eBook - ePub

Good Pharma

The Public-Health Model of the Mario Negri Institute

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Drawing on key concepts in sociology and management, this history describes a remarkable institute that has elevated medical research and worked out solutions to the troubling practices of commercial pharmaceutical research. Good Pharma is the answer to Goldacre's Bad Pharma: ethical research without commercial distortions.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Good Pharma by Donald W. Light,Antonio F. Maturo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Medical Theory, Practice & Reference. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Developing a Research Institute for Society

1

Origins and an American Vision for an Ethical, Independent Research Institute

When he was only 33, Silvio Garattini gave up a stellar career at the University of Milan as deputy chair and heir-apparent to the Department of Pharmacology to realize his vision of an independent pharmacological research institute, free of academic fiefdoms, stifling bureaucracies, and political or commercial influence, to develop better drugs for humanity. His strong, independent spirit and drive were developed during a childhood of hard work and self-sufficiency.

Born November 12, 1928, Silvio was the eldest of three sons who grew up in a humble home in Bergamo. Silvio’s father had become an orphan at an early age, losing his father to a heart attack and his mother to a broken heart. He had to raise himself, and Silvio said his father raised him and his brothers strictly. Even in elementary school, Silvio’s father reviewed his homework, and, if he thought it inadequate, he made Silvio do it again. He became Silvio’s most important role model. “He taught me to think critically, and not believe everything you see.”1

Silvio described his mother as quiet and sweet. She suffered from an early accident with scalding water that contributed to her becoming partly paralyzed and in constant pain. The boys were close and ran much of the household between them. In addition, one of his brothers contracted spondylitis when Silvio was 12 and became disabled. Spondylitis stiffens and inflames the disc spaces between the vertebrae, and his brother had to lie supine on a special bed to keep the vertebrae separate. Health insurance at that time only covered a limited number of visits; so Silvio’s father, who had a low-paying job at a bank, did the payroll for a local business in the evening for additional income to pay for the specialty care.

During World War II, Silvio was exempted from the army because his thorax was too thin; but, in 1944, his father was called to the military and asked his 16-year-old son to take over the work. “This gave me an early sense of organization and bookkeeping,” he said, the first foundation in a constellation of skills and experience on which he would draw for years to come.

When he turned 15 in 1943, Silvio and his parents talked constantly about which kind of school Silvio should attend next and decided that he should attend an industrial technical high school in Bergamo to acquire practical skills. Silvio took classes in the morning, especially industrial chemistry, and spent all afternoon doing labs, where instructors graded students on the precision of their assays. When he graduated at age 19 in 1947, Silvio received “the most important degree I got in my life.” Knowledge of chemistry and refined lab skills added two more foundations on which Garattini built his career. He could not find a job in chemistry, however, and earned his keep as an analyst at a steel factory. In this unwanted job, Silvio envisioned his future—medicine.

During this period, Silvio acquired a strong moral outlook that has shaped the Institute and the rest of his life. His father was anti-Fascist and did not want him to join Giovani Balilla, the Fascist youth movement. He was very thin and did not qualify for the military. When he was 14, Silvio joined the Azione Cattolica, the main Catholic association at the time, where he participated regularly in meetings and social activities in Bergamo. By the time he was 20, he became a regional manager of the student branch of Azione Cattolica and organized conferences, several about religion in contrast to the anticlericalism of Marxist groups, and he overcame his shyness through public speaking.

From these experiences, Silvio concluded that “You shall love your neighbor as yourself” is the most important commandment and the foundation for social ethics. One pillar standing on that foundation is human dignity and respect for each person, regardless of different individual qualities and characteristics. The sanctity of human life is inherent in the moral principle of human dignity. Human dignity calls for absolute honesty and the absence of malice or manipulation. One shall not cheat, manipulate, deceive, or deal falsely.

A second pillar is compassion and charity, especially for the poor, the sick, the suffering, and the dispossessed. One should do all one can to respond to unmet needs and to the calls from those in need, like the Good Samaritan who interrupted his journey to respond to a half-dying man and outcast.

A beam bolted across these two pillars is the principle of solidarity among others in the community and society and the pursuit of common good with them. Our responsibility toward one another is the foundation for human rights. This provides the basis for governments building institutions of common good, such as education and research.

Envisioning a future in medicine motivated Silvio to undertake a feat of will. Silvio’s graduation from the working-class industrial technical high school did not qualify him to apply to a university or to medical school, while graduates of Liceo Classico (classical high school where affluent children learned Greek and Latin) or Liceo Scientifico (math, physics, chemistry, and philosophy) could apply directly. To overcome this institutional form of class discrimination, Silvio needed a degree from a Lyceum, a three-year course he could not afford. So three months before the Lyceum exams, he quit his job, crammed in his room day and night, and passed. This collapsing of three years into three months enabled him to apply in 1948 to the medical school at the University of Milan, which accepted him. He found a part-time job as a secretary to cover living expenses while taking first-year classes.

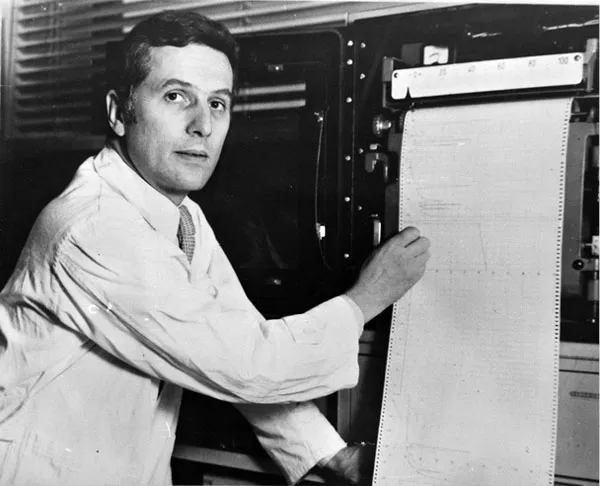

Photo 1.1 Silvio Garattini in Milan, age 35

In his third year of medical school, the course in pharmacology appealed as an area that drew on Silvio’s training in chemistry and lab work in ways that could enable him to help sick patients. The chairman of the department, Professor Emilio Trabucchi, asked for volunteers to give a lecture, and Silvio prepared one on antihistamines. “I took advantage of my chemical background. I could show different types of structures and demonstrate which groups showed activity. The professor was impressed and said, ‘Why don’t you come and work here?’ ”2 In this moment, Silvio’s disadvantage of attending an industrial technical high school turned into an advantage, because none of the more affluent and educated colleagues knew organic chemistry and its techniques for measurement. On several future occasions, Silvio drew on techniques used in industrial chemistry to pioneer their application and methods in medicine and pharmacology. With Professor Trabucchi, he began a research project on the kinetics of procaine or Novocain.

In 1953, Silvio gave a guest lecture at the Lombardy Academy of Science and Letters, where the professor of medicine assumed he was already a doctor. When he learned that Silvio was only a 24-year-old student and one he did not recognize as having taken his course (because he had not), he became irate and refused to grant Silvio access to the examination in clinical medicine. This prejudicial use of academic power and its professorial fiefdoms made a deep impression. Silvio was forced to transfer to the University of Turin to complete his MD degree in 1954, while commuting to continue his research with Professor Trabucchi.

Will and concentration, together with knowledge of organic chemistry and fine-grained measurement of chemical traces led Silvio to organize a small research team starting in 1952. He authored or coauthored about 10 articles a year in Italian medical and scientific journals—a new article every five weeks! He explained that they were short, not seriously refereed, and, of course, not read outside Italy. This led Silvio to recognize another dysfunction of Italian universities at the time: the ritual of producing articles bya marginal, self-referring circle of colleagues who cited each other’s work because they did not know English (nor often German or French) well enough to contribute to, or even keep up with important international developments in medicine and pharmacology. Silvio explained to us, “Articles in English were disqualified for advancement because Italian professors did not want to embarrass themselves for not knowing it.” With notable exceptions, the serious scientific world hardly knew of their existence. One might call this a guaranteed hierarchy of self-isolating obscurity.

A key feature of Silvio’s research that enabled him and his team to win grants and contracts centered on developing pharmacokinetics, based in part on techniques he transposed from organic chemistry. In 1953, he started using colorimetry and then added spectrofluorometry and gas chromatography at the end of the 1950s.

By 1955, Silvio earned a “Libera Docenza” or PhD in chemotherapy, and in 1958 another in pharmacology. He also received the Marzotto Prize in Medicine in 1954 for research on drugs for tuberculosis and the Prix de la Ville from Bergamo in 1955. The following year he received the prize from the Cariplo Bank. He was appointed as an assistant professor in the Department of Pharmacology, and in 1957 Professor Trabucchi de facto appointed him as the deputy chair of the department at age 29. “I worked day and night, and some nights I didn’t sleep at all,” he said. Meantime, Trabucchi became a Member of Parliament and spent much of his time in Rome, leaving Silvio to informally run the department and cope with the academic bureaucracy first hand.

The Bigger Picture

Why would a brilliant young scientist, chosen by a powerful patron and rapidly promoted to deputy chair and heir-apparent to an academic fiefdom, want to risk all to create a new institute independent of the public university system? The bigger picture was described by the distinguished medical sociologist Renée C. Fox, in a widely read 1962 article that the editors of Science took almost unchanged.3 It provided such a fine-grained analysis of obstacles faced by young scientists in Europe, especially after they had experienced the egalitarian atmosphere in the United States during a visiting fellowship, where what counted was fresh ideas and quality, not hierarchy and connections. Fox’s “Medical Scientists in a Château” created an international controversy and a deep rethinking about post–World War II research programs designed to restore Europe’s great scientific prowess, because it described how such programs were stymied by a country’s own institutional structures, rules, and customs. Fox wrote about medical research in Belgium; but much of it rang true for pharmacological research in Italy and other countries.

Fox began by describing the “sociologically encompassing” list of guests invited to a medical scientific colloquium. “The diversity and importance of extramedical influences on research and research careers is suggested by the presence . . . of political and religious personages, nobles, financiers, and patients and their families.” An ancient château was chosen as the site, and the invitation list strained for equality among the classes, factions, academies, societies, government departments, and institutes. Ritualistic attempts to create cross-cutting equality led to projects being “slow-moving, often delay-ridden, and sometimes indefinitely blocked.” For example, a major new hospital started 25 years earlier was not yet completed. Blockage or paralysis, in turn, led to finding circumventions, to using or creating petits chemins, and to the “complicated, time-consuming, never-ending process of writing eloquent, inquiring, imploring, demanding, grateful letters; of making formal and informal visits to strategic officials; and of sitting on numerous commissions.” Parties involved developed elaborate ways to meet competing demands of units or parties equitably, rather than rewarding scientific merit. The principal scientific commissions and councils were made up of senior professors who ruled over their fiefdoms, so that the research applications under review usually came from one of them, a self-perpetuating circle of an aging scientific elite who decided who among them would receive how much.

The château of the academy seemed to have a basement and a top floor, Fox suggested, with the middle floors nearly empty. The professor hires junior researchers to positions with low pay, little security, and basement status—and they are grateful for the patronage. Every decade or so, one of them might be elevated to the top floor. Belgian political parties, an observer wrote, “are equally consecrated to impotence. The necessity to act splinters all their divisions: in the face of this kind of peril [the need to act], without fail they put off until tomorrow what they could not settle today.” This influential account of post–World War II science in Belgium resonates with the frustrations of young scientists like Garattini in the 1950s.

Turning more specifically to Italy, the great sociologist of comparative education, Burton Clark, wrote a book that complements Garattini’s assessment of a career in academia, Academic Power in Italy: Bureau...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Foreword

- Preface and Acknowledgments

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction: Beneficence through Principled Research for Patients

- Part I: Developing a Research Institute for Society

- Part II: Reconceiving the Aims of Pharmacological Research

- Part III: Promoting Good Science for Better Medicines

- Appendix 1 Psychotropic Drugs: An Example of Mario Negri Research in the 1960s

- Appendix 2 Published Trials by the Mario Negri Institute since 2000

- Notes

- Index