eBook - ePub

Corporate Foresight and Strategic Decisions

Lessons from a European Bank

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Corporate Foresight and Strategic Decisions

Lessons from a European Bank

About this book

This study investigates the relationships between corporate foresight and management decision-making processes in organizations. It provides an extensive analysis of extant theories of corporate foresight and strategic management, brings in new insights, and presents an in-depth case study exploration of corporate foresight of a European bank.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Corporate Foresight and Strategic Decisions by S. Marinova,R. Ul-Haq,Kenneth A. Loparo,Kenneth A. Loparo,Claudio Gomez Portaleoni,Marin Marinov in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business Communication. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Literature Review

Strategic management research

This research aims at understanding the corporate foresight phenomenon and its impact on strategic decisions in the context of the European banking sector. As corporate foresight is predominantly concerned with the future-oriented direction of an organization, the study is embedded in a sub-domain of strategic management. More specifically, corporate foresight refers to the organization’s commitment to providing a view on the future for future business areas (Gruber and Venter, 2006). With regard to the research approach underlying the investigation, the following section will provide an overview of different perspectives on strategic management research and position corporate foresight within this field.

Definition of strategy in strategic management research

From a historical point of view, the concept of strategy can be traced back to semantic uses in the Old Testament. Later, the term was used in military and political contexts by authors such as Clausewitz, Machiavelli and Bismarck until it was finally integrated into management research. The term ‘strategy’ has its origin in the ancient Greek word strategos, which means ‘general’, and is further rooted in the terms for ‘army’ and ‘to lead’. The derived verb stratego reflects the plan to destroy enemies by effectively employing resources (Bracker, 1980; Grant, 1998).

In the early stages of strategy and management research, Alfred D. Chandler (1918–2007) made a major contribution to the scientific development of these concepts. In his studies of corporations such as General Motors, DuPont, Exxon and Sears, he concluded that strategy refers to the organization’s determination of long-term goals and objectives by allocating resources to achieve these and setting courses of action. In line with his argument, decisions are an integral part of strategy, as they reflect the application of activities to expand the volume of activities (Chandler, 1997).

Particularly in the years after the mid-twentieth century, the concept of strategy became the subject of extensive discussion and research in academia (Chandler, 1962; Ansoff, 1965; Pettigrew, 1992; Mintzberg, 1994; MacKay and McKiernan, 2004a; Ezer and Demetis, 2007), when a clear understanding and delineation of ‘what strategy is’ still called for profound investigation. An answer to this problem is even more of a dilemma because the concept is widely used, but only limitedly grasped, and is interchangeably used in academia with other terms such as ‘strategic planning’, ‘strategic management’ and ‘scenario planning’ (Godet, 2000). Against this background, Mintzberg, one of the most prolific researchers in the area of strategic management, describes strategy in the following way:

One of the more important things managers do is make strategy for their organizations, or at least oversee the process by which they and others make strategies. In a narrow sense, strategy-making deals with the positioning of an organization in market niches, in other words, deciding on what products will be produced and for whom. But in a broader sense strategy-making refers to how the collective system called organization establishes, and when necessary changes its basic orientation. Strategy-making also takes up the complex issue of collective intention – how an organization composed of many people makes up its mind, so to speak.

(Mintzberg, 1989, p. 25)

Based upon Mintzberg’s description of strategy, three main points can be identified: (i) strategy is something made by managers. This stresses that strategy is highly dependent on the human element (Johnson et al., 2008); (ii) strategy refers to the positioning of the organization in markets – with particular reference to the organization’s products and customers; and (iii) strategy is a dynamic concept involving organizational change and collective minds.

Among different definitions in the literature, a generally accepted conceptualization of strategy considers the impact on the organization’s scope and direction over the long term; the achievement of a competitive advantage and performance by the management of resources and competences in an ever-changing environment; the consideration of stakeholders’ expectations; and the development of an independent view about future opportunities and risks (Bourgeois, 1984; Hamel and Prahalad, 1994; Drucker, 1999; Argyres and McGahan, 2002; Goldman, 2007; Johnson et al., 2008).

Strategic decision-making, which is an integral part of strategy, will be discussed in detail later in this book. The following section will explore different perspectives of strategy and strategy research.

Perspectives on strategy and strategy management research

Despite the long history of strategic management research, it has failed to find a consensus between diverging perspectives, but instead has generated a “bewildering array of competing or overlapping conceptual models” (Hart, 1992, p. 327). Two differing approaches can generally be identified in strategy research: (i) the normative (prescriptive, deliberate) and (ii) emergent (descriptive, positive) approach. While the former refers to what the firm’s strategy should be, the latter is concerned with the firm’s actual strategy (Mintzberg, 1989; Burgelman, Maidique and Wheelwright, 1996).

The normative approach in strategy research has mainly been established by Chandler (1962), Ansoff (1965), Andrews (1971) and Porter (1980). In more recent publications, the normative approach has also been termed ‘rational’ (Hart, 1992) or ‘classical’ (Whittington, 2000). In essence, the normative approach considers profitability as the highest goal of business, thereby assuming that managers are ready and confident when employing profit-maximization strategies through rational long-term planning (Mintzberg, 1989; Whittington, 2000).

In contrast, the emergent approach to strategy criticizes the normative approach by emphasizing the organization’s heterogenic nature and the general instability of business environments. Due to these conditions, strategies cannot be programmed a priori, but, rather, evolve or emerge over time (Mintzberg and Waters, 1985). The emergent approach to strategy has mainly been introduced by the McGill research group led by Mintzberg and his colleagues (Mintzberg and Waters, 1985; Mintzberg, 1989, 1994), who assert that strategy is dynamic in nature and thereby plans should adapt according to results and changes in the internal and external environment of the organization (Mintzberg, 1978; Gibbons and O’Connor, 2005).

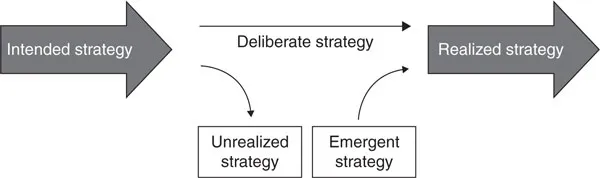

Based upon the different perspectives on strategy and the way in which strategy comes into existence, a widely used model of strategy-making has been established in strategic management research which stresses the process by which strategy is intentionally formulated and subsequently partially put into realization. The realized strategy mirrors the convergence of deliberate (intended) and emergent strategy (Mintzberg and Waters, 1985; Mintzberg, 1989; Hitt and Tyler, 1991; Brews and Hunt, 1999; Whittington, 2000). A model of these types of strategy – from a process perspective – is displayed in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Types of strategies

Source: Adapted from Mintzberg and Waters (1985).

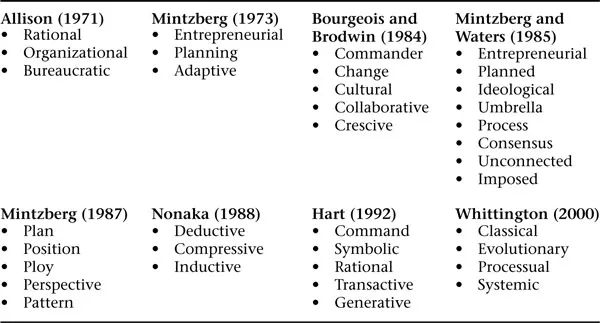

Table 1.1 Selected perspectives on strategy and strategy-making

Source: Adapted from Hart and Banbury (1994); Johnson et al. (2008); Whittington (2000); Hart (1992).

Apart from Mintzberg’s conceptualization of strategy, several other different perspectives on strategy and strategy-making have arisen in management research. Although Mintzberg’s model is predominantly represented in strategy research (Hitt and Tyler, 1991; Brews and Hunt, 1999; Davies and Walters, 2004), further investigations and strategic models, such as the planning perspective (Mintzberg, 1973; Nonaka, 1988) and an evolutionary perspective (Alavi and Henderson, 1981; Whittington, 2000), have also contributed to our knowledge in this area. An overview of various perspectives on strategy from selected researchers is given in Table 1.1.

Apart from these various perspectives on strategy, management studies generally distinguish between the content and process perspectives of strategy research (Montgomery Wernerfelt and Balakrishnan, 1989; Leong et al., 1990; Pettigrew, 1992; Hodgkinson and Sparrow, 2002; Elbanna and Child, 2007):

i) The content perspective usually refers to the conditions and type of strategy employed. The content can therefore include decisions regarding portfolio management, diversification, internationalization and the alignment of firm strategies with environmental characteristics (Fahey and Christensen, 1986; Elbanna, 2006; Johnson et al., 2008);

ii) Process research, in contrast, arises from the assumption that people and the world are too complex and too imperfect for rigorous economic research. Thus, against the background of unsystematic conditions within organizations, process research recognizes and includes the imperfections and complexities arising from conditions such as organizational culture in the analysis. Process research specifically focuses on the way by which managers change the firm’s strategic position through the strategic decision-making process (Elbanna, 2006; Johnson et al., 2008). The scientific areas from which strategy processes gain important contributions include psychology, political science and ethics.

Since this research aims to understand how corporate foresight is manifested and occurs in organizations (process), rather than to evaluate the different pictures of the future designed at the subject organization under investigation (content), the research will analyse the phenomenon from a process – as opposed to a content – perspective. The following section will describe how both strategy processes and corporate foresight are conceptually connected and suggest a further approach for studying the concept.

Location of corporate foresight research within strategic process research

We consider strategy – and specifically strategic decision-making – as the conceptual basis to use for analysing the corporate foresight phenomenon. Both strategy and corporate foresight share two main elements that link them together, namely, the long-term consideration of the future by creating an independent view and understanding what is still to come (Bourgeois, 1984; McMaster, 1996; Fahey and Randall, 1997; Becker, 2003; Voros, 2003; Chermack, 2004; Schwarz, 2008a). More specifically, the main concern of corporate foresight, which understands the future for the benefit of the organization, categorizes the phenomenon as part of strategic management (Gruber and Venter, 2006).

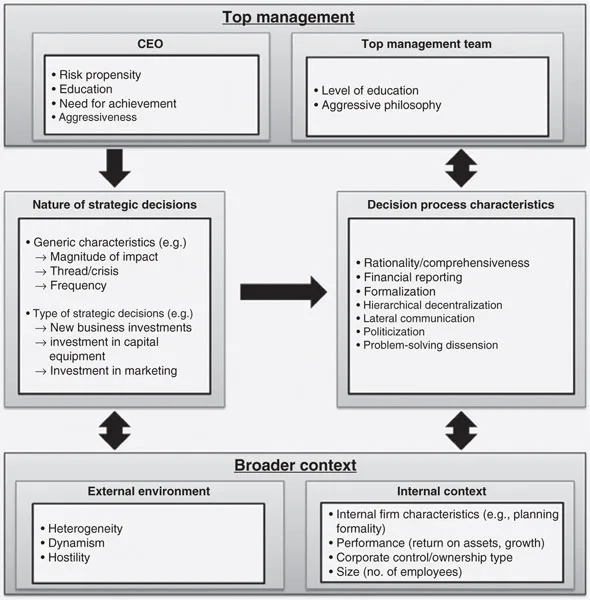

In more recent strategy research, scholars have attempted to design integrated frameworks that acknowledge the different streams in strategy literature. Papadakis, Lioukas, and Chambers (1998) propose that four main elements are related to strategic decision-making which reflect its process in the organization.

i) Top management: the top management perspective on strategy and strategic choice traditionally refers to management characteristics influencing corporate strategy (Hambrick and Mason, 1984; Miller and Toulouse, 1986; Hambrick, 1987). The main argument of this perspective criticizes the traditional, deterministic perspective, which states that the outer environment is the predominant factor in shaping the organization’s strategy. Instead, it is argued that top managers make choices based on corporate strategy, hence reflecting an internal behavioural aspect of strategy-making (Child, 1972; Hambrick and Mason, 1984; Miller and Toulouse, 1986; Hambrick, 1987; Geletkanycz and Hambrick, 1997).

ii) Nature of decision-making: researchers have argued that managers classify decisions before the actual decision-making process – and in turn change the process according to this classification (Mintzberg, Raisinghani and Théorêt, 1976; Dutton, Fahey and Narayanan, 1983; Fredrickson et al, 1984; Sharfman and Dean, 1991). More recent research in the area agrees with this view by emphasizing that strategic decision characteristics (generic attributes and objective categorization) significantly shape the decision process (Papadakis, Lioukas and Chambers, 1998).

iii) Decision-process characteristics: decision processes have traditionally been investigated by analysing process dimensions such as comprehensiveness and rationality (Dean and Sharfman, 1993), political and problem-solving (Lyles, 1987) and the actual phases of decision processes (Mintzberg et al., 1976).

iv) Broader context: the broader context consists of the internal context and the external environment. The former refers to specific organizational criteria such as performance and size (Child, 1972; Bourgeois, 1981; Fredrickson and Iaquinto, 1989; Papadakis, Lioukas and Chambers, 1998), whereas the latter focuses on environmental characteristics such as dynamism and hostility (Hofer, 1975; Eisenhardt, 1989; Fredrickson and Iaquinto, 1989; Hitt and Tyler, 1991; Papadakis, Lioukas and Chambers, 1998). The consideration of the broader context implies that organizational strategy and decision-making are significantly impacted by external factors and not just internal factors such as managers’ characteristics and personalities.

An overview of the integrated framework of Papadakis, Lioukas and Chambers (1998) is displayed in Figure 1.2.

The framework of Papadakis, Lioukas and Chambers (1998) is helpful in understanding corporate foresight because it is a holistic approach that integrates different perspectives and dimensions in strategy research. Although they are specifically focused on strategic decisions rather than on strategy and strategy-making, it can be argued that the elements mentioned in the framework address the most important factors in understanding organizational reality.

Based on this framework, the following conceptual links are drawn between strategy, strategic decision-making and the corporate foresight phenomenon:

i) From an internal and behavioural perspective, managers play a crucial part in the organization’s strategy-making due to their role in making strategic choices (Child, 1972; Hambrick and Mason, 1984; Montanari, 2007). This implies that the organization’s long-term orientation is contingent upon the human element of strategy (Johnson et al., 2008). Considering that corporate foresight mainly deals with the future, which in turn is related to managers’ beliefs, hopes, emotions and expectations regarding the future (Reading, 2004), a managerial perspective is highly appropriate to be included as well as shared by both concepts.

Figure 1.2 Factors influencing strategic decision-making processes

Source: Adapted from Papadakis, Lioukas and Chambers (1998).

ii) The organization reflects the internal dimension of the strategy context. Although the management makes choices regarding the organization’s structures, processes and resources, it constricts the top managers’ decisions at the same time (Romanelli and Tushman, 1986; Papadakis, Lioukas and Chambers, 1998). As previous research has suggested, corporate foresight, too, appears to be the subject of similar influences in terms of its responsiveness to organizational characteristics (Becker, 2003; Gruber and Venter, 2006; Rollwagen et al., 2006). As a result, an internal organ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. Literature Review

- 2. Conceptual Framework and Theoretical Considerations

- 3. Methodology

- 4. The European Banking Sector

- 5. The Bank

- 6. Data Analysis and Findings

- 7. Discussion, Contributions and Directions for Future Research

- Appendices

- Notes

- References

- Index