eBook - ePub

Mapping Mass Mobilization

Understanding Revolutionary Moments in Argentina and Ukraine

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Through a paired comparison of two moments of mass mobilization, in Ukraine and Argentina, focusing on the role of different actors involved, this text maps out a multi-layered sequence of events leading up to mass mobilization.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Mapping Mass Mobilization by O. Onuch in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Comparative Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction: The Shock and Awe of Moments of Mass Mobilization

I could barely believe my eyes, there were hundreds of thousands, millions.

(Yuriy Polyukhovych, Activist; yellow Pora,

Kyiv Coordinator)

Kyiv Coordinator)

Introduction

Moments of mass mobilization, like those in Argentina (2001) and Ukraine (2004), tend to catch governments and analysts by surprise. These are moments when millions of previously disengaged ‘ordinary’ citizens1 join activists in protests en masse, making regime change likely and systemic (social, economic or political) transformation possible. First the media, then social scientists, scramble to understand and explain the presence of ‘ordinary’ citizens, who left their private homes and entered the political arena. In recent years, we have witnessed several moments of mass mobilization and yet we still struggle to understand them. Be it in Argentina in 2001, Greece in 2007, Egypt in 2011, Turkey in 2013 or Ukraine in 2004 (or more recently in 2013), we watch as the sea of ‘ordinary’ citizens and activists floods the streets, filling up every nook and cranny of large cities and seemingly pushing aside all conventional and status quo politics in one swift swoop. We are astounded by their political courage and determination, and thus we marvel at the profound moment as it unfolds. Such exceptional moments astound us, not least because accepted theories in political science, such as those by Lichbach (2004), Muller and Opp (1986), Opp (2009), Popkin (1979), would have us believe in ‘collective action problems’ and ‘free rider’ incentives. Puzzled, we ask ourselves: How can we explain this mass mobilization?

This question is difficult to answer because mass mobilization seems to come out of nowhere, and it fades away seemingly just as fast. Mass mobilization is also difficult to map because it is likely preceded by and followed by mostly activist protests. Thus, allow me to take a quick detour to better define mass mobilization. Such mass protests tend to be not only proportionally larger than other protest events (where a substantial proportion of the population are taking part in the protests, usually 100,000–250,000 people) but also tend to share three distinct characteristics. First, the balance of participation shifts away from activists, opposition members/organizations and students to a new protest majority made of ‘ordinary’ citizens. To borrow language from electoral behaviour literature, one could say that these are protests when ‘ordinary’ citizens become the ‘median protester’. Second, in cases of mass mobilization, ‘ordinary’ citizens tend also to form cross-class and cross-cleavage coalition. People with different political preferences are united momentarily in protest. Third, these protests are more extemporaneous; that is, they are in part undirected and lack a clear leadership (at least at first). Put otherwise, activists and opposition politicians lose control over the protests (even if only for a short period) when ‘ordinary’ citizens join in en masse.

Due to our inability to grasp these rare instances of political defiance, the word ‘revolution’ is often used to describe the protest events. While in some cases mass mobilization has helped in bringing down a regime, the protests themselves are not ‘revolutions’ per se. The term creates expectations of systemic change that may not be possible or even sought by the protesters. Perhaps these extraordinary protests are simply, as Charles Tilly wrote, only ‘revolutionary’ situations or moments,2 when the mass mobilization in the streets creates the potential for systemic and/or regime change, but does not make ‘revolution’ a certainty. Thus, these are brief periods in time, when ‘ordinary’ citizens and activists have the opportunity to become the main players in politics, a game otherwise reserved for elite and formal institutional actors. Through such extra-institutional political participation, ‘ordinary’ citizens and activists can potentially push their countries to democratize (or to further democratize). But at the same time, these are moments when the regime can decide to retrench, to use even more repression, and even backslide away from any democratic achievements of the past. This engagement is especially interesting in democratizing contexts, such as in the cases of Argentina (2001) and Ukraine (2004), when citizens are still learning the ‘rules of the democratic game’ and when the risks of joining in are potentially higher than in established democracies.

Analyses by journalists and political scientists have tended to focus on several things: Sudden material deprivation which is understood to cause an angry and emotional response; the apolitical spontaneity of ‘the crowd’s’ actions; or, discounting their participation wholeheartedly, on the co-optation of ‘the masses’ by other political forces, be they national (politicians) or international (foreign governments, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and think tanks, and intergovernmental organizations (IGOs)). Accordingly, when ‘ordinary’ citizens protest, this is seen as wholly spontaneous and emotional, or co-opted and contrived by exogenous or local political forces.

Two trends have emerged in the analysis of mass mobilization, specifically in Eastern Europe (EE) and Latin America (LA), and more recently in Southern Europe and the Middle East and North Africa, that focus on the economics of protest rather than the politics of participation. The first trend identifies economic crisis and deprivation as explanatory causes of protest, and the second places emphasis on western IGO and NGO funds in ‘creating’ or ‘diffusing’ activism. Two best-case examples of these trends are the analyses of mass protest in Ukraine in 2004 and in Argentina in 2001. In Ukraine, foreign financing that sponsored, facilitated or diffused activist protests, and helped engineer an ‘electoral revolution’, is seen as the crucial explanatory factor of the 22–30 November 2004 mass mobilization (Åslund and McFaul 2006, 152, 97). In Argentina, the economic crisis, specifically the corralito policy, has been identified as the motivating factor behind mass mobilization on 19 and 20 December 2001 (Fiorucci and Klein 2004, Giarraca and Teubal 2004). Furthermore, initial studies of recent Egyptian and Greek protests also bear similarities to these trends (Bhuiyan 2011, Bratsis 2010). Following this logic, economic crises have produced many predictions of mass mobilization in Latin America, Eastern Europe and North America, and targeted foreign financing has left us expecting ‘revolutions’ in Belarus, Russia and Iran. Unfortunately, such structurally focused analyses failed to note that although there is multiple and ongoing deprivation causing economic crises, and continuous attempts at the financing and diffusion of ‘electoral revolutions’, there are actually very few instances of mass mobilization. The empirical reality does not meet our expectations, and thus, when we do witness these extreme protest events, the puzzle continues to haunt us: How can we explain this mass mobilization?

A ‘revolutionary moment’ in Argentina, December 2001

From 1999 to 2001, President Fernando de la Rúa’s3 government was plagued by ongoing political and economic meltdown in Argentina. While it is true that de la Rúa inherited the majority of Argentina’s politico-economic woes from his predecessor President Carlos Menem, these problems were exacerbated by his administration’s poor governance and mismanagement. The country’s economic problems included rising public debt, double-digit unemployment, mass capital flight and industrial bankruptcy. Politically, there was the problem of widespread systemic corruption coupled with a growing crisis of representation and legitimacy. In 2000 the notorious Senatorial bribes scandal implicated high-ranking members of the Alianza4 government and triggered the resignation of the popular Vice President Carlos Álvarez.5 And with his departure, the unstable governing coalition began to crumble. In October 2001, 25 per cent of the ballots cast in the Congressional elections were purposely spoiled or marked incorrectly in protest at the lack of real political options for the electorate. Thus, by November 2001 Argentina was in the midst of its worst politico-economic crisis since its transition to democracy in 1983, and it was ‘ordinary’ Argentines who were increasingly feeling the brunt of these hardships. When in late November 2001 Argentine banks reported account draining, President de la Rúa and his then Finance Minister Domingo Cavallo6 began implementing emergency measures to stop capital flight and prevent complete economic collapse. On 1 December the corralito (play-pen) policy was announced (‘Cavallo Analiza Dolarizar Los Plazos Fijos En Pesos’ 2001). With this policy, all dollar accounts were frozen and Argentines were only permitted to withdraw ARS 250 per week (at the time equivalent to USD 250). Within days, small groups were protesting outside the banks demanding withdrawal of their savings. On 16 December food riots and lootings broke out in poorer working-class neighbourhoods in Rosario and Córdoba and later spread to the suburbs of Gran Buenos Aires.7 Between 14 and18 December, independent unions, Piquetero8 Social Movement Organizations (SMOs) and ‘leftist’ activists intensified their coordination of large protests, already underway since August 2001, and expanded them to the Capital Federal (Buenos Aires City).9 At 21:45, on 19 December, embattled President de la Rúa declared a ‘state of siege’ via live televised address, banning all public gatherings and introducing a national curfew. When the announcement was made, several activist groups were already congregated in local squares and neighbourhood intersections. Although cacerolazos (‘pot/pan banging’ protests) were used throughout the year as a signal to politicians that the people were dissatisfied with their policies, on the evening of 19 December there was a citywide cacerolazo. ‘Ordinary’ citizens, still wearing their slippers and housecoats, gathered their children and dogs and began to march with their neighbours to the city centre. There was the ‘revolutionary moment’, the moment of mass mobilization, when ‘ordinary’ Argentines from different socio-economic backgrounds united in the city streets. The largest group congregated in front of the Casa Rosada (presidential palace) in the historical Plaza de Mayo (May Square), while others assembled in front of the Congreso (Congress) and a smaller group in front of Cavallo’s private home. The main slogans used were ‘¡Que se vayan todos!’ (‘May they all go’ or ‘throw them all out’) ‘¡Piquete y cacerola, la lucha es una sola!’ (‘Picket and pot, the struggle/ fight is one’) (‘Piquete y Cacerola, La Lucha Es Una Sola’ 2002). After midnight the Argentine National Gendarmerie came into the Plaza de Mayo to disperse the protestors. There were some violent clashes with militants but the bulk of ‘ordinary’ citizens had already gone home. Students, militants, journalists, independent union members and piquetero leaders stayed in the plaza and congreso and were joined by more activists the following day. On 20 December, ‘ordinary’ citizens stayed mostly in their neighbourhoods, but they continued banging pots/pans and began organizing local grassroots groups, which came to be known as asambleas (neighbourhood assemblies). As protests continued to intensify, and turned violent, de la Rúa announced his resignation and fled from the presidential palace in a helicopter. In the span of four weeks, Argentina saw a total of five presidents (Fernando de la Rúa, Ramón Puerta, Adolfo Rodríguez Saá, Eduardo Camaño and Eduardo Duhald). The protests continued but were increasingly coordinated by party, opposition and activist groups and by local neighbourhood assemblies. By mid-January locally organized co-operatives and assemblies began to expand and merge under umbrella organizations (asambleas populares – popular assemblies) coordinated by leftist party militants10 and other activist groups and unions. The protests persisted throughout January and February and although the mobilization began to fragment in March, frequent but much smaller protest events by specific groups continued into August 2002.

How has the 2001 mass mobilization in Argentina been analysed?

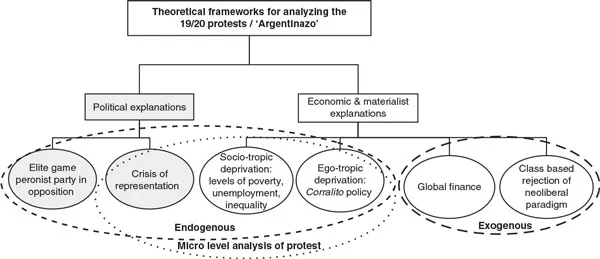

The December ‘19/20’ mass mobilization, or ‘Argentinazo’ as it is called by leftist parties and SMOs (implying a revolutionary nature of the protests), was a multifaceted, multi-actor, multi-event phenomenon. While each group of actors who participated in the events remembers this ‘moment’ differently, their own recollections are plagued with contradictions. Analyses to date have focused more often on economic and material variables and have been less able to fuse the economic and political explanations, presenting variations of the two themes. The explanations can be divided between those that focus on endogenous or exogenous contextual variables, which resulted in political economic crisis, which in turn produced the socio-tropic or ego-tropic socio-economic dissatisfaction or deprivation, which triggered a protest response (see Figure 1.1).

The economic argument has dominated most media11 and economists’ accounts. Some have even called the 19/20 ‘regime collapse’ and the 2001–2002 crisis the ‘Latino Americanization’ of Argentina – the moment when a once prosperous country, seeing itself more akin to ‘European’ Spain than ‘Latin American’ Bolivia, became as poor and as economically and politically unstable as the majority of its neighbours on the continent (‘La Latinoamericanización de Argentina’ n.d.). Although social scientists such as Mahon and Corrales (2002) and Rodrik (2003, 2006) agree that local politicians are in some way responsible for the economic demise, their explanatory focus has rested on macroeconomic variables. Stiglitz (2003) argued that the International Monetary Fund Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs), coupled with the fixed exchange rate of the Convertibility Plan, promoted a cycle of devaluation and raised the probability of capital flight and debt default. Together they have argued that these macroeconomic policies increased local unemployment and poverty rates, and thus heightened social stratification and socio-tropic deprivation in Argentina. This deprivation is understood to have first mobilized the suburban poor from the industrial ‘interior’ of the country in the late 1990s and then, in December 2001, the urban middle class. These explanations that focus on exogenously driven macroeconomic policy, as a cause of crisis, as well as protest response to said crisis, still leave us asking why did ‘ordinary’ people wait so long to join in? What about the economic fallout that triggered the mass mobilization, and why only on 19 December? Furthermore, why did protests shrink in 2002, when new macroeconomic restructuring produced even harsher economic realities? Thus, what role did exogenous macroeconomic policies play in the mobilization process?

Figure 1.1 Most typical analyses of 19/20 mass mobilization

A further neo-Marxist and Gramscian variation on the above, like that presented by Armony and Armony (2005) and Cheresky (2002a, 2002b), focuses on the broader problematique of the exogenously driven neo-liberal policies of the 1990s and the compounding social exclusion and loss of dignity they produced. Placing their focus on the class-based ‘social’ roots of the protests, Armony and Schamis (2003) have framed the crisis and the mass protest response, as the collapse of the neo-liberalist paradigm in Argentina. Alas, this class-based analysis does not adequately explain the cross-class and cross-cleavage nature of the 19 December protests. It is still not clear how and why different sectors of society, which arguably would have been affected to differing degrees by various economic policies, were mobilized simultaneously in the span of a few hours. Thus again we ask, what role did exogenous macroeconomic policies play in the mobilization process?

A separate group of political scientists and sociologists, including Auyero (2006, 2007), Delamata (2004), Levitsky and Murillo (2003), Svampa and Pereyra (2009), have given more focus to microeconomic causes of crisis. They have placed differing levels of emphasis on growing social stratification, inequality, unemployment and poverty as mobilizing variables. The focus here is more on ego-tropic dissatisfaction and deprivation. These authors agree that one or a combination of these economic variables mobilized the suburban poor and workers. But the ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures, Tables, and Maps

- Acknowledgements

- About the Author

- List of Abbreviations

- Maps

- Part I

- Part II

- Part III

- Part IV

- Appendices

- Notes

- References

- Index