- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Animals and African Ethics

About this book

The claim is frequently made on behalf of African moral beliefs and practices that they do not objectify and exploit nature and natural existents like Western ethics does. This book investigates whether this is correct and what kind of status is reserved for other-than-human animals in African ethics.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

African Philosophy

When we pose questions about the origin, the purpose or the central concerns of ethics and morality, we imply that there may be a difference between ethics and morality. A distinction is, indeed, commonly made between ethics and morality. Morality is the idea that some behaviour is good or right and that other behaviour is bad or wrong. Ethics is generally taken to mean moral philosophy – that is, philosophical reflection and enquiry concerned with morality and its principles and values, as well as with its judgements and problems.

An important way to get a handle on African ethics, therefore, is to examine its natural ‘home’, namely African philosophy.1 But what is African philosophy? Is there a body of thought, a way (or ways) of thinking, that can be described as distinctly ‘African’? The problem is articulated succinctly by Kenyan philosopher Henry Odera Oruka:

My inspiration in delving into sage philosophy [African moral principles extracted from the orations of village elders] was an attempt to try to establish whether or not Africans were capable of philosophy. ‘Am I, Odera Oruka, capable of philosophy?’ They say, ‘Yes, but it is because you have been to European universities.’ So, however great a contribution I could have made in, say, logic, metaphysics, or ethics, they would say, ‘Yes, fine, but this is European philosophy.’ And they would still wonder whether there was anything that Africans could contribute to philosophy that is authentically African. (Oruka 1997: 182, quoted in Peterson 2013: 86)

African philosophy might be understood essentially as a social practice. I will argue, towards the end of this chapter, that the value and distinctness of African philosophy emanates from its responses to the continent’s ‘unique and endemic’ problems, environmental (such as deforestation and desertification; see Peterson 2013: 862 and Horsthemke 2009b) and other, and is arguably constituted by its (characteristically) practical philosophical priorities – priorities that exist, at best, to a lesser extent (if at all) elsewhere.

Modes of African philosophy

Perhaps significantly more than philosophy elsewhere, African philosophy has been marked indelibly by the colonial experience. Historically, and for reasons of graphic illustration, it might be divided into its precolonial and postcolonial manifestations. Precolonial African philosophy had, with very few exceptions (Egypt comes to mind here), an essentially oral tradition. The written tradition came with and succeeded colonialism, exemplified inter alia by missionary education. Ethnic philosophy and sage philosophy characterise the former, while political philosophy and critical (academic or ‘professional’) philosophy exemplify the latter.

Ethnic philosophy consists of folkloric traditions, legends, stories and myths, and it survives in the postcolonial period in both oral and, importantly, written forms. So does sage philosophy, initially the spoken words and teachings of a few ‘wise men’ or ‘sages’, now also documented in writing. Nationalist-ideological philosophy and academic philosophy, on the other hand, are marked – if not determined – by the colonial experience. The writings and documented speeches of politicians, statesmen and prominent liberation movement personalities such as Kwame Nkrumah, Julius Nyerere, Léopold Senghor, Kenneth Kaunda and Steve Biko, to name only a few, constitute political philosophy that often also has a nationalist-ideological character. A fourth trend in African philosophising is the direction pursued by ‘critical’, ‘professional’ or ‘academic’ philosophy (see Oruka 1998, 2002). This is a direction associated with, for example, the writings and other contributions of professional philosophers and academics such as Kwame Anthony Appiah, Paulin J. Hountondji, Peter Bodunrin and Kwasi Wiredu.

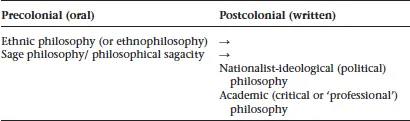

Although both Oruka and Ghanaian philosopher Kwame Gyekye can be credited with recording, concurrently and independently from one another, contemporary non-academic intellectual traditions (Lölke 2001: 140), Oruka was the first – that is, in 1978 (Oruka 2002) – to undertake this classification. He later (Oruka 1998: 101, 102) described two additional types of philosophy – the hermeneutic trend and the artistic or literary trend – somewhat unhelpfully, because the former appears to be subsumed by critical or ‘professional’ philosophy, whereas the latter contains elements of the other trends identified previously, namely ethnic philosophy, sage philosophy and political philosophy. These different kinds of philosophy and philosophising can be illustrated in the following manner:

It is important to note that ethnic philosophy and sage philosophy have survived colonialism and that they continue to thrive in postcolonial Africa. Both political and critical philosophy frequently exhibit or seek to validate elements of the former kinds of philosophy. Indeed, the number of academic or professional philosophers repudiating substantial elements of their African doxastic and conceptual heritage remains fairly small.

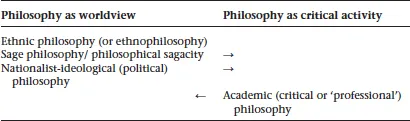

A further distinction might be made at this juncture between philosophy as ‘worldview’ and philosophy as ‘critical activity’. Ethnic philosophy and, to a large extent, sage philosophy exemplify the former (the worldview in question being inspired by the divine, the ancestors or by the tribal elders). As Kenyan philosopher Reginald Oduor has put it, ‘ethnophilosophy ... sees African philosophy as the collective worldview of specific African ethnic groups’, while ‘sage philosophy ... comprises the thoughts of Africans who are not exposed to Western-type education, but are well versed in their own cultural backgrounds, and adopt a critical approach to their culture’ (Oduor 2012: 2).3 Similarly – at least to a certain extent – the postcolonial visions and ideologies of political leaders and liberation movement personalities (who were/are characteristically not academic or ‘trained’ philosophers) are examples of ‘philosophy as worldview’. However, while consisting largely of the adoption and adaptation of extant political ideology, nationalist-ideological philosophy contains ‘prescriptions of African politicians and intellectuals on strategies for the complete emancipation of Africa from the shackles of foreign domination’ (Oduor 2012) and, therefore, also moves into the terrain of critical (albeit very often philosophically unschooled) activity. It is characteristically with academic philosophy (which comprises ‘the writings of Africans who have [also] studied philosophy in Western ... or in Western-oriented universities in Africa or elsewhere’ (Oduor 2012: 2); see also Oruka 1990: 13ff.), at least to a greater extent, that there has been a noticeable trend towards critical activity, interrogation not only of the colonial intellectual ‘heritage’ but also of indigenous worldviews. We present the following table:

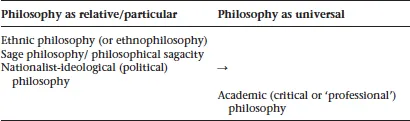

But who is to judge whether or not a particular mode of African philosophy meets the requirements for being defined as ‘philosophy’? At the heart of the debate about the nature of African philosophy is the controversy between cultural relativists (also referred to as particularists) and universalists. In essence, relativists (or particularists) argue that philosophy is part of culture and that African philosophy cannot reasonably be compared with philosophy from any other part of the world. In other words, there are no transcultural standards by which to judge one culture (or mode of philosophy) to be inferior or superior to another. On the other hand, the universalists assert that consistency in thought and action, valid and sound argumentation, logic and truth (and ideas like being, reality, causation, knowledge, belief, self and subjectivity, understanding, relationality/relationships, good and evil, right and wrong, etc.) transcend cultures, so that it should be possible to have a meaningful dialogue between African philosophy and philosophy from other parts of the world. Ethnophilosophy exemplifies an essentially relativist/particularist orientation, while academic philosophy constitutes a paradigm case of universalism. In a nutshell, relativists (or particularists) would insist that African philosophy is first and foremost African before it is philosophy. Universalists would maintain the opposite: African philosophy is first and foremost philosophy before it is African (see Oduor 2012). This can be illustrated in a third table:

Again, it is less easy to determine where sage philosophy and political (nationalistic-ideological) philosophy might be located. Because their respective concerns are chiefly with the local (cultural or national), it is tempting to associate them with relativism (or particularism) rather than with universalism – although political philosophy is certainly informed or inspired by ideas like human rights, universal franchise, global social justice and democracy.

The above discussion of the four major modes of philosophy in sub-Saharan Africa, specifically, and their positionality (with regard to worldview versus critical activity or to relativism/particularism versus universalism, etc.) will have a bearing on the central orientation of the book insofar as the ethical views expressed about nonhuman animals – their status and value – will characteristically be located in one or several of these modes of philosophical thought. Thus, the religious views, creation myths and discussions around rituals such as animal slaughter dealt with in Chapter 2, Chapter 3 and Chapter 4 are essentially connected with ethnophilosophy, while the traditional African perceptions of and interaction with the nonhuman world examined in Chapter 5 contain elements of both ethnic and sage philosophy. The ideas discussed in Chapter 6 and Chapter 7 – ubuntu, ukama, individualism, holism and relationalism – have their origins in ethnophilosophy but now constitute some of the most widely debated concepts in both nationalist-ideological and academic (critical or ‘professional’) philosophy. The discussion of animal welfare legislation and other legal ramifications in Chapter 8 is essentially aligned with the latter, academic philosophy, while some ‘mode-hopping’ takes place in Chapter 9. ‘Environmental justice’ is in the main a concept within recent academic philosophy, but it draws on elements, thoughts and beliefs already present in the other modes of African philosophy. Nonetheless, most of the views examined in this particular chapter are those held and advanced by professional philosophers from the African continent.

Central themes in African philosophy

Before I turn to religious and ethical views, with particular reference to animals and nonhuman nature, generally, it may be useful to identify some common themes in the work of African philosophers, past and present. The remainder of this chapter takes stock of trends and developments presented both at recent conferences and in recent publications on or within African philosophy (see Coetzee & Roux 1998, 2002; Odora Hoppers 2002; Wiredu 2004; Waghid 2014). According to Wiredu, philosophy is first and foremost a matter of effective thinking. To ‘think effectively’ means to have knowledge (wisdom and skills), to be tolerant and willing to enter into dialogue and to possess moral maturity (Wiredu 2004b: 17, 18). For Wiredu, this normative conception of effective thinking is inspired by the following: indigenous (African) knowledge systems (Wiredu 2004b: 24), traditional African faith in consensus (Wiredu 2004b: 21) and the conceptual and normative priority of community over individuality (Wiredu 2004b: 20). African philosophy, therefore, ‘must combine all these considerations, which ... reveal the strengths of the traditional African conception of education’ (Wiredu 2004b: 24). Wiredu, Oduor and others emphasise that the political liberation of African countries must be followed by intellectual liberation, that is ‘the emancipation of our thought’ (Oduor 2012: 4). The substratum for decolonisation of the African mind and for ‘creating an educational vision capable of serving the legitimate interests of Africa in the contemporary world’ (Wiredu 2004b: 24) is that Africans (learn to) think and/or philosophise in their own language. Wiredu’s notion of ‘decolonisation of the (African) mind’ as an important feature of philosophising on the African continent has been borrowed from Kenyan novelist Ngugi Wa Thiong’o. The idea is that conceptualisation, and thinking generally, is most effective if it is done in one’s own language.

In essence, then, prevalent themes have been the following:

•indigenous (African) knowledge systems;

•African communalism, ubuntu/botho/hunhu and consensus;

•the legacy of colonialism as well as political and intellectual emancipation;

•the ethical responsiveness of African philosophy.

I will discuss each of these and establish their relevance to concerns with the nonhuman world before gesturing towards an approach that arguably contains the possibility of Africa’s novel contribution to philosophy and in particular to thinking about the status and treatment of animals on the African continent.

Indigenous (African) knowledge systems

The motivation for a focus on indigenous (African) knowledge is fairly easy to explain, especially when one considers the denigration, suppression and exploitation of traditional knowledge systems during and even after colonialism. The reclamation project that underlies this renewed focus is not only epistemological but also concerned with legislation and social justice. As South African political philosopher Mogobe Ramose has put it:

The history of epistemicide in South Africa raises fundamental questions of justice such as the question of epistemological equality of all the existing paradigms of the peoples of South Africa. Epistemological equality is a vital ingredient in the construction of a truly representative South African identity expressed, among others, in the new South African philosophy of education. (Ramose 2004: 156)

It is clearly not difficult to be in principled agreement with what underlies many indigenous knowledge projects. First, the inferiorisation of indigenous peoples’ practices, skills and insights has, to a large extent, been arrogant and of questionable rationality. Second, current attempts by industrial and high-tech nations to (re)colonise or appropriate for commercial gain these practices, skills and insights are exploitative and contemptible.4 Finally, and most to the point of the central concern in this book, ‘Western’ or ‘Northern’ knowledge, science, technology and ‘rationality’ have led to, or have had as a significant goal, the subjugation of nature, and so far have been devastatingly efficient. The pursuit of nuclear energy, wholesale deforestation and destruction of flora and fauna, factory farming of nonhuman animals for human consumption, vivisection and genetic engineering are deplorable and – indeed – irrational (see Horsthemke 2010). In this regard, Tanzania-born Ladislaus Semali and Canadian Joe Kincheloe (both educational theorists) refer to the

use of indigenous knowledge to counter Western science’s destruction of the earth. Indigenous knowledge can facilitate this ambitious project because of its tendency ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction: Ethics on the African Continent

- 1 African Philosophy

- 2 Religion and Ethics in Africa

- 3 African Creation Myths and the Hierarchy of Beings

- 4 The African Ritual of Animal Slaughter

- 5 Traditional African Perceptions and Current Practices Taboos, Totemism and Spiritualism

- 6 Ubuntu/Botho/Hunhu and Nonhuman Animals

- 7 Ukama and African Environmentalism

- 8 Animals and the Law in East, West and Southern Africa

- 9 Environmental Justice

- 10 From Anthropocentrism towards a Non-Speciesist Africa

- Appendix

- Notes

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Animals and African Ethics by Kai Horsthemke in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Ethics & Moral Philosophy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.