eBook - ePub

Human Trafficking and Migrant Smuggling in Southeast Europe and Russia

Learning Criminal Entrepreneurship and Traditional Culture

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Human Trafficking and Migrant Smuggling in Southeast Europe and Russia

Learning Criminal Entrepreneurship and Traditional Culture

About this book

Through unprecedented access to over 100 court files and sentences, and interviews with police and security personnel in both origin and destination countries, this book provides the most comprehensive exploration to date of human trafficking and migrant smuggling in Eastern Europe and Russia.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Human Trafficking and Migrant Smuggling in Southeast Europe and Russia by Johan Leman,Stef Janssens in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Civil Rights in Law. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Networks: Rational and Cultural Components

1. An introduction

This book discusses the trafficking of human beings (THB) and smuggling of migrants (SoM) from and via Southeast Europe and Russia (SEE&R). In terms of arrival or transit countries, we shall limit the cases examined to Belgium. In some cases, however, practices in Germany, the Netherlands, France, Italy, Austria, Spain and the UK are discussed if they arise in the Belgian files. When we say ‘from’ Southeast Europe and Russia, we refer to networks from Albania, Romania and/or Bulgaria, but also from Russia. By ‘via’ Southeast Europe we refer to networks originating from Turkey, Iraq, India, Pakistan and China, when they cooperate with one or more SEE&R networks or travel through an Eastern European country.

The authors have focused their attention on international networks in which criminal organizations are involved. Using the criteria of the explicit involvement of criminal organizations and the Eastern Europe-to-Belgium link means that generalizing about THB and SoM either on a small scale or outside Europe is not within our remit. There are in fact many individual or ‘soloist’ traffickers at work, which are not the object of our study. Not all illegal transports of people across a border are, by definition, people smuggling. In order to qualify as people smuggling, there must be real illegal profits accumulated by the trafficker through the transport. Illegal border transports on humane grounds, in which only the operating costs are paid without any acquisition of real profits, do not therefore constitute people smuggling. In addition, a distinction must be made between people smuggling and illegal migration, which is generally not allied to criminality.

It is not the authors’ intention to suggest that all cases of SoM and THB from SEE&R conform to the patterns observed in this study. In limiting the subject to THB and SoM in SEE&R and further restricting it to only a few countries, even if those are very important in the context of this trade (Carletto et al., 2006; Hajdinjak, 2002; Limanowska, 2002; Monzini, 2001; Wallace et al., 1996; Kara, 2009), the authors acknowledge that their findings for THB and SoM as businesses should not be extrapolated to other continents and countries (McCabe, 2010). Still less is it their intention to claim that this business should be seen as a model for the overall current patterns of irregular migrations from Albania, Bulgaria, Romania or Russia to Western Europe, or for irregular migrations in general (see Gurak & Cases, 1992; Hirschman et al., 1999). Interpersonal factors may play a more significant role than organizations in most of the irregular migrations. Research indicates that when traffickers are recruiting, the social networks of acquaintances, family and person-to-person advertising are considered by the prospective migrants to be the most trusted factors (Boyd, 1989; Köser & Pinkerton, 2002: 22–24). However, from a legal point of view these people cannot be seen as conscious participants in the illegal construction.

Both authors have been involved in the fight against THB and SoM for many years. Johan Leman was involved for ten years in the fight against THB and SoM. He was director from 1993 to 2003 of the former federal Centre for Equal Opportunities and Opposition to Racism (CEOOR) that was the de facto national rapporteur for Belgium on THB and SoM. He was also a member of the task force against THB in Belgium (1995–2003). At the end of the 1990s, he had several meetings in Sofia with a former head of Intelligence and with some Bulgarian police officers. He is currently emeritus professor in social and cultural anthropology at KU Leuven University.

Stef Janssens serves as an expert analyst of THB and SoM and participates in the meetings of the national rapporteurs on THB of the European Commission. He cooperated in the preparation of the OSCE report (2010) on THB: ‘Analysing the Business Model of Trafficking in Human Beings – OSCE’. In 2014 he participated as an expert in the SELEX project (Severe Labour Exploitation) of the Fundamental Rights Agency of the European Commission. He served as an adviser to several Belgian parliamentary commissions on organized crime and human trafficking between 1996 and 2003. In his capacity as a THB and SoM expert, he also acted as a liaison for Belgium with the US embassy to comment on the TIP report by the US State Department. Both authors are associate members of LINC (Leuven Institute of Criminology) at KU Leuven. The authors both participated in a NATO advanced research workshop on ‘Human Trafficking, Smuggling and Illegal Immigration: International Management by Criminal Organizations’, where they were invited to present a paper on the topic (Sofia, 13–16 November 2007).

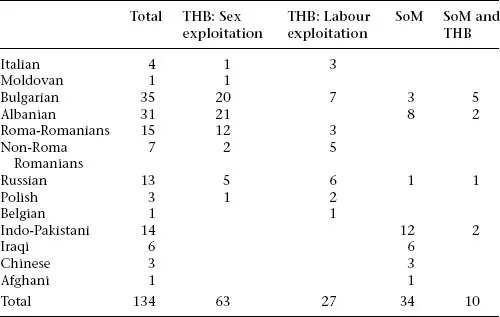

The cases we examined involved 63 files concerning sexual exploitation and 27 files concerning labour exploitation, in other words, 90 files relating to THB without any SoM involvement. A further 34 files involve SoM and in a further ten there is a mixture of SoM and THB. Thus, in fewer than one in ten cases do we find a confluence of the businesses of THB and SoM; furthermore, we find that it is in these cases that mafias or mafia-like organizations are at work. Most of the files relate to only one aspect, either SoM or THB (see Table 1.1). Together they represent 53 mostly large-scale networks.

Therefore it is generally the case in the SEE&R files that the entrepreneurs involved in SoM are different from those involved in THB, and both are different from the ones who invest in a mixture of the two. There seems to be some level of specialization, but the police and court files indicate that what the organizations and criminal activities have in common is their maintenance of two fundamental components: a business-like, rational organization culture, combined with à la carte use of fragments or manipulated fragments of traditional culture. In the period since 1994 a third aspect has emerged: a capacity for proactive learning. What characterizes the networks is their rationality; their ambivalent relationship with traditional cultural practices – sometimes strongly authentic, for example where it concerns money laundering by the entrepreneurs, and sometimes very manipulative, for example where it concerns the control of subordinates; and finally their learning capacity.

Table 1.1 Distribution of cases (in files) across nationalities and types of business

Throughout most of the files it appears we are faced with three distinct worlds and practices: the world of the entrepreneur; the world of those who make use of that business; and, in between, the world of the middlemen. Each has its own project, its own dynamics and its specific way of dealing with the cultural background. Among the dossiers on people smuggling, we find in 2015 an increased blurring between the world of the entrepreneurs and that of the middlemen. It seems that with respect to people smuggling, there are now various smuggling networks that cooperate in a flexible way with each other. The reason for this lies in the importance of territorial specialization and flexible cooperation throughout the extended international traffic routes. The middlemen who operate in this terrain, especially those in the transit areas, are gaining in importance.

An entrepreneur also follows the normal rules of entrepreneurship such as exist in the world of legality as much as possible. The measures he takes are based on rational considerations. How he handles traditional culture is similarly inspired as well. The efficient entrepreneur seeking to succeed in business is someone who wishes to learn as much as possible, from his own errors as well as from what his partners with whom he has agreements are doing. He seeks to run as close as possible to the world of legality in an attempt to keep his own risk as low as possible.

Those who make use of the business have, in turn, their own project: to be successful in their plan to migrate (in the case of SoM) or to generate an income (in the case of THB). However, it must be stated that in some cases we really do need to speak of victimization, although this usually involves an unreasonably low level of participation in the profit of the entrepreneur. Moreover, because of their dependency with respect to the exploiter, the possible victim generally finds themself suffering from poor working and living conditions. Culture of origin plays a role to the extent that the consumer allows themself to be intimidated when the entrepreneur or the middleman makes use of it.

At the level where the middlemen (or -women) are involved, the logic of control plays a rather more prominent role. Middlemen take on the responsibility of safeguarding the dependent relationships by which the victims or users of the business remain under control. In the people-smuggling networks, the control aspect continues to play a role, but the trafficker is often just a flexible local entrepreneur who specializes in the trafficking routes within their territory and knows how to move within those confines. The traditional culture is much used, but it is frequently combined with physical or mental violence as well, especially in situations beyond the bounds of the legal world. Often the middleman is the one most exposed to risks, from competing with similar characters who work for other entrepreneurs or due to his or her vulnerability to police activities.

The entrepreneur is the one who moves around at the level of society. He/she has to try to exploit the structural dysfunctions and the corruptibility of the staff who are working within the legal structures. At the same time, he/she has to try to ‘legalize’ the financial benefits of his entrepreneurship in the legal circuit. The subculture of the criminal middleman functions at the level below him/her, ensuring simultaneously a connection to the customers who make use of his/her services. As mentioned above, in the case of SoM the boundary recently has begun to soften between the world of the entrepreneur and that of the middlemen. Those making use of the business from each side have their own projects and agency. Besides the agency of every player, each at their own level, where especially the entrepreneur and the consumer in the case of SoM draw on rational considerations, fragments of traditional culture appear to be the glue between the different processes, especially in the world of these middlemen who operate in the country of destination. Furthermore, the business has been evolving at the level of the entrepreneur over recent years, especially on the basis of learning processes. It remains to be seen whether the same will soon be true at the level of the middlemen in the transit countries as well.

It is very likely that the fact that the analyses and insights are based on police and court files explains why the authors fundamentally see a rational strategy in the business. The authors look at the criminal business as motivated by economic pay-offs in the minds of the entrepreneurs. Of course, this is not to say that some actors in the business may be less rationally inspired. The authors are aware that the rational choice bias may be due to the nature of the bureaucratic organization of the files they studied. We are well aware that drawing from police and court files has its limitations. We also acknowledge that it is possible to debate whether the police and court context is the right one in which to discuss THB and SoM at an academic level. However, the material is nonetheless exceptional because it has a highly varied and thorough empirical basis, albeit biased by police work. It is qualitatively rich material and also, because of its quantity, representative. In addition, the information presented by the authors is also based on annually published statistical data and on their interviews with magistrates, lawyers, labour inspectors and policemen within the framework of an annual report on trafficking in human beings. In particular, it reveals a development in the entrepreneurship and in the use of traditional culture on the basis of material collated in a similar manner spread over a period of 20 years. That development constitutes the core topic of the book.

Our hypothesis is that the presence of rationality in entrepreneurship is fundamental to understanding its proactive learning dimension, which will be one of the major insights of the study. Moreover, the use of traditional culture increasingly becomes an option within the perspective of rationality.

A final point that deserves attention at the end of this introduction relates to our approach to some definitions. We are aware that some preliminary options and notions should be clarified from the beginning. One of these questions is, what are the criteria for describing a certain business activity as THB or SoM? According to the United Nations Protocol, ‘Smuggling of migrants shall mean the procurement, in order to obtain, directly or indirectly, a financial or other material benefit, of the illegal entry of a person into a State Party of which the person is not a national or permanent resident’ (UN, 2000b). According to the United Nations Protocol definition, the activity becomes trafficking if there is exploitation, including sexual exploitation, forced labour or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removal of organs (UN, 2000a). Several studies have correctly shown, however, that SoM can easily degenerate into THB (Meese et al., 1998, cited in Salt, 2000: 22; Cameron, 2008; Kyle & Koslowski, 2011; Quaeson & Arhin, 2012).

The files will show that in some cases there may be grey areas between SoM and THB entrepreneurship, and between THB and illegal work in migration (cf. Aronowitz, 2009; Papanicolaou, 2011). This corresponds with the finding of the Europol Organised Crime Threat Assessment (OCTA) Report: ‘In the often extended time between stages, transiting migrants are frequently exploited in illicit labour, thus marking a point of contact between illegal immigration and trafficking in human beings (THB)’ (Europol, 2011: 22). Another very important difference between THB and SoM is that ‘trafficking does not require transportation (across borders) and under this definition, persons may be victims of trafficking within their own countries’ (Aronowitz et al., 2010: 17). However, borders are in fact crossed in most of the human trafficking cases discussed in our book.

The starting point for this study is the existing legislation. This may be the subject of debate. Because the Belgian Human Trafficking Act is defined in terms similar to those in the UN Protocols, the most obvious option, in our view, in a study that originates from police and court files is to follow the same qualifications as used in these files. For example, in terms of Belgian law, labour exploitation in relation to human trafficking is defined in a much broader sense than the term ‘forced labour’, which is based on compulsion in the strictest sense. The Belgian Human Trafficking Act refers to working below the level of human dignity. It makes use of a confidential indicators list, and it makes reference to a severe underpayment of deductions, poor housing conditions, threats and so on. To risk a condemnation for THB, one indicator is not enough; a combination of all these indicators is needed. The Belgian Act does not take account of whether the victims are acting voluntarily, or of whether they regard themselves as victims of THB. The Belgian THB legislation also prescribes that Belgian citizens may become victims of THB, as in some loverboy cases. In such cases, no link would be made with the migration issue.

Another related question is whether sex work, under certain conditions, really presupposes that the person undertaking the activity must feel that he/she is being treated inhumanely. The authors agree that the victim’s perspective has to be examined in each case for its real content. Is ‘victim’ always the right word? In certain cases, the word ‘victim’ is appropriate, in other cases not. However, one should not forget that there are frequently ill-advised risks associated with SoM and THB that could really endanger people’s lives, and death is not unusual in some SoM cases.

Yet another question concerns the relation between SoM and illegal migration. SoM is the criminal business that develops and expands on the wish of candidate migrants to migrate illegally. The United Nations has condemned people smuggling as a criminal activity. Within the wider context of illegal migration, people smuggling is only one component, albeit an important and criminal one. Beyond that there is again a grey area.

We are aware that a debate can be justifiably opened on the adequacy – or, as the case may be, inadequacy – of legal descriptions of THB and SoM activities, just as a discussion can be initiated about the validity of victimization as instanced in many sex work situations. We know that where definitions and figures are concerned, there is an ongoing debate in the US, and rightly so. As far as the definitions of the United Nations are concerned, we would like to point out that these have been successfully applied, on the ground, all over the world by various international agencies such as Eurojust, Europol, ILO, OSCE and IOM. The most important stakeholders for a successful policy on trafficking in human beings, of which the Belgian model is one of the leaders in international terms, are the specialized shelters for victims of trafficking in human beings; the specialized reference magistrates dealing with trafficking in human beings; the specialized trafficking in human beings units within the police forces; and the labour inspectors – which is therefore quite different from a migration policy in which immigration laws are the approach used. We should nevertheless point out that the Belgian jurisdiction in these matters is not at all strict or repressive, and that in many cases it is female police officers and female judges who are dealing with the possible cases of victimization in sex work. Sex work in Belgium is, for that matter, a practice that is not subject to repressive action.

We have had many contacts with the actors in the field, such as magistrates, policemen, labour inspectors and victim centres. In addition, we have always checked the files involved for mention of criminality, finding clear and unambiguous evidence to affirm its role. Our study does not aim to contribute to that specific debate, but rather to focus on the position of traditional culture, rationality and learning processes. Despite its flaws, the material that we use and that the stakeholders take seriously allows us to acquire some insight into the developments in rationality and the position of traditional culture within the business from SEE&R.

The dossiers studied by the authors do represent unambiguously the role of criminal activity and do not simply offer the story of the organization of illegal migrations. They are clearly related to activities which, even with the necessary social contextualization and cultural reinterpretation from the point of view of the culture of origin, must be regarded as the product of criminal entrepreneurship. Very often it involves criminal organizations that are implicated not only in SoM but also in other criminal activities, such as drugs trafficking.

A final question concerns the basis on which a business activity may be called mala fide or bona fide. Europol in its OCTA Report from 2011 reported an ‘increasing proximity between organised crime groups and legitimate business structures’ (Europol, 2011: 29). In discussing entrepreneurship in this criminal business, in some places we make a distinction between mala fide and bona fide entrepreneurship. We use a broa...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- 1. Networks: Rational and Cultural Components

- 2. Leadership and Structures

- 3. Making the Business Operational

- 4. Increasing Benefits, Decreasing Risks: The Impact of Learning

- 5. ‘Money, Money, Money … Always Sunny!’

- 6. Rational and Cultural: Conclusions and Policy Proposals

- Afterword

- References

- Index