eBook - ePub

Climate Innovation

Liberal Capitalism and Climate Change

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A comprehensive examination of the inability of liberal capitalism to generate the technological innovations necessary to prevent dangerous climate change. The case is made for the need for institutional evolution to drive the climate innovation, and the potential for climate innovation in an increasingly economically interconnected world.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Climate Innovation by N. Harrison, J. Mikler, N. Harrison,J. Mikler in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Environmental Economics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

An Introduction to Climate Innovation

The international negotiations for reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions conducted under the purview of the United Nations have garnered much attention, both in the press and in the scholarly literature. However, the results of these negotiations have delivered little and global GHG emissions continue to rise. After Copenhagen, it became clear to all but the most optimistic that an effective global political agreement to mitigate climate change is very unlikely. If the past is a guide to the future, it seems more likely than not that future international negotiations will also fail. This point is made by authors such as Giddens (2011: 208), who notes that hopes for an effective international agreement rest largely on ‘an illusory world community’. The efforts of the handful of nations that are the key GHG emitters are of particular importance, because whether or not negotiations succeed and an international agreement emerges, it will be their national governments that face the challenge of implementing policies to meet GHG emission reduction targets.

There is some cause for optimism in this respect. In the wake of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), Annex 1 countries agreed to bear the brunt of the huge GHG emission reductions required to prevent a dangerous change in the global climate, and most national governments have established ambitious targets.1 This is true even of the United States (US), which has failed to ratify the Kyoto Protocol but has recently proposed a non-binding target to reduce its emissions by 83 percent by 2050 (UNFCCC, 2011; Hassol, 2011). That is an essential but easy first step. What remains is to develop the means to meet those targets. Political constraints ensure that all governments – especially democratically elected ones – cannot significantly increase the economic costs of essential goods and services or sufficiently regulate social activities to meet their self-imposed or environmentally desirable GHG emissions reductions targets. Their preferred option will be to develop technological innovations to reduce GHG emissions – that is, technological innovation to mitigate climate change, what we call climate innovation.2 The importance of climate innovation to combat climate change is not new. From the earliest days of the international climate change negotiations, there has been a general acceptance that technological innovation will be crucial to mitigating climate change. It therefore seems increasingly inevitable that climate innovation will have to emerge in distinct national contexts. The attraction of the technological innovation option is that it supports government efforts to maintain economic growth. But what is the potential for climate innovation in countries that embrace the most liberal conceptions of capitalism such as the US? This is the puzzle we investigate in this book.

Climate innovation and the market

Technological innovation is generally believed to be a primary strength of capitalism. In a reflection of the prevailing zeitgeist and the mandate of the 1997 Kyoto Protocol to the UNFCCC, studies – for example, those of the IPCC, inter-governmental agencies and private consultancies – assume that the market will provide the necessary solutions.3 Rather than a comparative analysis that focuses on distinct national contexts, research into such questions has tended to produce generalizations for public policymakers that are increasingly being followed as received wisdom – for example, taxing emissions, subsidizing the uptake of new low-emitting technologies, introducing market based systems to trade emission rights, and so on. It is almost as if a ‘Washington Consensus’ for mitigating climate change has emerged, though in this case not from Washington. It is commonly assumed that if prices are made ‘right’ – that is, they include the cost of all externalities – all will be well. Therefore, it is now generally accepted by both economists and most governments that GHG emissions can be most efficiently mitigated – and technological innovations will spring forth that permit this – through market mechanisms. This is also true of much of the scholarly literature. For example, Newell (2008: 2) proposes a strategy for the US to generate technological innovations that would reduce GHG emissions based on the ‘simple principle that, within a market-based economy, success is maximized if policies directly address specific market problems’. His prescriptions are for government to ensure a stable long-term carbon price and fund targeted climate mitigation (primarily basic) research.

As such, the conventional wisdom is based on mainstream economic approaches that treat GHGs as an environmental externality of production to be internalized via market mechanisms. Altering market signals should ensure that environmental costs become economic ones, and in theory various positive and negative incentives, should permit governments to pressure consumers to choose GHG mitigating products. However, there are many reasons why such prescriptions may be valid in theory but not in practice. Because they are fundamental to the functioning of advanced economies, activities like transportation and energy production that contribute most to greenhouse gas emissions are price inelastic and not susceptible to market mechanisms. The deeply embedded nature of emissions in all aspects of economic activity underpinning advanced industrialized nations is widely recognized, yet the implications of this seem under-acknowledged in the embrace of a liberal, market perspective of the problem of climate change and mitigating its impact.

For example, the energy sector accounts for around 83 percent of greenhouse gas emissions (UNFCCC, no date),4 and a key component of the energy sector is transportation which on its own accounts for around 25 percent of total carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions. Up to 85 percent of this is accounted for by road transport (UNEP, 2003; Paterson, 2000). Given that around 75 percent of CO2 emissions over the lifecycle of any vehicle occur in use (Deutsche Bank, 2004: 58)5 taxing fuel to alter price signals may be a key policy for CO2 emissions of vehicles in use prior to encouraging the uptake of more efficient vehicles but would raise costs throughout the economy and may especially impact the poor. Even supply shocks such as the one in the latter half of the last decade when oil prices rose 300 percent between 2003 and 2008 (IEA, 2009) have had little impact on fossil fuel consumption. Indeed, a study by Small and Van Dender (2008: 182) concludes that ‘short-run supply shocks have bigger price effects and that longrun demand will not be curbed strongly as prices rise’. Other studies such as Graham and Glaister (2002, 2004) estimate that UK fuel prices would have to rise more than incomes to affect fuel purchasing decisions, and that even if one holds income constant a substantial 10 percent rise in the price of fuel produces only a 3 percent fall in fuel consumption. In the US around where 90 percent of travel is by motor vehicle, higher fuel prices only serve to increase costs to consumers who have little choice but to rely on their automobiles (OECD, 1996; Harrington and McConnell, 2003).

Data also suggest that even if this were not the case and policies to drive price signals for viable low carbon technology alternatives were more politically tractable, these may still have little effect for reasons beyond political and economic considerations. For example, in the EU the price differential between gasoline and diesel fuel is often seen as a key reason for the uptake of more efficient advanced diesel vehicles over the past decade to the extent that they now account for half of all new vehicle purchases. However, a snapshot of the gaso-line-diesel price differential in EU member states versus the share of diesel-powered vehicles demonstrates that there is little relationship between the two. For example, gasoline is over 50 percent more expensive than diesel in Austria, Belgium, Finland and the Netherlands, yet the share of diesels in total car sales in these countries varies substantially from 20 to 62 percent. Furthermore, although the percentage gasoline is more expensive than diesel fell from 44 to 37 percent on average across all EU countries over 2000–2006, the share of diesels in new car sales rose from 33 to 51 percent (OECD, 2007; ACEA, no date). In Japan there is a price differential of 46 percent, similar to that found in the EU, and it may be noted that this is a long standing feature of the Japanese market (OECD, 2007),6 yet virtually no diesel vehicles are sold there (JAMA, 2011).7 In the case of the US, even though diesel is marginally more expensive than gasoline, there would be little financial penalty in switching to diesel vehicles in terms of filling up a tank, while the cost benefits of switching to more fuel efficient diesel vehicles should have provided incentives to do so. As with Japan, this has long been the case but, as with Japan, it has not (United States Environment Protection Agency, 2010).8

There may be a range of reasons for consumers being unwilling to act ‘rationally’ on the basis of market price signals, such as US and Japanese consumers perceiving diesel vehicles as undesirable by comparison to gasoline powered vehicles with which they are more accustomed, while European consumers have long been more familiar with them and more inclined to consider purchasing them, regardless of sub-regional variations. But putting it simply, if consumers’ behavior reveals their underlying preferences, consumers in some European states are more inclined to buy diesels than others, while those in Japan and the US simply do not want to consider diesels regardless of the economic benefits. Putting it more technically, the normative basis for preferences, many of which are socially constructed, means that these can become institutionalized over time.

With such fundamental sectors as transport characterized by high price inelasticity of demand, the market mechanisms necessary to drive technological innovation for climate change are therefore either so politically challenging (for example, they involve very high taxation of emissions) or so politically infeasible (for example, they require high subsidies in a time of global economic challenges or direct regulation of consumer choice) as to make a reliance on them unwise. Climate change may originate from unrestrained capitalism, as Newell and Paterson (2010) argue, but a liberal preference for relying on the market and market mechanisms to fix the problem is dubious because it is not an artifact of market demand.

Market innovation versus climate innovation

Technological innovation in advanced industrial countries is the product of the iterative interaction of science possibilities with market demands, and is primarily the result of choices by profit-seeking firms. This model of technological innovation has been well accepted as appropriate and applied across a range of countries (for example, see Dosi, 1982; Freeman, 1992). In market economies, firms profit by meeting customers’ demands better than their competitors. For example, Apple is a profitable innovator because it has designed simple solutions to market needs using cutting-edge technologies, while the Toyota Prius, initially designed to demonstrate a technological solution to energy consumption, has created a niche market for hybrid fossil fuel/electric transportation systems.

Occasionally, science develops new knowledge that can drive the development of a whole new range of technologies, a new technoeconomic paradigm. For example, the transistor and integrated circuit made digitization of control systems possible and seeded the current Information Age. Beyond Apple iPhones, information management systems have profoundly changed production systems, marketing, and social relations. From information technology (IT) have sprung such varied systemic changes as the automation of custom manufacturing; increases in the energy efficiency of production systems; the Internet and World Wide Web; and simulations of building and automobile designs, nuclear explosions, and the effects of climate change. Whole new industries have emerged and old economy industrial companies have been replaced by entrepreneurial upstarts that earn billions from search engines and on-line advertising, a classic example of the ‘creative destruction’ of capitalism (Schumpeter, 1961[1942]).

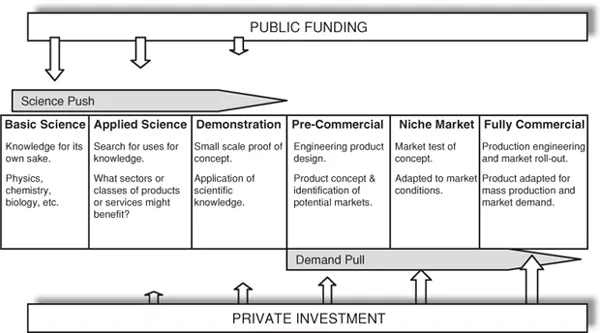

The conventional market innovation model reflects innovation from both demand-pull and from science-push. The distinction is only a matter of emphasis. Demand-pull suggests that market signals cause a search for technological solutions and science-push would also be ineffective if the new technologies that science produces were not better able to meet market demands than current technologies. We use information technology because word processor software on a computer is more flexible than typewriters, because digital technology is more readily adaptable than the analog technologies that preceded it, and because computing systems can render the complex mathematical calculations for simulations infinitely more rapidly than abacuses.9 In each case, the IT solution satisfies the primary consumer needs of document preparation and printing; cheap, flexible manufacturing; and system design and prediction better than the prior technology.

Markets and firms’ responses to their economic environment may explain the total amount of innovation but they do not explain the process of innovation or the activities that that process encompasses. If a firm sees within its market a threat or an opportunity which an innovation can curtail or seize, how does it develop that innovation and use it in the market? Early models of technological innovation presumed that the dominant cause was the push from scientific discovery, driven by government financing or the lone inventor is his garden shed (Bernal, 1989; Rosenberg, 1994; Bush, 1945). As new scientific knowledge is produced, eventually some entrepreneur or entrepreneurial entity finds a way to put it to use in satisfying human needs. Later theories argued that market demand determined technological innovation (Schmookler, 1966; Mowery and Rosenberg, 1979). Innovation is now recognized as a complex, iterative process with multiple internal positive and negative feedback loops that connects developments in scientific knowledge with market demand (Freeman, 1979; Keller, 2008).

Figure 1.1 is a simple, generalized model of the ‘normal’ market-driven innovation process. Firms in most industrial sectors will follow much the same steps in a process that translates scientific knowledge into products and services that meet consumer needs. However, although some commentators such as Grubb (2005), a leading scholar of climate change, and to some extent Pielke Jr (2010) apply much the same model as shown in Figure 1.1 to the process of innovation to address climate change, we contend that the innovation process shown in Figure 1.1 is not directly applicable to climate innovation. This is because the process for delivering technologies for climate innovation is different from the ‘normal’ process in three important ways: it demands inter-disciplinary research; it must meet technical targets rather than market demands; and, relatedly, consumers do not demand its effect, GHG reductions.

Figure 1.1 The market innovation process

First, regarding inter-disciplinary research, useful and necessary innovations may be found in every aspect of modern life from agriculture through construction to transportation and may involve technical knowledge and production techniques from several scientific disciplines and multiple industries. For example, reducing GHG emissions in transportation may involve research in materials, fossil fuel combustion, tire design, and chemistry. This means that the disciplinary silos in universities and industry specific research by firms are unlikely by themselves to be as successful as distributed innovation networks or custom constructed inter-disciplinary research facilities exemplified by Bell Labs in its heyday (Milford and Barker, 2008).

Second, to meet GHG emissions reductions targets, nations cannot rely on market demand. They must invest in the development and diffusion of a range of technologies that will reduce their emissions by a defined amount, about 80 percent by 2050 for the industrialized countries as a group (Hassol, 2011). Satisfying an environmental necessity is very different from satisfying the demands of human consumers. Consumers may demand goods and services that are cheaper, faster, smarter, and easier but the ‘only’ punishment for failure may be bankruptcy of a firm and loss of jobs. The environment is expected to be much less forgiving, if emissions reductions targets are not met.

Third, consumers do not demand technologies that are developed specifically to mitigate GHG emissions. Indeed it is unlikely that they ever will. They may demand technologies that improve their lives that also reduce their ‘carbon footprint’ but they do not expect to have to manage their footprint directly. They may select the most environmentally efficient products but do so as long as they satisfy other more important personal needs they have. This is suggested in surveys of social attitudes (for example, see Mikler, 2011),10 as well as in analyses of product development. For example, a recent study by Knittel (2011) shows that nearly all the advances in vehicle engine technologies since 1980 that could have gone into reducing CO2 emissions have gone instead towards heavier, more powerfu...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- List of Abbreviations

- Acknowledgments

- Notes on Contributors

- 1 An Introduction to Climate Innovation

- 2 Institutions that Influence Climate Innovation

- Part I: The National Context of Climate Innovation

- Part II: The Corporate Context of Climate Innovation

- Part III: Climate Innovation Across Borders

- Bibliography

- Index