- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book reviews the remarkable growth, diversity and challenges of child sponsorship. It features the latest progress in child sponsorship practice and necessary tensions experienced by some organisations as they seek to maximise impact.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Child Sponsorship by B. Watson, M. Clarke, B. Watson,M. Clarke in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Development Economics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction to Key Issues in Child Sponsorship

Brad Watson and Matthew Clarke

Introduction – The child sponsorship phenomenon

Child Sponsorship (CS) is a humanitarian phenomenon and its broad popularity combined with a prodigious ability to mobilize funds for international non-governmental organizations (INGOs) is unique in the humanitarian aid sector. Writing in the mid-1990s, Smillie (in Sogge et al, 1996, p.99) described CS as ‘the bedrock of several of the older organizations’ and ‘one of the most enduring success stories in private aid agency fundraising’. In the same year that the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) were launched, Brehm and Gale (2000,p.2) noted that ‘agencies which run such programmes report a year-on-year increase in both the number of children sponsored and the amounts of money raised’. The prominence of CS as a fundraising device has continued with the first decade of the twenty-first century witnessing sustained growth in what can be loosely termed the CS sector. In North America, Europe, the United Kingdom and Australia, INGOs that have invested in CS as a key marketing tool are amongst the largest private aid agencies in terms of annual funds raised. The volume of children assisted is especially noteworthy. According to Wydick et al (2009, p.1) in 2009 the number of children in the world who were sponsored was between eight and 12 million, and the subsequent flow of funds exceeded US$3.1 billion. By such accounts it is possible that over two decades CS has generated international transfers in excess of US$50 billion.

Although there are numerous INGOs utilizing CS, a small number of them tend to be more prominent in Northern countries. For example, in 2007 the three largest Canadian CS INGOs generated ‘more than ten times as much money from the public as the three top non-sponsorship organizations’ (Plewes and Stuart in Bell and Coicaud, 2007, p.30). The situation in Australia, where World Vision is the largest INGO, is even more intriguing. World Vision Australia’s annual 2008–2009 income was more than five times greater than the next largest INGO (ACFID, 2012). In the year 2010–2011, total international income in Australia for Save the Children, World Vision, Compassion, Plan, Children International and ChildFund exceeded US$6 billion, at least US$2.5 billion of which derived from CS. Far from being a spent force, CS is a tool that has paved the way in some INGOs for rapid growth and leverage to access government grants (Maren, 1997, p.145), a sustainable income stream, a more diversified funding base and the consolidation of a small number of INGOs into ‘super-sponsors.’ The success of CS in mobilizing public donations has elevated several CS INGOs (especially the early adopters) into an elite category of fundraisers. As a ‘product’ in the market place, CS can therefore be considered a great success and the fact that CS fundraising methods have remained relatively popular over time is remarkable.

Although CS activities across INGOs are not uniform, they do have a number of common characteristics including a historic emphasis on regular giving, the motivation of donating to benefit individuals, and the provision of regular updates for the benefit of sponsors. In linking individual children to geographically distant donors, CS is credited with personalizing giving and making, as Fowler (1992) suggested, distant obligation seem immediate and personal. Children are key to the enduring appeal of CS to donors and while there is a continuum of modes for utilizing the funds raised through CS (from direct cash handouts to beneficiaries, to larger community development activities and community mobilization) the child as core has remained largely intact over time. Consequently the reputations and identities of CS INGOs are inextricably and profoundly linked to children although the extent to which children serve INGOs as symbols of world harmony, seers of truth and embodiments of the future (Bornstein, 2003, p.7) is debatable.

The emphasis of CS INGOS on children and their needs has legitimized and depoliticized their activities historically. It is argued by Manzo (2008, p.632) that the iconography of childhood expresses institutional ideals and key humanitarian values of solidarity, impartiality, neutrality and humanity. However, there can be no doubt that as a motivator for private donors and a legitimizing imperative for INGOs, the sponsorship of children works. Commenting on aid appeals in general, Coulter (1989, p.1) observed that ‘the wide-eyed child, smiling or starving, is the most powerful fundraiser for aid agencies.’ Notably, much of the contentious historic debate over CS fundraising has focussed on its truthfulness and the extent to which CS INGOs have portrayed developing country beneficiaries with respect and dignity (Mittelman and Neilson, 2009, p.64). This has led some to question whether the formation of a relationship based on exchange of money ‘may perhaps be a source of dissonance in sponsors’ (Yuen, 2008, p.50).

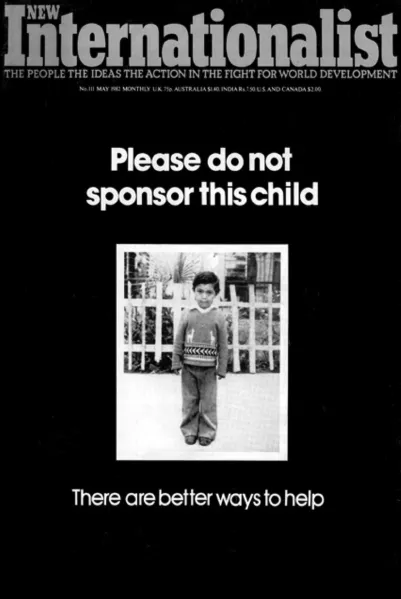

The CS literature

Scholarly scrutiny of CS interventions has been very limited and there is an acute shortage of quality research regarding the impact of historic interventions. In one attempt at a literature review, Brehm and Gale (2000, p.1) observed that there was ‘…a scarcity of empirical research-based evidence about the impact of child sponsorship on recipient families and communities’. Unfortunately, the situation remains little changed at the time of writing this chapter. Available information about CS typically falls into the three broad categories of easily accessible journalistic exposé, carefully selected in-house publications (including consultancy reports) and a fragmented scholarly literature. Despite some exceedingly rare efforts to quantify the impact of sponsorship interventions (Wydick et al, 2013), and a small number of contributions from anthropologists (Bornstein, 2001, 2003), CS interventions are characterized by an abundance of anecdotal, often negative accounts dating to the 1980s. Such accounts have continued to inform the widespread criticisms of CS that emerged when the New Internationalist magazine addressed the topic in several issues during the 1980s (Stalker, 1982).

Generally speaking, CS is heavily contested, poorly understood and under-researched, a point made in Chapter 4 which deals with historic criticism of CS. That so few scholars and industry insiders have sought to interrogate the emergence, evolution and contribution of CS INGOs makes it difficult to evaluate their legitimacy, especially in the absence of a large body of evidence on the impact and effectiveness of non-CS INGOS noted by Edwards and Hulme (2002, p.6).

A technical approach to evaluating the legitimacy of INGOs involves comparative judgments based on perceptions of accountability, representativeness and performance (Lister, 2003, p.3). Fowler (1997, p.188) asserts for example that demonstrating satisfactory levels of achievement is the first step on the legitimacy ladder. Like other INGOs, CS organizations are eager to do good and consequently they are prone to critical self-reflection. Meadows (2003, p.109) asks, ‘Does Child Sponsorship ever go wrong? Of course. Is that a good enough reason to abandon the concept?’ It is perhaps the pre-eminent question that has occupied staff in CS INGOs for the past 20 years as they have considered both marketing imperatives and the impact of CS-related humanitarian interventions in terms of what really makes an impact. This question of efficacy and legitimacy is paramount. Harris-Curtis (2003,p.1) observes that in addition to INGO self-reflection ‘The reality for NGOs today is that they are increasingly challenged by the media, public, governments and academia.’ While this may be the case, large CS INGOs have been especially sensitive to criticism that programmes are out of step with ‘best practice’.

Figure 1.1 New Internationalist front cover

From the early 1980s the individual support of children through CS was increasingly questioned (Stalker, 1982, p.1)

At a time when the ‘halo of saintliness’ around INGOs is under threat (Racelis in Bebbington et al, 2007, p.203) can it be demonstrated that CS INGOs are thinking, learning organizations committed to improvement even though they may not have transitioned from a mind set of aid for individual welfare, to development as delivery beyond to development as leverage? (Edwards et al, 1999, p.15). Is CS an impediment to change or a vehicle for innovation? In Chapter 5 Moran and others argue that for Save the Children International CS has, over the past decade, become a flexible source of funding for creative, lasting change. Chapter 3, which features the evolution of the ChildFund and Plan International’s programmatic approach, proposes a typology of CS funded activity. It suggests that change and critical self-reflection is a feature of large CS funded INGOs though to what extent expectations of sponsors contribute to mandates for change is unclear.

Keeping in mind Fowler’s ‘onion-ring’ strategy for INGOs, we might ask if CS INGOs have a credible ‘core’ of projects and successive ‘skins’ or ‘layers’ of important activity including research, evaluation, advocacy, campaigning and public education, with a commitment to human rights and structural reform? Or are they merely ‘ladles in the global soup kitchen’, prone to choosing a path of least resistance? (Fowler in Edwards and Fowler 2002, p.22). In Chapter 9 of this book Sim and Peters discuss the Compassion model of intervention, an approach that places holistic child development at the centre or core of intervention logic. In keeping with UNICEF’s argument that children living in poverty ‘experience deprivation of the material, spiritual and emotional resources needed to survive, develop and thrive’ (UNICEF in Minujin et al, 2006, p.485) Sim and Peters prod us to consider who decides which CS core activities are credible and whether religion and child development are synergistic.

Although there appears to be a dearth of published research demonstrating CS INGO engagement in robust evaluation, most large CS INGOs do capture data to identify programme impact, flaws and tensions. Although such information has often been lost in the ‘grey literature’ of confidential INGO project records there is a recent, albeit limited trend to publicize findings and learnings, examples of which are found in Chapter 6 where the authors discuss the transition of Plan International’s development programming from a traditional service delivery model towards a rights-based approach and how this strategic shift has interacted and is interacting with Plan’s sponsorship model. Given its emphasis on rights-based interventions, Plan may be seen as an organization committed to a theory of change model in which ‘capacity changes of young people and duty bearers are expected to trigger citizenship changes whereby young people become aware of their power and use this to effectively participate in decision-making processes’ (Williams and Kantelberg, 2011, p.2).

The tensions evident in CS advertising have received considerable attention from academics however given that CS is one of the primary portals through which private donors in the North may view (and to an extent experience) the South, how can CS INGOs not only educate their supporters, but deepen understanding of structural causes of poverty so that sponsors become partners, advocates and activists? In her chapter Tallon addresses the issue of global citizenship education for school students and asks how CS INGOs can engage in development education in ways that dignify the poor, avoid harmful stereotypes and deal with the causes of poverty rather than the symptoms. Critical to such an approach is avoidance of aid discourses that rely on the benevolence and politics of poverty associated with charity and what has been disparagingly referred to as the White Man’s Burden (Jefferess, 2008, p.34). Accordingly, CS INGOs are said to embrace a test of their credibility when moving beyond the self-serving task of marketing children as passive products, to the more complex task of advocating with children and their communities, for the realization of child rights as a purposeful way of reducing poverty.

Child: Product or purpose?

The post-World War Two era saw the United States and Western Europe prosper, an acceleration of globalization, and a growing interest in the conditions of the poor in ‘undeveloped nations’ accompanied by the running down of the era of traditional missionary endeavour and direct colonialism. In this nexus of events, it had never been so easy to offer direct support to individuals in far-flung places. The widespread dissemination of a note, found pinned to a small child by either journalist John Langdon-Davies or relief volunteer Eric Muggeridge during the Spanish civil war in 1937, is characteristic of many post-World War Two appeals for sponsorship that would prove popular: ‘This is Jose. I am his father. When Santander falls I shall be shot. Whoever finds my son, I beg him to take care of him for my sake’ (in Mittelman and Neilson, 2011, p.371). This emotive, brief request contains several potent themes of past CS marketing including urgency, appeal to paternal or maternal instinct, lost innocence and a sense of very personal need. This poignant message first informed, then sought compassion and finally urged action, enlisting members of the general public in the ongoing provision of food, shelter, education and child-oriented services for the benefit of individual children. However, this was certainly not the first foray into CS.

It is interesting that to date there has been a lack of consensus on which organization pioneered CS. The origin and characteristics of early CS programmes are discussed by Brad Watson in Chapter 2, which traces early CS practice to at least 1919, in a joint sponsorship programme run between the newly established Save the Children Fund in the UK and the Society of Friends in the Austria. There it was initially used for the provision of food rations to middle-class children who were not eligible for aid provided by the American Relief Administration feeding programme. The common perception that CS did not emerge until the late 1930s and early 1940s is incorrect. Referring to Save the Children Fund sponsorship of British children, Freeman (1965, pp.49 & 89) observed that during the Great Depression there were British children ‘with limbs like broomsticks’ and ‘grotesque swollen abdomens’. Save the Children UK responded indicating that ‘individual children put forward by teachers or medical officers as in great need of help were “adopted” by benefactors who not only paid the sponsorship subscription, but took an interest in the child or family or school with letters, presents and even visits’. It would seem that in the 1930s CS was offered to a small number of citizens in the UK and USA for the support of children in their own countries.

Freeman notes that by 1963 there were just 715 individual children and 169 families being helped by UK friends in ‘other’ countries. Nevertheless, despite its humble beginnings, popular support for international CS increased dramatically and was adopted with great success by other organizations such as World Vision, featured in Chapter 7. This may be attributable to a combination of effective marketing and the fact that although many donors have been overwhelmed at the seeming futility of addressing global poverty, ‘the genius of sponsorship is that it links a caring donor with a needy child in the Third World’ (Waters, 2001, p.5). In some cases it has nurtured direct contact with families of sponsored children. Freeman (1965,p.142) remarks on the personal link forged between some sponsors and adult beneficiaries, quoting a letter from a widow in a German refugee camp to her sponsor: ‘It is thanks to you that I did not lose my courage… What a comfort to know that someone, however far away, knows your name and that of your children. Around here is no one, only misery, but your help is a solid rock beneath my feet.’

Bornstein (2001, p.601) reminds us that the western perception of children as valuable for their innocence and emotional value may not be consistent with the way children are viewed in their community of origin. Commentators have also observed the potential for negative impacts of some CS funded interventions on recipients, referred to in media exposés as formation of unrealistic expectations, dev...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Abbreviations

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on Contributors

- 1 Introduction to Key Issues in Child Sponsorship

- 2 Origins of Child Sponsorship: Save the Children Fund in the 1920s

- 3 A Typology of Child Sponsorship Activity

- 4 Issues in Historic Child Sponsorship

- 5 Excellence or Exit: Transforming Save the Children’s Child Sponsorship Programming

- 6 Child Sponsorship and Rights-Based Interventions at Plan: Tensions and Synergies

- 7 World Vision – Moving Sponsorship Along the Development Continuum

- 8 Compassion International: Holistic Child Development through Sponsorship and Church Partnership

- 9 Children at the Centre: Children International, Child Sponsorship and Community Empowerment in Underserved Areas

- 10 Baptist World Aid: Transition to a Child Centred Community Development Approach

- 11 Through the Eyes of the Sponsored

- 12 World Vision, Organizational Identity and the Evolution of Child Sponsorship

- 13 Give and Take? Child Sponsors and the Ethics of Giving

- 14 Child Sponsorship as Development Education in the Northern Classroom

- 15 Child Sponsorship: A Path to its Future

- Index