![]()

Part I

Who Are the Returnees?

![]()

1

Introduction: Chinese Returnees in Context

The coming age of global talent circulation

In reviewing globalization, David Held et al. (1999: 283) state that “one form of globalization is more ubiquitous than any other—human migration.” Globalization leads to the transfer of new skills, knowledge, ideas and capital across national boundaries, particularly the increased international mobility of talented and highly qualified individuals. Talent circulation, which is more widely referred to as brain circulation, is the term generically used to describe movement of highly skilled immigrants who live and work in a foreign country for a certain length of time before returning home or moving to another foreign country.

One general trend in this aspect of globalization is the so-called “brain drain,” which refers to the flow of skilled professionals from developing countries to developed countries. This term was first coined by the British Royal Society to describe the outflow of scientists and technical workers to North America in the 1950s and early 1960s from Europe. This phenomenon is quite different from the “brain exchange” which occurs when a country’s talent inflow and outflow are relatively balanced, with roughly equal numbers of such individuals entering and exiting national boundaries. The “brain drain,” on the other hand, refers to a one-way outflow of highly skilled and educated people. It happens when “the outward migration of people with a higher education and in-demand skills exceeds a country’s ability to educate and train suitable replacements” (The Borderless Workforce, 2008: 6). The “brain drain” has long been seen as favoring developed countries, while damaging less developed ones. However, in recent years, observers have recognized benefits of “brain circulation” in the form of remittance, investment and knowledge from the skilled migrants (Gibson and McKenzie, 2011).

Since the onset of the 2008 Global Economic Crisis, developed countries have seen large numbers of the highly educated and skilled immigrants (and their families, including children) who had left emerging economies such as India, China, Russia and Brazil returning to their home countries. This phenomenon is referred to as the “reverse brain drain.” Returning migrants, who once went abroad in search of greater opportunities, are being lured back to their home countries by their high rates of economic growth. Some scholars argue that as the reverse migration trend intensifies, the “brain drain” is being transformed into a “talent flow” (Carr, Inkson and Thorn, 2005). Saxenian (2006) puts forward a theory of “brain circulation,” arguing that the “reverse brain drain” implies a one-way movement of global talent. “Brain circulation,” by contrast, reflects the circular aspects of this movement, which benefit the countries of both origin and destination of migrating talent. Drawing upon case studies of Israel, Taiwan, India and China, Saxenian (2002a, 2002b, 2006) argues that the circulation of entrepreneurial and technological returnees has provided benefits for the countries of origin of these immigrants. She shows that returnees who have developed their careers abroad play an important role in driving economic development in their home countries by bringing back human, financial and social capital.

To take full advantage of this new “circulation” phenomenon with respect to globally talented workers, many countries, including China, are developing innovative talent programs aimed at luring immigrants back home. These returnees constitute a cadre of highly trained and qualified people combining overseas education and valuable global experience with extensive local knowledge and social resources in their host countries (Tung and Lazarova, 2006). In 2006, China issued its Medium- and Long-Term Talent Development Plan (2010–2020), which seeks to expand the country’s team of innovators and cultural elites in order to transform it into an “innovation society.” In line with this overall plan, the Chinese government has successively launched a series of talent programs. These include the Thousand Talents Program and the Thousand Youth Talents Program, which were launched in 2008 and 2011, respectively, and sought to recruit “innovative” talent living abroad. This effort was especially targeted at overseas Chinese studying in foreign countries and was aimed at encouraging them to return to work for their homeland. The Thousand Talents Program aims to attract about 2,000 leading talented individuals under the age of 55, who have held professorships or equivalent positions in renowned foreign universities or research institutes over a period of 5–10 years. The Thousand Youth Talents Program plans to lure about 2,000 distinguished young overseas scholars under the age of 40 back to China by 2015.

Defining China’s returning talent pool

In the popular and highly influential book The War for Talent, Ed Michaels et al. (2001: xii) define talent as “the sum of a person’s abilities … his or her intrinsic gifts, skills, knowledge, experience, intelligence, judgment, attitude, character and drive. It also includes his or her ability to learn and grow.”

According to Solimano (2008), a talent pool consists of an elite group of persons “who apply their skills and ideas to the production, innovation, business, academia, research, and social and cultural activities” and “their rewards are mostly determined on the basis of people’s merit and contribution to widen the knowledge base and increase productivity and profitability of businesses.” He distinguishes four types of internationally mobile talent: (1) directly productive; (2) scientific; (3) health; and (4) cultural and social talent. In this book we adopt Solimano’s talent classification as an analytical framework to describe types of talented Chinese returning from overseas.

In our research, a returnee is defined as a migrant born in China who moved to advanced economies, especially the USA but also including other Western countries in Europe as well as Japan, or to other developing countries for higher education before returning to China to work on a permanent or long-term basis.

Realizing that overseas high-level talent is an important part of China’s human resource endowment, in March 2005 the Chinese Ministry of Personnel, the Chinese Ministry of Education and the Chinese Ministry of Finance jointly made a key announcement, which outlined the eight types of high-level overseas Chinese talent: (1) internationally known scientists, including pioneers in their respective fields or individuals who made remarkable contributions to their fields of study; (2) experts and scholars holding the position of associate professor, associate research fellow, or higher rank in a well-regarded overseas university or research institute; (3) senior managers in the world’s 500 largest companies, senior analysts in well-known multinational financial institutions or senior professionals working in law and accounting firms who are familiar with international rules and possess rich practical work experience; (4) experts or scholars holding down middle to top-management positions in foreign government bodies, international organizations and well-known non-governmental organizations; (5) accomplished scholars with great achievements in a certain field, with work published in top-flight peer-review academic journals, or having received academic prizes for doing globally influential cutting-edge research in a particular industry or field; (6) experts, scholars or technicians who have chaired large international scientific and research program or engineering projects, giving them rich scientific and engineering experience; (7) professionals with self-owned intellectual property, such as important technical inventions and patents; (8) talent that China urgently needs to attract.

Why Chinese returning talent?

China has made truly remarkable economic progress over the past few decades, becoming the world’s largest and most important emerging economy. It now holds the largest foreign exchange reserves in the world and its economy ranks second globally, surpassed only by that of the USA. However, despite its recent rise to global prominence, China’s economy must address a number of key issues in order to sustain this momentum. As the Chinese government recognizes, one such issue is upgrading the skills of Chinese workers. The cheap labor force has played a central role in the Chinese economic development model. However, as its population ages, China is losing its earlier “demographic dividend” of a bulge in the number of younger, working-age adults. This shift is already increasing unit labor costs in Chinese manufacturing, causing it to become less competitive against low-wage competitors such as Vietnam and Bangladesh.

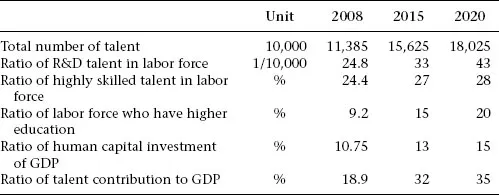

The Chinese government has set an ambitious target of transforming China into an innovative and creative economic powerhouse by 2020. The key to achieving this goal is developing and upgrading the country’s human capital. By all accounts, thanks to its still large population, China has substantial human resources in aggregate terms; lacking is a large pool of human capital. Attracting the innovative and creative talent needed to build a knowledge-based economy back to China is thus a critical and growing challenge faced by the Chinese government.

From demographic to talent dividend

For the past 30 years, China has thrived on its demographic dividend, which has provided the economy with a large and highly mobile pool of young working adults (the country currently still has more than 269 million1 migrant workers originally from the countryside) that kept its labor costs low. These low labor costs, in turn, played a key role in transforming the country into the “world’s factory,” with rising manufacturing exports fueling rapid economic growth. But this advantage is now being rapidly eroded by changing demographics, particularly an aging population and a declining number of workers, due to lower birth rates and the one-child policy, all of which will significantly diminish China’s position as an export platform for industrial goods relying on cheap labor.

One major challenge confronting the Chinese government is the increased demand for more social welfare public spending as the population ages. In July 2010, the Office of the China National Committee on Aging announced that the country experienced the largest annual increase in its senior population, with the number of people aged 60 and above growing by 7.25 million to 167.14 million in 2009, causing them to now account for 12.5 percent of the total population. The share of those 60 or older in the population is expected to explode from 16.7 percent in 2020 to 31.1 percent by 2050, which will put China far above the global average of about 20 percent. In the next 10–30 years, China will become an aging society and the demographic dividend that had fueled its earlier export-led growth will disappear. As China’s population ages, the burden on young people will increase.

In addition to its rapidly aging society, China faces up to another significant challenge in sticking with its current economic development model, namely the dependence on a cheap labor force. Worker compensation is now rising rapidly in the country, with the average annual growth rate of real wages amounting to 13.8 percent from 1998 to 2010, exceeding the Chinese real gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate of 12.7 percent over the same period. An urban household survey conducted in 2010 showed that wages grew for Chinese workers at all skill levels from 1998 to 2009 (Li et al., 2012). Growth rates of real wages for those with low levels of education (junior high school and below), medium levels of education (academic and technical high school) and high levels of education (college and above) are all increasing rapidly, growing at 6.5, 7.6 and 9.0 percent per year, respectively, clearly pointing to an overall rise in wages (Hongbin et al., 2012). As a result, China’s advantage of a cheap labor force in the global industrial chain is diminishing.

Moreover, China now faces a major employment crisis. The number of strikes by low-paid Chinese workers has risen dramatically. Much of this recent labor unrest, including work stoppages at Toyota and Honda plants in Southern China, strikes by Chongqing cab drivers and walkouts by employees at a major BMW distributor center, all serve as indicators that the cheap labor growth model cannot be sustained much longer. In August 2010 the cover story of The Economist highlighted Chinese labor unrest, noting that in the country’s factories, both pay and protest are on the rise.

Table 1.1 Main indicators of China’s national talent development plan

If real wages continue to grow at a 13.8 percent per annual, China will become a middle-wage country. When that happens, manufacturers will move from the country’s southeast coastal regions to the central and western regions, and then eventually to low-wage destinations such as Vietnam, India, Africa and South America, which will be better endowed with abundant low-cost labor and cheap land, while also possessing convenient transportation facilities. Thus China needs to shift away from an emphasis on low-wage, labor-intensive export sectors to higher-value-added manufacturing and innovation. In order to complete this transitional process, the country will have to create better-paid jobs in the service sector, which includes professionals, entrepreneurs, teachers, engineers, doctors, lawyers, accountants, consultants, artists, IT specialists, technicians and social workers, and also raise overall domestic consumption levels.

From manufacturing economy to knowledge-based economy

The key factor driving China’s past and current growth is not a high-tech industry, a knowledge-based economy, or innovation and creativity, but rather a cheap labor force, inexpensive land and low-end manufacturing. China had achieved some progress in the high-tech field, particularly in making computers and military technology, with the latter including nuclear weapons and satellites. However, these important achievements were oriented toward helping China catch up with Western countries, rather than establishing leadership in these fields. The source of the technological breakthroughs in these and other high-tech areas was none other than the USA.

The World Bank has identified four pillars of the knowledge-based economy: (1) education for a skilled workforce; (2) science and technology (S&T), and innovation; (3) information and communications technology infrastructure; and (4) an appropriate policy and regulatory environment (Asian Development Bank, 2007). Although China has a significant number of people who have benefited from higher education, the total size of the skilled workforce remains quite limited. Chi...