![]()

1

The Roots of Central Banking

In a short and lucid essay Kenneth Boulding addressed the question of the substantive – even more than the legal – legitimation of the institutions called upon, like the central bank, to pursue specific general interests.1 He classified the sources of legitimacy into six categories: “payoffs” (the service rendered by the institution), “sacrifice”, “age”, “mystery”, “ritual or artificial order”, and “alliances”.

A reflection on central banking, on its role in the economy, on the ways in which, among difficulties and misunderstandings, that role is interpreted – thus on the service rendered, the primary source of legitimation – must link history, theory and practice, including recent practice, to proposals for reform. It must focus on the economic and legal heart of the central bank institution: the discretion in the performance of its tasks and the independence that is the precondition of that discretion.

To a varying degree the central bank was recognized as having independence and hence administrative and technical discretion2 to enable it to contribute to the performance of the economy via the functionality of money and finance. The special nature of the service central banks are required to supply and the advantage they enjoy in providing it compared with other institutions lie in their discretionary ability to use both administrative and market instruments promptly and without any budgetary constraints. Central banks can act immediately. They are free from the passage of legislation through Parliament and from the complexities of administrative procedure, the slowness of the bureaucracy. They have full control over their main resource: the banknotes they issue under the conditions of monopoly granted by law. Accordingly, they regulate the “monetary base” or “high-powered money” – in addition to the banknotes in circulation, the deposits that banks must or want to hold with the central bank – on which the market bases all the monetary, credit and financial activities in the economy.

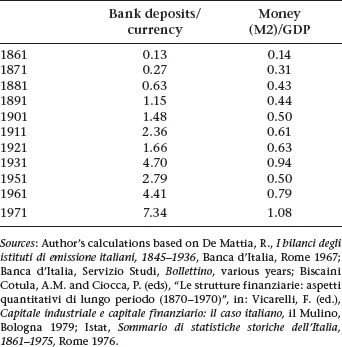

Money – a public good3 – is today fiat or bank money, no longer a piece of metal, minted by the sovereign. It consists of the banknotes issued by the central bank and above all of the deposits that the public holds with the banks, equal to a multiple of those that the banks hold in monetary base as a liquidity reserve at the central bank. The Italian case can illustrate the point, Italy being, financially, neither a first-comer nor a late-comer (Table 1.1).

The multiplication of bank deposits – and loans – derives from the fact that the excess reserves lent by a bank to its customers remain within the banking system. Through the flow of collections and payments and debit-credit relationships in the economy they are transferred from one bank to another. Each bank keeps a part against the new deposits that it takes and lends the remainder, giving rise to a total stock of deposit-money equal to several times the monetary base created by the central bank.4

Table 1.1 Monetary ratios in Italy (1861–1971)

In a capitalist market economy the fundamental raison d’être of the modern central bank is to provide a barrier against the instability inherent in the mode of production that has spread across the world in the last three centuries.

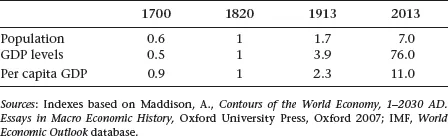

This economic system multiplied more than tenfold the average real income per capita of the inhabitants of the world, after it had tended to stagnate for thousands of years. This simple fact – the ability to develop production and increase the material wellbeing of a world population that has grown from one billion in 1820 to seven billion today – explains the system’s success and its spread even to the countries historically, culturally, institutionally and politically least inclined to adopt it, such as China (Table 1.2).

At the same time the system has proved to be unfair in the distribution of income and wealth, and also polluting and harmful to the environment, since private producers generate negative externalities. What is most important for the purposes of this work is that the system has proved to be highly unstable. Large upward and downward swings of the prices of consumer goods, of the values of assets (shares, buildings, bonds, claims), and of exchange rates, major recessions of investment, production and employment, and strings of bankruptcies of banks and other financial intermediaries have dotted the history of the capitalist market economies. These have given rise to acute tensions and suffering variously distributed within the social body, with serious repercussions that have also been political and institutional.

Table 1.2 World population, GDP levels and per capita GDP (1990 Geary-Khamis dollars) (1820 = 1)

In terms of instability, the system has generated:

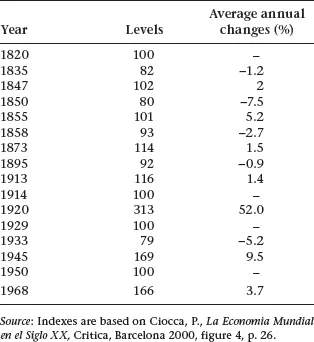

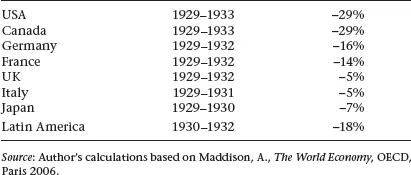

•consumer goods price inflation in industrial countries at up to double-digit annual rates – during the last part of the 18th century and the Napoleonic Wars, from 1895 to the end of the First World War, and from the middle of the 1930s to the 1980s – that when it became hyperinflation destroyed the real value of money and credit; consumer goods price deflation, on average in the industrial countries between 1821 and 1850 and then, at an annual rate of 1–2 per cent, during the Long Depression of 1874–1896 and at three times that rate from 1927 to 1933, the period that saw the authentic Great Depression, commonly referred to as the crisis of 1929 (Table 1.3);

•frequent contractions of economic activity in individual countries, with world output falling short of its trend value by 8 per cent in 1835 and 1853, 4 per cent in 1870 and 12 per cent in 1929–33. The 1929 recession was the worst, with GDP contracting by 29 per cent in the United States, 18 per cent in Latin America and 9 per cent in Europe (Table 1.4). In 1932 world GDP was 17 per cent below its level in 1929;

Table 1.3 Consumer prices in industrial countries (1820–1968)

•unemployment that was persistently more than 10 per cent of the labour force, with peaks of 25 per cent in the United States and Germany in the early 1930s;

•the collapse of share prices on the stock exchange on several occasions – 1895, 1907, 1929, 1937, 1940, 1987, 2001–2002, 2008 among others – to the point of securities losing 80–90 per cent of their nominal value and nearly 50 per cent of their real value;

•current and capital account losses by banks and other financial intermediaries that in some economies amounted to tens of percentage points of GDP in a single year.5

Limiting instability is therefore crucial to the management of a capitalist market economy, to ensure its survival.

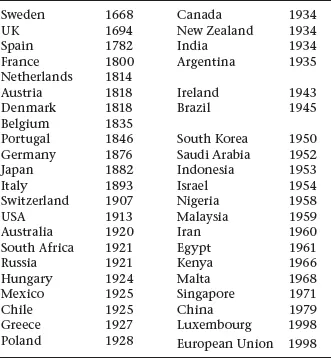

Today’s central banks have evolved over three centuries of events, debates and time scales that differ from country to country. They have in common the gap between the present arrangements and the original reasons that drove the founders of the “banks of issue”, the precursors of modern central banks.6 States gave up the privilege of issuing money to these institutions, private or public banking intermediaries. The aims varied: to receive financial support, to centralize the nation’s metallic reserves, to restore value to the currency, to rationalize the payment system, to duck out of a delicate responsibility by blaming the intermediary for any errors in the difficult management of the currency. As time passed, being the government’s banker and depositary of the power of issue, over and above what the State itself had intended, allowed the institutions that had sprung up, mainly in the 19th century, after the prototypes of the 17th century in Sweden (Riksbank) and England (Bank of England),7 “to develop their particular art of discretionary monetary management and overall support and responsibility for the health of the banking system at large”. 8 France equipped itself with a bank of issue in 1800, Austria and Denmark in 1818, Belgium in 1850, Japan in 1882, the United States with the Federal Reserve in 1913. The Bank of Italy was created in 1893, sharing the power of issue with Banco di Napoli and Banco di Sicilia until 1926, when it became the monopoly issuer (Table 1.5).

Table 1.4 Contraction of real GDP from peak to trough (1929–1933)

As long as the metallic standard was in force, monetary management was based on the defence of the public’s ability to convert, at a predetermined price, banknotes into metal (gold, under the gold standard, or silver, or gold and silver together under bimetallism) and vice-versa. Convertibility ensured the acceptance of banknotes by the public, thereby making the supply of money consistent with the demand for money coming from the economy. The total quantity of money varied with the central bank’s metal reserves, to which the amount of banknotes issued was linked. Within limits, the central bank could respond to losses or excessive increases of metal reserves by raising/lowering interest rates so as to stabilize the total quantity of money (metal plus notes) and therefore, it was believed, the average level of the prices of goods and services.9 In the era of metallic regimes, from the close of the 18th century to 1913, prices were stable in the very long term. In the main European countries in 1913 they were close to their levels a century earlier. Nonetheless decades-long periods of inflation and deflation alternated during the century.

In addition, the possibility of issuing banknotes required a “bank of the banks” to provide liquidity to the entire financial industry if it was needed. This task could not be independent of a special concern for the balance sheet solidity of the intermediaries to be financed, which nonetheless often competed in the market with the banks of issue. The latter were called upon to lend money, in increasing amounts and with increasing frequency, to the banks that were temporarily without, by discounting bills, buying bonds, granting advances against securities and other forms of “lending of last resort”.

Table 1.5 Foundation dates of central banks

Apart from the periods of recession, as economic activity expanded, the demand for money tended to grow faster than the stock of metals for monetary uses. The increase in the quantity of banknotes and bank deposits serving as means of payment and store of value for prudential or speculative purposes therefore placed on the banks of issue the task of shoring up currencies whose use could less and less be imposed by law and which were more and more “fiat” money.

The 20th century saw a succession of regimes different from the metal standard: the gold-exchange standard, the dollar standard, currency areas with more or less fixed exchange rates, and various forms of floating exchange rates. It also saw pronounced imbalances caused by price inflation and deflation, bank failures and plunging stock exchanges, contractions of economic activity and unemployment.10 The abandonment of the classic metallic standard, which was based on the Bank of England and the City of London as the world’s financial centre, gave the banks of issue greater freedom in their manag...