- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Beyond Diversity and Intercultural Management

About this book

Beyond Diversity and Intercultural Management develops a change model designed to challenge prevailing paradigms in the literature and conversations about equal employment opportunity, diversity, and intercultural management.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Beyond Diversity and Intercultural Management by C. Robinson-Easley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Human Resource Management. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

MY JOURNEY AND UNDERSTANDING OF DIVERSITY AND INTERCULTURAL MANAGEMENT FROM THE LENS OF TRADITIONAL PARADIGMS

CHAPTER ONE

UNDERSTANDING DIVERSITY FROM THE MINDSET OF A STRUCTURAL APPROACH TO CHANGE

Educated and trained in human resource management and organization development, I historically approached diversity from a pragmatic mind set. Yet, over the years I have learned that if individuals, organizations, countries, and global economies are to “make” diversity work in people’s daily lives, they have to embrace a mindset that transcends the traditional concepts of difference and resulting implementation strategies.

Throughout my travels, I have been exposed to a number of different cultures and contexts. As a result, my views on the concept of difference have been dramatically challenged. For example, I learned when working with international colleagues that the ordering of country culture, ethnicity, and ultimately race significantly varies and, as a result, impacts the individual’s perceived identity in ways you typically do not find expressed in the United States. Consequently, the concept of diversity is viewed from a very different context.

I embrace this change and continue to challenge my students to embrace different paradigmatic views on the concept of and constructs associated with difference especially when they examine the application of organizational change in concert with understanding how diversity can and does impact their self-efficacy, growth, and development.

The Mindset of Affirmative Action and Compliance with Equal Employment Opportunity Laws

I have also learned that the lowest level of work I had to do with regard to the concept of difference was dealing with affirmative action issues and their resulting legal ramifications. And, even in the twenty-first century, I still have to deal with issues of compliance and teach these constructs in the classroom.

While I am very well trained in the legal landscape of affirmative action and equal employment opportunity, each time I have had to “defend” a case for my organization in a regulatory hearing, or teach a class and hear students speak of their personal struggles with issues of inequality, I have struggled with understanding why organizations cannot evoke an egalitarian environment—despite their affirming to be an equal opportunity employer. What is it about difference that compels people to act in such a negative manner? Yet, over the years, I have also learned that the issues associated with equal employment opportunity are far more salient than just an organization’s inability to embrace difference.

In 2001, as I attempted to work through the cognitive dissonance I felt, I wrote:

To meet the demands of today’s technologically advanced society, organizations must rethink what diversity means and how the concepts of developing, valuing and managing a truly diverse organization must transcend traditional strategies. The traditional practices of engaging in programmatic initiatives to address diversity, such as diversity training, recruiting and hiring people from different backgrounds may not be appropriate for this millennium. New strategies, which incorporate successful, sustainable, and systemic organizational change processes are required to keep up with the systemic change that is impacting our world. These new strategies will need to incorporate organizational transformation, where in the deepest recesses of an organization, diversity becomes an internalized and realized part of the organization’s culture, norms and value systems and is displayed in every aspect of how an organization interacts and manages the workforce. (Easley, 2001, pp. 38–39)

Yet today, 12 years later, organizations still struggle with basic issues of compliance, which begs the question as to why, in this millennium, we still keep regulatory agencies in business. More succinctly said:

Twenty years later as we progress through a new millennium the reasons for addressing diversity are also changing. The advent of the twenty-first century, incorporated with technological advancements have broken many barriers which impact the way and frequency of how people in this world interact and communicate. The brick and mortar walls, which served as traditional barriers to working with people from different cultural backgrounds, are quickly being eliminated. As a result, in today’s technologically advanced environment, it is not unreasonable to think of an organization hiring a department from another country without those workers ever having to leave their location, or a college professor teaching students from all over the world in one internet classroom environment. Technology makes these types of human interactive arrangements possible. (Easley, 2001, p. 38)

If the walls and resulting barriers that separate people have been broken, why can’t we break down the mental walls that still invoke unwarranted issues with regard to our worldwide and very diverse workforces?

Diversity Management: Still a Valid Concept?

Despite this being a cliché, as we continue to move through the twenty-first century, the one constancy we continue to face is the rapidity of change. Traditional boundaries that were our previous comfort zones, separating people across many barriers such as country, region, or workforce, no longer exist. Our boundaries are global and our workforce is global, and as a result, there is a broader continuum regarding difference that organizations must navigate. While diversity management has traditionally been addressed from a localized context, intercultural management has traditionally assumed the international business focus. The literature continues to subtext these issues and their relative competencies and skills from different contexts.

The international business arena now forces intercultural competence at the individual level and is presumed to be associated with global career success. At the organizational level, intercultural competence is associated with business success (Morley and Cerdin, 2010). Yet, in the face of this change, we still approach understanding diversity and difference from traditional paradigms, which do not ready us for a rapidly changing landscape of difference.

Twelve years ago, I pondered if organizational leaders in the United States had actually learned how to build a true diverse culture that values difference, or if we, as a global society, are in a more sophisticated stage of compliance. Twelve years later, I am not comfortable with asserting that we have made the level of strides necessary to position us as global leaders in the landscape of understanding and navigating through difference.

In 1997, it was suggested that traditional barriers to diversity, which were easier to identify 20 years ago, had been replaced by more subtle forms that are embodied in traditional values, which provide us with comfort (Brief, Buttram, Reizensten, Pugh, Callahan, McCline, and Vaslow, 1997). In 2013, that is still a valid proposition. Yet, globalization and technology continues to connect people together in ways that were previously thought impossible; connections that result in new definitions and dimensions associated with the term “diversity” (Alvarez-Pompilius and Easley, 2003).

These connections have caused me to continue to ponder over whether egalitarianism, diversity, equity, justice, and intercultural competency are terms that represent varying dimensions of the same construct and are positioned along a singular continuum relative to requisite competencies. Can a true egalitarian context in which culturally competent people work exist when issues still emerge regarding basic respect for and management of difference, whether it is diversity of the people, diversity of organizational cultures, or a combination of both? (Easley and Alvarez-Pompilius, 2003).

In the earlier stages of my career, I felt comfortable separating the concepts of diversity, diversity management, affirmative action and intercultural competence. However, there are definite vantage points to age and experience; I no longer separate these concepts.

My experiences have taught me that the ability to effectively manage diversity on the home front requires the same skill set, heart, ethics, and respect as when managing in an intercultural environment.

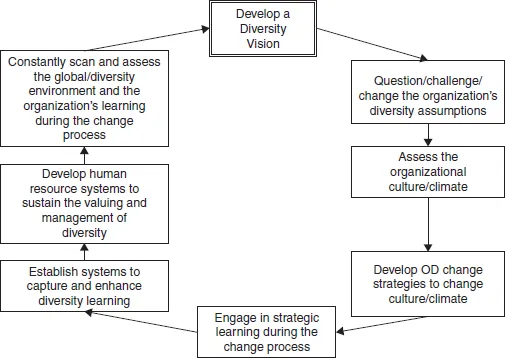

So, how did I come to this conclusion? My personal epiphany did not occur overnight. While I had authored and/or coauthored other works on diversity, I believed my first “serious” work on the topic was the article previously addressed, “Developing, Valuing and Managing Diversity in the New Millennium,” which appeared in 2001 in the Organization Development Journal (see figure 1.1). Having a combined practitioner and scholar focus, I began to research and challenge prevailing assumptions and dialogues with respect to what constituted the effective management of diversity. When I began working through the diversity questions that continued to plague me, I drew heavily upon my experiences in the corporate business sector. I have learned over the years that “he (and for sake of inclusion, I add)/ she who dares to teach must never cease to learn” (Richard Henry Dana Jr.).1

Figure 1.1 Model, Easley, 2001—Roadmap for Developing, Valuing, and Managing Diversity in the New Millennium.

Source: Easley, C.A., (2001). “Developing, Valuing and Managing Diversity in the New Millennium,” The Organization Development Journal 19( 4) (Winter 2001).

Over the years, I had witnessed organizations spending considerable sums of money on sensitivity training and diversity management programs. Yet, even when they were successful in recruiting a diverse population of individuals into the organizations, they struggled with retaining the people they recruited. Strategies such as diversity councils, focus groups, and similar types of endeavors to “hear” the voices of the underserved and underpopulated organizational members only served to anger people more. It was simply window dressing. Workers from diverse backgrounds would take considerable risk in joining these councils because they believed in the individuals who were championing their cause.

I soon began to understand that because many of the champions did not work in levels of the organizational structure that would allow them to be the drivers of real change, these initiatives had little impact upon the organization. The champions echoed in good consciousness and beliefs the concerns of their peers, but the real change would reside at the leadership levels of the organization—in the “C” suite and these were typically not the individuals attending these meetings with their workforce.

Even when I factored in that both sensitivity training and diversity management initiatives were fairly new strategies in organizations at that time, there still appeared to be something missing when these strategies were used. One of the more glaring questions those of us in human resources would ask was—how long would results be sustained?

When I wrote the Organization Development Journal article, I incorporated a model that was designed to move an organization toward effectively valuing and managing diversity. The conceptual framework of the model challenged traditional intervention strategies, such as training and suggested a multidimensional approach to changing an organization’s culture. The model also included assessment and intervention strategies aligned with processes designed to institutionalize the change; processes that were built upon organizational learning theory (Easley, 2001).

My criticism of training as a preferred diversity strategy was straightforward and was based upon my practical experience in the workplace and educational grounding in training and development. I also incorporated the perspectives of other researchers who also closely studied the effectiveness of diversity training. The critique of training as a preferred diversity strategy grew and, as a result, in the mid-1990s the literature that resulted from practitioners and scholars critiquing diversity training programs began to look robust.

During this time, the thinness of the empirical research was criticized by many researchers. Many questioned the real effectiveness of traditional interventions, the lack of clear objectives for the training initiatives, and the ongoing failures to give managers tangible standards for understanding how to interact with people from different cultural backgrounds. There were researchers who also suggested that the training programs yielded little change in day-to-day behaviors. Inclusively, many thought that the training strategies used resulted in increased hostile behaviors such as backlash, reinforcement of group stereotypes, post-training discomfort and group infighting (Golembiewski,1995; Grossman, 2000; Rynes, and Rosen, 1995; Paskoff, 1996).

I suggested in my 2001 journal article that change strategies as they related to diversity could not just be addressed in the context of training and recruitment initiatives. To properly understand the appropriateness of diversity interventions, one would need to delve deeper into the organizational issues. I also noted a need for organization leaders to discuss and come to grips with the organization’s commitments to the human element as part of their strategic decision making processes, inviting organizational members to the table when designing change processes.

During the same time frame, I worked on a consulting engagement where I was asked to provide diversity training to over 1,000 employees within a state organization. This organization had serious legal issues and was under a consent decree, which meant that their prior diversity initiatives had obvious flaws—points that will be further expanded in a later chapter.

Working with this organization brought to light other perspectives. As I suggested earlier, the subtle issues that drive people to suppress others will often emanate from spaces and perceptions of systems of domination—racism, class elitism, sexism, and imperialism—systems that should be acknowledged as behaviors capable of wounding the spirit (hooks, 1995).

Unfortunately, damaged spirits rarely choose liberation and/or change (hooks, 1995). We cannot ignore these realities because they drive the need for us to intentionally utilize our cultural points of reference for developing an attitude of liberation, whether it is from a personal and/or an organizational context (Hopkins, 2005). We should also factor in that when the organization wounds the spirit of the workforce, whether intentionally or not, they risk a psychological disconnect that will ultimately impact the organization’s effectiveness, which also impacts the organization’s ability to economically thrive. You see, organizational leaders should understand how their workers see themselves being oppressed.

Some say there is a duality in oppressed people. On one level they are themselves, and on another level they represent the image of the oppressor that they have internalized (Friere, 2006). I saw this duality in my working with this state agency and within other organizations I later worked with.

What has continued to intrigue me as I walked through seminary and examined various literatures, is that power and domination are common themes across far too many organizational and cultural contexts (Robinson-Easley, 2012). It is also quite interesting to examine how these varying cultures grapple with their status in life. For example, from my own lens, African Americans have been told that they are less than their white counterparts. Even in the midst of the abolishment of laws that eliminated the inability of African Americans to equally participate in the various institutions of life, we still get messages that we are not equals in this society (Robinson-Easley, 2012). Yet, it is not until those who see themselves being oppressed concretely discover their oppressor and in turn their own consciousness that they move past a fatalistic attitude toward their situation (Friere, 2006).

Therefore, when organizations are serious about evoking an environment that values difference, they have to be ready to move their membership to a space that allows them to be all that they are meant to be. This movement should be endorsed and led by the leadership of the organization. Yet, training initiatives rarely took organizations to this level, and they clearly were not designed to address the subtle and/or overt power dynamics that were c...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- Part I My Journey and Understanding of Diversity and Intercultural Management from the Lens of Traditional Paradigms

- Part II Nontraditional Venues for Evoking the Diversity Conversation

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index