- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Performance and Temporalisation features a collection of scholars and artists writing about the coming forth of time as human experience. Whether drawing, designing, watching performance, being baptised, playing cricket, dancing, eating, walking or looking at caves, each explores the making of time through their art, scholarship and everyday lives.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

World • Space • Place

1

Timing Space–Spacing Time On transcendence, performance, and place

Jeff Malpas

All the vital problems of philosophy depend for their solution on the problem what Time and Space are and more particularly how they are related to one another.

Samuel Alexander

1. Can we think temporality without also thinking the spatial? Might not the thinking of temporality always implicate the thinking of the spatial along with it? It might be thought that this question is already answered in modern physics by the notion, appearing in Minkowski et al (1923), but also present, for instance, in Samuel Alexander (1920), of space and time as a continuum, as space-time. My interest here is not merely with the thinking of space and time as they occur as formal elements within physical theory, however, but rather with a more fundamental understanding of these concepts as they belong to the very framework of experience. What is at issue is not merely a question concerning the nature of the temporal alone, but of the unity of time with space, and so also of the character of event, action, and performance, and of these as spacings no less than timings. The idea of the unity of time with space, expressed in the notion of ‘timespace’ (Zeitraum), is a central idea in the development of Martin Heidegger’s thinking as it moves away from the problematic treatment of time and space that is evident in Being and Time.1 On this account, there is no temporality that does not bring spatiality along with it, and no spatiality that does not bring temporality also. Understanding the unity of timespace is to understand the unity of place. Indeed, it is only in and through that unity, which is also always a working out of plurality, that there is any possibility of the transcendence that is so often associated with art and performance, as well as with philosophy.

2. There is a longstanding history that gives priority to time over space, and that remains within contemporary thinking in spite of the apparent reduction of time to a single mode of dimensionality within contemporary physics (a reduction that is itself in keeping with that spatialised conception of the world that is in turn dependent on a highly specific understanding of the spatial that is tied to the measurable and the calculable that dominates within modernity; understood as measurable, time can only be assimilated to the spatial, since time carries within it no mode of determination that would allow for such calculation or measure). Indeed, as spatiality increasingly came to dominate within the philosophy of the natural world (a dominance clearly established in the work of Descartes), so time came to dominate within the thinking of the human and the experiential. Within the Western philosophical tradition, the prioritisation of the temporal is already evident in the work of Christian thinkers such as Plotinus and Augustine. The idea is also a clear element in the German Idealist tradition, perhaps most notably in the work of Friedrich Schelling. In his System of Transcendental Idealism, Schelling is quite explicit in giving priority to time over space, treating time as itself tied to the activity of the self. The argument that appears in Schelling can perhaps be seen as adumbrating the claims for the priority of time that are such an important element in Heidegger’s Being and Time.

The rise of temporality as a concept distinct from the spatial (a distinction itself driven by the parallel rise of spatiality within physical theory) is evident, not only in the rise of historical modes of thinking that characterise especially the nineteenth century, but in a view of the historical and the temporal as almost one and the same. Indeed, so unthinking has this identification become that it may seem strange to suggest that such an identification is even questionable – yet, as has been recognised by twentieth-century historians, especially those influenced by the work of such as Lucien Febvre and Marc Bloch, history encompasses the spatial no less than the temporal, referring us to a way of understanding the past and the present, and so the concrete actuality of our existing spatialised world, no less than it also directs us towards the future (Malpas, 2008).

The treatment of the temporal and the historical as belonging essentially together is itself something evident in Heidegger. Indeed, Heidegger’s own prioritisation of the future can be seen as itself an expression of the prioritisation of the temporal. It is futurity that is taken by Heidegger to lie at the heart of temporality (that on which the unity of temporality properly depends), while the mode of temporality associated with the present, and which is also that which tends towards the spatial, is specifically designated in terms of ‘Fallenness’ – Verfallen (similarly that which has been, the past as given in facticity, or thrownness, is also secondary to futurity). The priority of temporality in Being and Time is made clear by Heidegger’s declaration near the very beginning of the work that its aim ‘is the Interpretation of time as the possible horizon for any understanding whatsoever of being’ (1962, p. xix). Indeed, the first two divisions of the work are partly distinguished by the way they focus, in the case of the first, on space and, in the case of the second, on time.

In Part One, Division One, of Being and Time, Heidegger sets out an account of the existential spatiality of Dasein that treats it as lacking any proper unity within itself. Heidegger argues that in space understood in a purely Cartesian sense, there cannot even be any relatedness, while he takes the structure of existential space, although teleologically structured, to result in a dispersal of Dasein into its externalised projects (the very extendedness of space means that Dasein is spread out into the world through its projective spatialised involvement so that it easily loses itself in that spread-out worldly spatiality). The argumentative and analytical movement of Being and Time is towards a demonstration of the way in which the unity of Dasein, including any unity in Dasein’s own spatiality, is given in the unity of originary temporality – it is this that is indicated by the characterisation of time as the horizon of being. It is for this reason that futurity, and being-towards-death, loom so large in Heidegger’s magnum opus. Heidegger is not, of course, the only late-nineteenth or twentieth-century thinker to move in this direction. Bergson also argues for a prioritisation of time over space, in his case in regard to self and mind. Moreover, he specifically sets one form of the temporal, as duration, over and against a spatialised mode of temporality that is viewed as secondary to it.2

The underlying reason for the prioritisation of time in Heidegger’s thinking is undoubtedly that time is often seen as associated with the ordering, often understood teleologically, that gives determination to things. In Heidegger and Schelling, time is thus understood in relation to activity, and it is activity, we might even say performance, that marks out the otherwise static and lifeless field of spatiality. Given that the spatial is frequently taken to be co-extensive with the material (something all too evident in the Heideggerian account of Being and Time in which Cartesianism is taken to exemplify an ontology inseparable from spatiality as such), one can see even more clearly how time may indeed be viewed as dynamic and determinative, in contrast to the static and undifferentiated character of space. This way of thinking is exemplified, not only in Heidegger and Schelling, but also, one might argue, in Bergson as well as in those many philosophers, including, for instance, Whitehead, who give priority to process or becoming, and who understand this priority as itself a prioritisation of the temporal and the durational. This tendency extends into contemporary discussions, particularly those that are concerned with understanding mental life or the nature of the self, since the psychological is typically understood (even when it is seen to stand in an essential relation to the body) precisely in its character as temporal (the body is often taken up into this frame in terms of its character as active – see, for example, Zahavi, 2002).

The dominance of temporality and temporal modes of analysis is evident not only in recent and contemporary philosophical treatments of space and time, but also in the way in which we use spatial and temporal language. We often use forms of speech that contrast temporal and spatial terms in ways that appear to accord a more positive evaluation to the temporal, or to that which is itself understood as aligned with the temporal, over the spatial. Thus we favour the dynamic over the static; movement over structure; the historical over the geographic; the futural over the past and the present (the spatial itself being identified with that which already is or has been).

Certainly there are significant counter-tendencies here, especially in regard, for instance, to the last of these, but those counter-tendencies typically remain counter-tendencies that operate against a more deep-seated disposition. Indeed, it is intriguing to see how, in many cases, the focus on the temporal is even taken to carry a more positive political and ethical import. Thus one frequently repeated criticism of German thought and culture (perhaps surprising given what I have said about Heidegger and German Idealism) is its preoccupation with what are taken to be essentially spatialised ideas and images (see, for example, Blickle, 2004). The spatial is thus associated with the conservative and the backward-looking: it is thus that the spatial also comes to be associated, once again, with the past. On the other hand, the concern with temporality, understood in terms of a focus on futurity (a connection evident in Heidegger), is seen to be politically and ethically progressive.

3. I want to return to the consideration of some of the philosophical history of the relation between time and space, and Heidegger’s own thinking, in a moment, but first I want to make what may appear to be something of a digression. Much of my own work occurs in a space between Heidegger and the American philosopher Donald Davidson. Although not something that Davidson has himself thematised, the issue of the relation between time and space appears in an intriguing way in Davidson’s work, and especially in the engagement between Davidson and the artist Robert Morris.

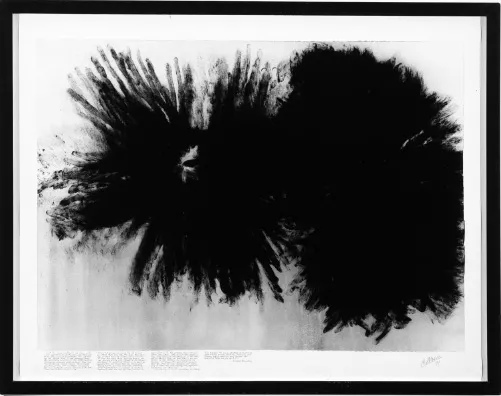

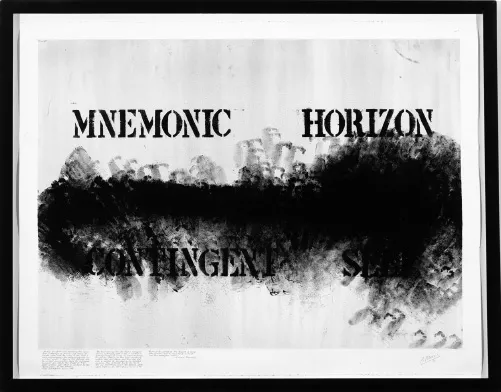

In the early 1990s Morris completed a series of works titled Blind Time Drawings. The works led to an exchange of comments between Davidson and Morris (Davidson wrote an essay for the exhibition catalogue, while Morris contributed an essay for Davidson’s Library of Living Philosophers volume). The works consisted of graphite, or sometimes graphite mixed with oil, applied to large canvases which already had certain symbols or marks imprinted on them, as well as passages of text, one section of text describing Morris’s aim in the work, along with some background, and one section being a quotation from Davidson’s writing on action. Davidson treats these works as showing the potential gap between action and intention; Morris emphasises the character of body and vision, discussing the way in which the works aim, through their imposed constraints, to explore the conditions under which artistic creation is possible, and particularly the role of the body and action in such creation.

Figure 1.1 Blind Time Drawings IV (Drawing with Davidson), Artist: Robert Morris

Figure 1.2 Blind Time Drawings IV (Drawing with Davidson), Artist: Robert Morris

It is significant that Morris names these works Blind Time Drawings IV (Drawing with Davidson). They are drawings inasmuch as they are produced using one of the traditional materials of drawing, namely graphite, though unusually applied (in one case Morris uses a towel to make the marks). But they also involve, quite explicitly, time, and also, through the constraint they impose on perception, space. Temporality appears in the works through Morris’s imposition of a time limit on the actions he performs, a time limit that he has somehow to meet without being able to check on that time as measured by clock or watch, and his own estimation of the timing of his actions. Spatiality appears through the way in which, by blindfolding himself, Morris changes the character of his experience of space and his engagement with the action and his materials.

Morris’s performances are described by Kenneth Surin as follows:

The materials used in the Blind Time Drawings IV are graphite or graphite mixed with oil. Morris typically gives himself a preset task to be accomplished within a time established in advance. The tasks vary: negotiating quadrants on the page, making regular movements of the mixture-smeared hand toward the (sensed) edge of the page, joining angles at the center of the page, enlarging a cross already placed on the page, moving rotating hands along a guessed diagonal, and so forth. Each drawing contains two texts: an excerpt from Davidson’s writings and, adjacent to this, an inscription by Morris outlining both the physical movements he sets out to make and the intention that underlies the task. (2002, p. 167, n. 12)

It is thus that these are indeed ‘blind time drawings’. They are executed within a time frame, though through a timing made by the artist. They are executed in a set spatial frame, but one that the artist has deliberately disabled himself from engaging with in the usual way. Both time and space are available to the artist only through the artist’s immediate experience of his located, embodied engagement in the performance, in the action. If one examines the deviation in the times attached to these works, those deviations vary considerably: +1.43, +.20, −.23, +1.16, −.48, −2.08, +.15, −1.36, −.44, −.52. There is no obvious correlation between the deviations in time and features of the completed works. Undoubtedly those deviations relate to some aspect of Morris’s own engagement in the performance, although one cannot say whether he was more or less accurate according to his immersion in the act, his feeling of satisfaction or dissatisfaction – we are not told. We are also not told how long Morris dedicated to each performance, and so cannot judge whether these were small errors relative to the elapsed time, or large ones. What does seem clear, however, is that the sense of time is itself variable in a way that can presumably only re...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Series Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on Contributors

- Introduction

- Part I World • Space • Place

- Part II Self • Movement • Body

- Part III Image • Performance • Technology

- Part IV Apotheosis

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Performance and Temporalisation by Jodie McNeilly,Maeva Veerapen, S. Grant in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.