oil production epitomized the decline in the then Russian economy, and we describe not only this fall but also how initially at least foreign companies were welcomed for the potential assistance they brought to arrest it. However, the emergence of wealthy and influential domestic entrepreneurs in the sector created a conflict of interest that caused significant turbulence for foreign companies, who were already struggling with the opaque legal and regulatory framework in the country. Although their help was wanted they were also viewed as potential competitors for cheap assets, and during the period of mass privatization in Russia during the late 1990s this led to ownership and governance issues which we describe in some detail.

The arrival of Vladimir Putin as Prime Minister and then President in 1999 has heralded a period during which the Russian state has re-asserted its position in the oil industry via its state-controlled companies Rosneft and Gazprom. This process in itself created initial uncertainty for all participants in the sector, but by 2003, despite the concern caused by the destruction of Yukos, foreign oil companies had started to return to Russia, led by BP and its investment in its huge partnership at TNK-BP. The subsequent decade has by no means been smooth sailing for foreign investors but has seen them gradually re-discover their position in the Russian oil industry, increasingly focused on partnership with the state companies or those closely related to them. As a result many of the major IOCs are now involved in partnerships that will help to develop the next stage of the Russian oil industry, developing offshore fields and unconventional resources to replace the gradual decline in the traditional oil-producing regions. This new set of partnerships means that foreign companies may be set to play as important a role in the future of Russian oil production as they did in its initial development 150 years ago, and this chapter aims to provide the historical context for a subsequent discussion of how this can occur in a manner that is beneficial for the Russian state and domestic and foreign investors alike.

The Russian oil and gas industry in a global context

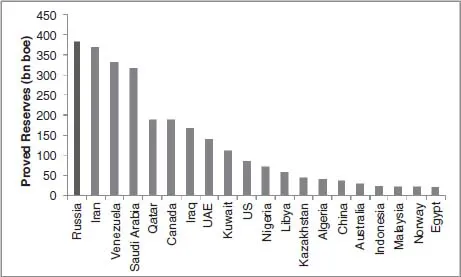

By an accident of geography and geology Russia contains the largest hydrocarbon resource base in the world and is the largest global producer of oil and gas combined. According to the BP Statistical Review published in 2012 the country contains 88 billion barrels of oil reserves and 45 trillion cubic metres of gas, while producing a combined total of approximately 20 million barrels of oil equivalent (boe) per day. On a graph of global hydrocarbon producers only Saudi Arabia, Venezuela and Iran come close to Russia, and its huge undiscovered resource base marks it out as a country not just of current importance but also of future growth for the oil and gas industry. In a recent survey, for example, the USGS1 estimated that two thirds of the world’s total Arctic resources, amounting to more than 250 billion boe, are located in Russian waters, and regions such as East and West Siberia, the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea are believed to contain a further 150 billion boe.2

It should therefore be no surprise that the world’s major oil companies are interested to seek investment opportunities amid this vast resource base, especially at a time when many of the world’s other large hydrocarbon producing areas are not always open to foreign involvement. Access to the huge reserves located in the Middle East is in many cases closed to outsiders or at least very difficult to achieve for domestic or geo-political reasons, while other prolific oil and gas regions such as Latin America, Africa and Asia carry their own political and economic risks. North America has re-emerged as an expanding hydrocarbon opportunity thanks to its shale oil and gas reserves, but nevertheless the huge resources located in post-Soviet Russia have demanded the attention of the global oil industry for the past 23 years, even if not everyone has decided that the potential rewards are worth the risk.

Figure 1.1 Top 20 countries by proved hydrocarbon reserves (2012)

Source: Graph created by author from data in BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2012

However, this situation is not unique to the 20th or 21st centuries, as in the 19th century Russia also offered an alternative investment location for oil companies excluded from the opportunities in the world’s largest oil producer at the time, the US. As we will discuss in the next section, the turbulence of the late Tsarist period offered huge opportunity for foreign players and even helped to create one of the world’s major oil companies, but also brought other investors to their knees as domestic politics wreaked havoc with the commercial landscape. The Soviet era then brought 70 years of exclusion for foreign companies as the USSR developed its giant fields and their attendant infrastructure alone, but low oil prices and economic decline in the 1990s finally brought the industry close to collapse. Since 1991 opportunities for foreign investment in the now Russian oil and gas industry have again emerged, but once again turbulence and volatility have been key features of the commercial environment. We therefore chart the history of the post-Soviet industry as a whole, before describing the changing role of foreign investors and the fate that befell them in the ever-changing world of Russian domestic politics, vested interests and changing commercial priorities.

The Russian oil and gas industry from the 19th century until 1930

Foreign investment was the key to the development of the early Russian oil industry

The history of the oil industry in Russia, the involvement of foreigners in it and the impact this has had on the global energy economy really dates back to the second half of the 19th century. At that stage 82 hand-dug pits were producing miniscule amounts of oil around Baku next to the Caspian Sea, and further development seemed unlikely thanks to the remoteness of the region and the incompetence of the Tsar’s administration. As a result, it was not until competitive private enterprise was allowed in the 1870s that the first oil wells were drilled and output began to increase rapidly.

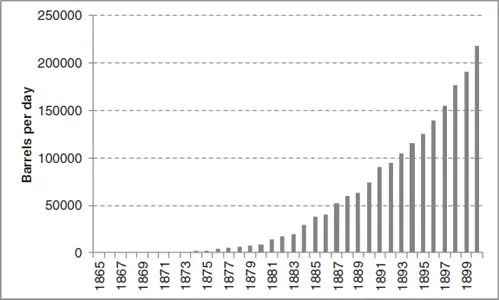

The key catalyst for entrepreneurial activity in the region was the introduction of an efficient public auction system for exploration and production leases in 1873, which extended the lease term beyond the previous four years and encouraged more serious investment. The result was that oil production expanded 15-fold over the next decade.3 The arrival of Robert Nobel to Baku in March 1873 was a further catalyst for growth in Russian oil production. A Swede whose father had emigrated to Russia in the early 19th century, Nobel became entranced with the opportunities that he saw for Russian oil, and having secured imperial blessing he set about acquiring oil assets and modernizing the industry. Learning from the experience of America, which had a 20- to 30-year head start on Russia, he improved drilling and refining technology, brought in more efficient business practices and consolidated his business into a major industrial concern.4 Most importantly he also improved the domestic transport system, building the first oil pipeline system in Russia and the first oil tanker in the world, which he used to move oil across the Caspian Sea and on to the major markets of Moscow and St. Petersburg.5 As a result the first significant Russian oil company was born, albeit that the Nobel Brothers Petroleum Producing Company was owned by foreigners.

The sharp increase in Russian oil production, combined with the introduction of hefty import tariffs, also created the first major clash in the global oil market. In the early 1870s the American oil industry had targeted Russia as a major potential export market, and by 1884 imports from the United States had reached 4,400 tonnes, three times the level of indigenous Russian production. By 1896, however, this had dwindled to an insignificant 22 tonnes, as the Russians not only had sufficient crude oil to supply their home market but also to seek to compete in the European export market.6

Figure 1.2 Russian oil production, 1865–1900

Source: Graph created by author from data collected from Alekperov, V. (2011) “Oil of Russia” and Yergin, D. (1990) “The Prize”

Despite the Nobel family’s success in saturating the domestic crude oil market, the limitations of domestic demand and the cost of transporting oil within Russia meant that any profit maximization strategy must involve exports. With the Nobel family dominating the domestic market, other Russian producers were also forced to look for alternatives, and following the defeat of the Turks by the Russian army at Batum in 1878, the possibility of an export route to Europe through the Black Sea became a reality. Two Russian producers named Bunge and Palashkovsky began to build a railroad from Baku over the Caucasus mountains to Batum. Running short of funds due to a fall in the oil price they turned to the Nobel family for assistance, but having been refused they found a new backer, the Rothschild family, who had been looking for an alternative crude oil supply for their Fiume refinery on the Adriatic coast in order to reduce their dependence on oil supplies from Standard Oil in the US.7 The railroad was completed in 1883–1884, and Russian oil exports then expanded rapidly. Indeed by the end of the century Russia had become the world’s largest oil producer and exporter,8 initiating the first major struggle for domination of the global oil market.

Despite an initial attempt by Standard Oil to react to this new competition by cutting oil prices, Russian crude oil became firmly established in the European and Asian markets, with the latter being a particular region of competitive strength.9 Indeed the Shell Oil Company, now Royal Dutch Shell, was founded on its owner Marcus Samuel’s entrepreneurial insight that the export of Russian kerosene to the East could be facilitated by the use of the Suez Canal and the building of storage depots throughout the Asian continent.

However, in a foretaste of events later in the 20th century, the rapid expansion of Russia’s oil industry was to lay the foundations for its first period of stagnation. So productive were many of the wells drilled in the Caucasus in the late 19th century that little thought was given to production planning, improving technology or conservation. By 1900 3,000 wells had been drilled in the Baku region alone,10 but Russian output then peaked in 1901 at just under 12 million tonnes (240 thousand bpd), at which point it was contributing 7% of the country’s export earnings.11 However, this level of output was not achieved again for almost three decades. The continued use of primitive production methods and a failure to import more modern techniques from the West was one major factor in the stagnation of the early 20th century, with the primitive and dangerous sump production method used in the 1860s still being employed by some producers in 1913.12 However, corporate rivalry, commercial scheming, a changing fiscal regime and domestic political unrest also contributed to unease among producers and a reluctance to invest in output growth. In particular competition for global market share led to the oil entrepreneurs cutting world prices for kerosene at a time when the Tsarist authorities were attempting to increase their share of oil revenues by changing the concession system.13 This clearly undermined the economics of investment in the oil industry at a time when the political risks were being increased by a series of wildcat strikes initiated by amongst others a young Joseph Stalin. These reached a climax in 1905 with the first revolution against the Tsarist regime, leading to a 3 million tonne drop in oil output that year alone. Although the situation improved enough over the next few years for Royal Dutch Shell (as it had become) to feel confident enough to buy out the Rothschild family oil interests in 1911, Russian output did not recover significantly prior to the 1917 revolution. Again, in a harbinger of future disputes, blame for this continued stagnation was placed by some at the door of the “oil magnates”, who were accused of encouraging under-investment in order to protect their own monopoly positions.14 Whatever the underlying cause, by 1913 Russia’s share of world exports had fallen from a peak of 31% to only 9% and by the time of the revolution in 1917 output had fallen to below the level it had been at the turn of the century.

The advent of the Bolshevik revolution in 1917 brought a further collapse in output, with production in 1918 being less than half the level seen just one year before. Interestingly, though, despite the formal announcement of the n...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Acknowledgements

- Note on Transliteration

- List of Abbreviations

- Conversion Factors

- Preface

- 1 The Turbulent History of Foreign Involvement in the Russian Oil and Gas Industry

- 2 A Review of Academic Theory on Joint Ventures, Partnership and the Importance of Local Knowledge

- 3 Joint Ventures from the 1990s

- 4 The Key Drivers of Foreign Partner Success – A Quantitative Analysis

- 5 Experiences in the Putin Era

- 6 Reflections on Partnership at TNK-BP

- 7 Conclusions on a Strategy for Foreign Partners

- Appendices

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index