![]()

1

Introduction

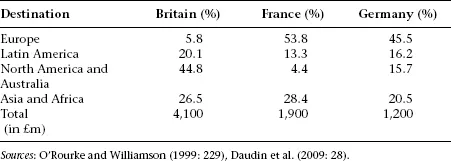

The period from the 1870s to 1914 was the peak of the nineteenth-century globalisation characterised by increased movement of capital across the world.1 Britain – specifically, the London market – was the major source of foreign capital flows, accounting for 62 per cent of foreign investment in 1870. In 1914, Britain (at 43 per cent), France (20 per cent) and Germany (13 per cent) together accounted for 76 per cent of total foreign investment (see Table 1.1). The major part of the remaining investment was held by Belgium, the Netherlands and Switzerland.2

As regards the form of the foreign investment, roughly three quarters of European capital flows before 1914 was on portfolio investment and mainly sovereign lending rather than direct investments. Regarding the destination of capital flows, at the turn of the century, London, Paris and Berlin had become the borrowing centres for the governments of the peripheral countries of Latin America and Eastern and Southeastern Europe. On the eve of the First World War, the peripheries of the British Empire, including Canada, Australia and India, absorbed nearly one-half of British investment. Latin America and the United States attracted over 20 per cent of British investment. At the same time, more than half of French and German capital was financing Europe, including Russia and the Ottoman Empire.

Table 1.1 Distribution of European foreign investment, 1913–1914

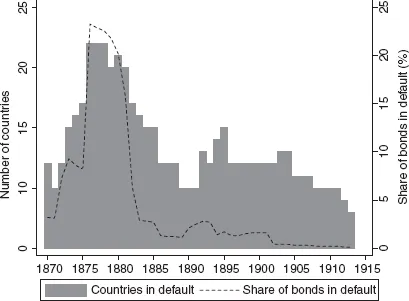

Throughout the period, the rapid increase in capital flows in the form of sovereign debt was punctuated by defaults on foreign obligations in many debtor countries, including Tunisia (1868), the Ottoman Empire (1875), Egypt (1876), Spain (1877), Argentina (1890), Portugal (1892), Greece (1893), Serbia (1895) and Brazil (1898).3 For the period 1870–1913, it is possible to identify two distinct waves of sovereign defaults taking place in 1875–1882 and 1890–1900 (see Figure 1.1).4 In the first wave, the total number of countries on default on their foreign obligations reached a peak in 1876 with 14 countries. Moreover, the share of foreign bonds in default relative to total foreign investment of core countries amounted to almost 25 per cent. In the less severe second wave only eight countries were not able to comply with their terms of the debt contracts, and in a parallel way the increase in the volume of bonds in default was relatively small. Response to these defaults varied from case to case and evolved as the century progressed. Sanctions included seizing the assets of a debtor country through military intervention, trade restrictions, preventing access to future credit and finally putting debtor nations under “international financial control” or “fiscal house arrest” by introducing foreign administrators, who were authorised to collect specific tax revenues of debtor states.5

As for the economies of the Middle East and the Balkans, the first era of financial globalisation was a period of integration with the world economy through flows of commodities and capital. During this period the agricultural sector in the region considerably commercialised and the export-oriented agriculture became norm. The major regional power, the Ottoman Empire, gradually lost its influence due to territorial decline and imperialist rivalry in the region. Both the succeeding newly independent states and the Ottoman Empire had to face with new military, political and economic challenges under these circumstances. Therefore, the region as a whole was characterised by costly and frequent wars, ambitious reforms to modernise the state apparatus and armies, and expensive infrastructure projects such as building railways for mobilisation of troops and commodities. However, the ability of the states to meet these big expenses via taxation was not always possible. Given the limited size of domestic financial markets, the shortcut solution to the problem was found in foreign borrowing. As a result, the countries of the Middle East and the Balkans joined international financial markets in the second half of the nineteenth century, followed by a rapid expansion in outstanding debt levels. In terms of volume of debt, the leading borrowers of the region were the Ottoman Empire, Egypt and Tunisia. In the Balkans, Romania, Greece, Serbia and Bulgaria contracted a significant number of foreign loans. In the Ottoman Empire, Egypt, Greece and Serbia, the accumulation of debts led to insolvency in 1875, 1876, 1893 and 1895, respectively. In these four cases, following defaults, the solution of financial markets was to introduce international financial control (IFC) over the finances of debtor states to compensate the loss of foreign creditors through regular transfer of revenues. Although a large body of legal, economic and historical literature has explored the historical dimension of the debt crises, their solution and the negotiation of resettlement agreements between debtor countries and their creditors before 1914, there have been very few attempts to study the history of sovereign debt and the IFC experience of the Middle East and the Balkans from an analytical and comparative perspective.

Figure 1.1 Number of countries and volume of bonds in default, 1870–1913

This book aims to fill this gap by comparing the history of sovereign debt, moratoria and creditor enforcement in the Ottoman Empire, Egypt, Serbia and Greece from 1870 to 1914, when international capital flows were at their peak.6 The selected case studies, among other things, share a common history in the enforcement mechanism adopted by the creditors to deal with the moratoria. All countries experienced the establishment of IFC by the representatives of foreign creditors, which were assigned the task of administering and collecting certain tax revenues of debtor states in order to compensate for the unpaid interest and capital of foreign debts. This resulted in a partial loss of fiscal sovereignty in each debtor country with different degrees. Foreign supervision also implied changes in the institutions, because IFC actively interacted with ruling elites and actors, and transformed economic, fiscal and political structures. In Egypt, the establishment of the Caisse in 1876 became a prelude to a direct takeover of the state finances in 1882; in the Ottoman Empire, the Council, founded in 1881, dealt with direct collection of taxes and was involved in administrative and tax reforms; in Serbia, the Administration was founded in 1895, and its activities concentrated on running major state monopolies; and in Greece, the Commission, founded in 1898, consisted of diplomatic representatives of lender countries, and it mainly focused on putting forward particular measures concerning monetary discipline.7

Traditional national historiographies usually approach IFC in the context of imperialism debate, since one of its consequences was the partial loss of fiscal and/or political sovereignty of the debtor states. This book revisits the conventional view by focusing on the costs and benefits of IFC from a comparative perspective, and analyses the interplay between IFC, creditors and fiscal regimes of each country. History of sovereign debt, default and IFC are discussed on a case-by-case basis in detail to contribute to the national historiographies on the subject. Moreover, the book draws comparisons between cases along the themes of creditworthiness and fiscal capacity. In order to identify and explain the impact of different practices and policies implemented by each IFC, I first estimate and analyse the sovereign risk of each country. I then propose a framework to interpret the success of foreign control in restoring credibility and in collecting revenues.

The key argument of the book is that the performance of IFC was not uniform in the region; there were substantial differences in reinforcing credibility and administrative structure. Moreover, the extent of control exercised varied in each case. In explaining these variations, I propose that the IFC reinstated credibility more effectively, if the defaulting governments of the region were more willing to cooperate with or were not able to pose a political challenge to the control. In the second stage of the analysis, I suggest that the lack of resistance to IFC was a function of the absence of representative political institutions, which enabled the defaulting governments to keep relying on the heavy taxation of the rural sector via direct taxes but at the same time led to high tax collection costs. As a result, the debtor governments without representative political institutions were more willing to transfer economically and politically costly tax collection business to the hands of IFC in exchange for future credibility. On the other hand, if the defaulting countries had functioning representative political institutions, they were forced to take into consideration the demands of the sizeable agricultural sector. Reducing the tax burden of the countryside meant a shift towards indirect taxation well before IFC was established; therefore, the political elite was not as keen to share the revenues with foreign creditors.

The importance of IFC experiences of four countries goes beyond contributing to the economic and financial history of the region and to our understanding of the governance of sovereign debt before 1914. One of the implications for the broader economic history literature is the role of IFC in determining fiscal capacity. As briefly outlined above, the key argument of this book implies that as oppose to the standard narrative8 having representative institutions did not necessarily mean an automatic improvement in the cost of borrowing. Similarly, lack of limited governments and representative institutions did not inevitably translate into inability to borrow in international markets. In other words, for the relatively poor, agricultural and open economies of the region, ability to borrow with low interest rates and on a long-term basis did not reflect a strong state capacity since IFC served to reinstate the credibility of the weak states of the region. In fact, the more successful was IFC in their task of reinforcing creditworthiness, the more it slowed down the march towards fiscal centralisation and transition to fiscal states in the Middle East and the Balkans.

The book is structured very broadly in two parts. The first part (Chapters 3–6) documents the history of sovereign debt and IFC in Egypt, the Ottoman Empire, Serbia and Greece individually from the start of external borrowing to the moratoria and the foundation of IFC. The presentation follows the chronology of emergence of IFC in the region. Here the aim is to provide a picture on the extent of integration via international capital inflows, relationships with the creditor states, events leading to defaults and finally foundation and implementation of IFC. Most of the historical narrative relies on primary sources in particular the records of the Corporation of Foreign reports of each IFC, British parliamentary papers and consular reports and other contemporary sources. In the second part (Chapters 7–8) the differences in microstructure of each IFC, the legal administrative framework in which they implement their activities, and finally the impact of these elements on the performance of foreign control are discussed in a comparative way. The first part of this comparison focuses on the impact of IFC on sovereign risk of each country. Another comparative chapter highlights and develops a framework to interpret different degrees of cooperation with the foreign creditors and success record of IFC. The chapters can also be read as independent pieces on each case and theme. Moreover, a comprehensive data appendix is provided to enable the interested reader to reproduce the figures and the analysis.

The remainder of the book is organised as follows. In Chapter 2, I review the literature on the governance of the sovereign debt market before 1914 with particular reference to the causes of sovereign debt crises and the response of creditors to defaults. I provide an overview of international institutional context within which the borrower countries of the Middle East and the Balkans contracted loans, defaulted on their obligations and finally were faced with financial control. I revisit the topical questions of why countries default and what determine the ability of countries to repay their debts to highlight the mechanism of sovereign debt. Moreover, the chapter focuses on a unique characteristic of sovereign debt contracts: different degrees of immunity between the contracting parties. In reviewing the answers, it predominantly focuses on the conditions of the sovereign debt market before 1914 and provides an outline of different types of enforcement mechanisms, which emerged and remained in operation during the first era of financial globalisation. A significant part of the discussion is dedicated to the mechanism of assignment of future revenues to secure sovereign debt contracts and the subsequent control of these revenues by foreign creditors in the case of a default.

Chapter 3 documents the functioning of IFC in Egypt from its early years until 1914. Egypt can be considered as an exception among the cases of this book, because IFC eventually served as a prelude to de facto colonisation of the country after the British military intervention in 1882. Therefore, unlike other cases, Egypt lost its political sovereignty and Egyptian government had no choice but to comply with the foreign creditors. Consequently IFC functioned in a more complex political and institutional environment, where imperialist rivalry over controlling Egypt gave direction to the formation of different instruments of political, fiscal and financial control. The discussion draws heavily on these historical characteristics to untangle the impact of the IFC from the broader colonial history of Egypt. Chapter 4 provides a brief history of international financial control as experienced in the Ottoman Empire from 1881 to 1914. In the first section, I provide the longer-term context and give a historical outline of the accumulation of sovereign debt, which started in 1854 and ended with a catastrophic default in 1876 stirring international financial markets. The second part of the chapter deals with the activities of the IFC by mostly relying on the reports of the Council of the Ottoman Public Debt Administration. These two cases, despite significant differences, can be considered as the early history of IFC in the region, characterised by the implementation of more direct methods of interference to the finances of defaulting countries.

In Chapter 5 and 6, I explore the IFC experiences of Serbia and Greece, both defaulted during the 1890s. Following the chronological order of appearances of IFC in the region, in Chapter 5, I look into Serbia’s experience of foreign control, which was established in 1895 – just three years earlier than the Greek case. I discuss the functioning of the Autonomous Monopoly Administration of Serbia, which represented a transition from direct fiscal control of creditors to a less intrusive method of financial supervision. Chapter 6 elaborates the final case of IFC, which was established in Greece in 1898 following the default of 1893. The Greek case pictures a different form of control where the IFC operated through an independent company, its role was reduced to a supervisory one, and as a result its impact on overall creditworthiness of the country remained relatively minor. In line with this argument, I outline the history of sovereign borrowing from the Greek independence loans in 1820s to the establishment of the IFC in 1898, and then discuss the activities and organisation of the IFC from 1898 until 1914.

Chapter 7 brings together some of the evidence presented in the previous chapters around the question of the impact of IFC over sovereign risk. It provides a comparative and analytical framework and pictures the long-term evolution of sovereign risk in the Middle East and the Balkans. By relying on an original monthly dataset of government bond prices, I implement the econometric technique based on the Bai-Perron structural break test in order to identify the structural breaks in bond spreads. I combine this statistical analysis with historical interpretation of break points based on the contemporary press to shed light on investor behaviour towards the Ottoman, Greek, Serbian and Egyptian gover...