- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

New Paths to Public Histories

About this book

New Paths to Public Histories challenges readers to consider historical research as a collaborative pursuit enacted across a range of individuals from different backgrounds and institutions. It argues that research communities can benefit from recognizing and strengthening the ways in which they work with others.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access New Paths to Public Histories by Margot Finn,Kate Smith in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Historiography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

From Competition to Collaboration: Local Record Office and University Archives, and the Country House

Helen Clifford and Keith Sweetmore

Abstract: Clifford and Sweetmore provide a historicised guide to the development of archives held in record offices, universities and country houses over the twentieth century. They demonstrate how long-established connections between the personnel, skills and documents embedded in these different sites have shaped the research practices undertaken by academic, local and family historians. By demonstrating how new research questions pertaining to the ‘global’ have led scholars to focus on different collections within national, county and local archives, Clifford and Sweetmore reveal that continuing collaborations between higher education institutions and repositories are important in maintaining the dynamism of archives and universities alike. They end their chapter with a consideration of the potential problems that might limit future connections.

Keywords: cataloguing; country archives; country house; local history; university archives

Finn, Margot and Kate Smith, eds. New Paths to Public Histories. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015. DOI: 10.1057/9781137480507.0007.

In this contribution we seek to map the developing relationship between county record offices and university archives, focusing on papers largely in country house collections from the North of England. Originating from our own collaboration as part of the East India Company at Home 1757–1857 project, this investigation is framed by a broader search for global connections within local archives. Our analysis, which begins just before the First World War, reveals the importance of individuals, in a narrative that is more usually viewed as corporate. The surprisingly maverick first county archivists, operating between the 1920s and 1940s, set patterns for collecting and cataloguing that have created the archival landscape in which local, family and academic historians still work. The model that was created was not at the time the only one envisioned. For example, the West Sussex County Archivist Dr Francis Steer (d. 1978) suggested that record office outstations might be created within the large country houses at Arundel and Petworth, as an alternative to the single-site model.1 This ‘prehistory’ of the country house archive is little understood. But it has had a crucial impact on how academic, family and local historians do business, and underpins the collaborative endeavours of both present and future historians.

In the first section, we present an overview of the evolution of both local record offices and higher education archives. In the second section, we discuss case studies that examine global connections embedded in North Yorkshire County Record Office (NYCRO), and their links to academic research via the East India Company at Home project. In the final section we consider the problems entailed in collaborative ventures between local record offices and Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) and how they can be addressed. In this section we particularly confront the problematic nature of current funding strategies and suggest the need for greater dialogue between funding bodies that work across university and local archive sectors. We also address the issue of access and how archives can seek to include and represent the diverse communities they serve in a digital age. This chapter tracks the legacy of the early archive movement and explores the shape of current and future collaborative working across the archive and university sectors.

Overview of the evolution of local record offices

The first English county archive service emerged in Bedfordshire in 1913 as a result of the exertions of George Herbert Fowler (1861–1940), remembered today as ‘the father of the English county record office system’. A successful marine zoologist, and lately assistant professor of zoology at University College London (UCL), Fowler brought groundbreaking methods and persistence to all aspects of local records work.2 His young protégés at England’s first county record office included such future elder statesmen of local archives as Frederick Emmison (1907–1995), founder of the Essex County Record Office in 1938, who retired in 1969 after a long and distinguished career.3 Eight or nine of Emmison’s staff became county archivists themselves: genealogies of training and influence can be traced from key figures such as Fowler and Emmison, and inherited traditions in systems for document referencing and office organisation can still be perceived in English record offices today. The story of the spread of county record offices is one of pioneering individuals – often young, always strong and practically minded and sometimes eccentric men and women with powerful vision and a missionary zeal.

During the 1920s and 1930s around a dozen southern English counties emulated the achievement of Bedfordshire, encouraged by highly vocal records preservationists, in a ‘movement’, which disseminated ‘propaganda’ to combat the loss and destruction of local records. With the outbreak of the Second World War, these efforts were redoubled in the face of national drives for paper salvage. The work of the British Records Association, established in 1932, and its Records Preservation Section (which originated under the auspices of the British Record Society in 1929) was ‘the most vigorous and effective mass action in the history of English archives’.4 Prime mover in this campaign was Ethel Stokes (d.1944), a record agent who established a strong voluntary tradition in records preservation, ‘and left the local records of England on an entirely different footing from the state of neglect in which she had found them’.5 Other supporters included Sir Charles Hilary Jenkinson (1882–1961) of the Public Record Office who went on to be deputy keeper there, and a powerful influence on English archival thinking and practice.6

A sudden flowering of English county record offices took place between 1945 and 1959. The growth of the English archive profession has attracted little formal study, with the notable exception of the work of Elizabeth Shepherd, Professor of Archives and Records Management at UCL. Shepherd identifies five early ‘models’ for the development of local archive provision, and analyses the drivers for the development of local offices in detail.7 Early provision for local archives was piecemeal, pragmatic, uneven and largely unsupported by clear central direction, much less any legislative or central financial support. County record offices evolved within a wider informal network of activity: some borough libraries had a long tradition of holding manuscripts, several county archaeological societies acquired records, older-established universities had their special collections and specialist and voluntary libraries and museums held archives too.

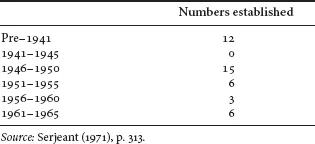

In Yorkshire, for example, the Archaeological Society began collecting archives in the later nineteenth century. The West Riding never established a county record office; from the 1930s until 1974 archives were collected primarily by the city libraries of Leeds for the northern part of the Riding, and Sheffield for the south. York and Hull appointed city archivists in 1957 and 1968 respectively. The North Riding established a county record office in 1949, and the East Riding in 1953.8 York University’s Borthwick Institute of Historical Research was established to house the archives of the Diocese of York in 1953. From 1974 new joint arrangements for the metropolitan county of West Yorkshire attempted to create ‘a better and more equal level of service’ bringing archive holdings in Bradford, Calderdale (Halifax), Kirklees (Huddersfield) and Leeds and Wakefield under single management, and this joint service survived the abolition of the Metropolitan County Council in 1986.9 In South Yorkshire less integration was achieved, and the archives of Sheffield, Barnsley, Rotherham and Doncaster continue to operate under separate authorities. It is perhaps surprising that the existence of a county record office became the norm. A survey for England and Wales carried out in 1985 provides the following data on establishment dates (see Table 1.1).10

By 1992 all but one of the shire counties in England and Wales (Avon) had a record office.11 Local archivists, operating in a variety of settings, displayed the independent action and self-sufficiency of true pioneers. Ultimately county record offices prevailed as the basis for the informal national network of archival provision.

TABLE 1.1 Survey of establishment dates for county record offices in England and Wales, c.1941-1965

County archives and the great houses

The overt objective of the new county record offices was to identify, preserve and make available official county records. Typically these would include the archives of the County Council from 1889 onwards, and its predecessor the Quarter Sessions, including judicial and administrative records dating back to at least the seventeenth century. But from the outset, ambitions were wider, and there were clarion calls to ‘get the documents in’. ‘Non-official’ records came from a wide variety of sources, including diocesan registries, parish chests, muniment rooms of great houses and the basements and attics of solicitors, schools, charities and businesses. They were collected in ever-growing quantities, despite the lack of any statutory authority to do so. Moreover, most estate archives would contain a significant volume of ‘out-county’ material, another feature that a county archivist might prefer to keep quiet. As one prominent county archivist put it, ‘a whole swathe of our duties were ... “a-legal” if not illegal’.12 Another veteran of the post-war years recalls ‘an unspoken understanding that archivists had an agenda that need not necessarily be revealed to the funding authorities’.13 While a county could spend money on its own records, spending on non-official documents could in theory be challenged, declared ultra vires and councillors surcharged with it. While this remained a perceived threat until the Local Government (Records) Act of 1962 regularised the position, it plainly did little to deter the intake of estate and family archives. On the contrary, the acquisition of some large private collections acted as a spur to provision by the local authority. The archives of the Marquesses of Aylesbury of Tottenham House, Wiltshire were received by Wiltshire in 1947 on condition that ‘the County Council should appoint a properly trained archivist ... to classify and calendar them and to superintend their repair’.14 Many such deals were arranged by the National Register of Archives, established in 1945, and its first Registrar, Colonel George E.G. Malet (1898–1952) – scion of a family whose links to the East India Company and the Indian empire date from the eighteenth century. The Wiltshire appointment ‘was by no means the only case where Colonel Malet’s persuasiveness with owner and authority alike speeded up development’.15

As county record offices flowered in the post-war years, the ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- 1 From Competition to Collaboration: Local Record Office and University Archives, and the Country House

- 2 Collaborating across Heritage and Higher Education to Reveal the Global History of Osterley Park House

- 3 Creating Collaboration: Accessing the Archive

- 4 Outside the Public: The Histories of Sezincote and Prestonfield in Private Hands

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index