![]()

P A R T I

The Demographic Transition and the Macroeconomy: Setting the Stage

![]()

C H A P T E R 1

Demographic Asymmetries and the Global Macroeconomy

José María Fanelli and Ramiro Albrieu

This chapter sets the stage for the analysis in the rest of the book. We provide empirical and conceptual background concerning international demographic asymmetries and examine the consequences for the distribution of the international labor force, global savings, and the growth dynamics of countries experiencing different demographic stages. We focus on the countries of the G-20 and, particularly, the four emerging economies selected for the country studies: Brazil, China, India, and South Africa (see chapters 6–9). Based on this evidence, we discuss the implications for global imbalances, capital flows, and the required expansion of the domestic financial system in emerging market economies. We interpret the implications in light of the financial and monetary distortions and flaws in the rules of the game that the global postcrisis scenario reveals.

The analysis utilizes the findings of the literature on demography and growth, international capital movements, and financial development in emerging countries to identify and discuss a number of stylized facts that motivated our research hypotheses and contextualize our research results and policy questions. We aim to characterize demographic-driven forces that will have a bearing on the evolution of the international economy in the coming two decades and that consequently call for national and global initiatives that can be included on current policy agendas. Particularly important for developing countries is the fact that many of them are now going through the demographic bonus phase; if the opportunities associated with such phase are not exploited, they will be lost forever. In line with that aim, we will work with a shorter time horizon than what is canonical in the demographic literature because it is more suitable for the types of macroeconomic and financial issues that we will address.1 In this regard, consider that one of the main hypotheses motivating the project was that certain domestic and international macroeconomic and financial dysfunctions can become stumbling blocks along the path of the demographic transition, impeding emerging and developed countries from taking advantage of the opportunities that the asynchronous path of the global demographic transition creates.

1.1 DEMOGRAPHIC ASYMMETRIES: LABOR, SAVINGS, AND GROWTH

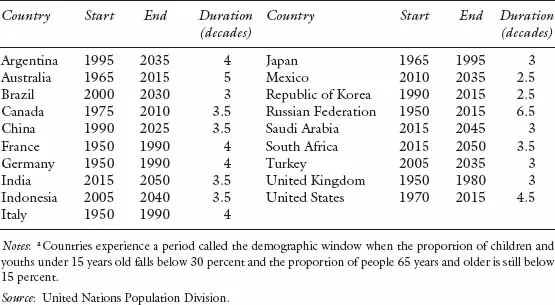

The global demographic dynamics reveals significant asymmetries across countries (Bryant, 2005). The concept of “the demographic window of opportunity” that we present in the introduction helps illustrate the existing and future evolution of demographic asymmetries. Applying this definition to G-20 countries and using United Nations (2013a) data yield the results shown in table 1.1.

Three facts stand out: the initiation year of the demographic window can differ substantially; developing countries enter this stage later than developed economies; and the duration of the demographic window is not constant across countries (United Nations, 2004). By the year 2100 the demographic transition will have ended (Lee, 2003). European countries entered the demographic window before Canada, the United States, and Japan. Emerging economies are either “children” (e.g., India and South Africa) or going through the demographic window (e.g., Argentina and Indonesia). Among rich countries, shorter windows (from two to three decades) correspond to Japan and the United Kingdom. Australia and the United States are ending longer windows (from five to six decades). In the case of emerging countries, the shorter windows are expected to occur in Mexico, Korea, Brazil, and Turkey and longer windows in Russia. With the exception of Russia, the duration of the demographic window in emerging economies appears to replicate the Japanese experience.

Table 1.1 The demographic window in G-20 countriesa

Global Reallocation of the Labor Force

Despite the asynchronous path of the demographic transition, the world is ageing. According to United Nations estimates, by 2030 the old age population (those above 65 years old) will have reached 12 percent of the total population, that is, nearly one billion people (United Nations, 2013a). Furthermore, ageing will accelerate over the coming years compared to previous dynamics (e.g., 1990–2010).

The old age population currently represents about 17 percent of the total population in advanced economies, but in 2030 it will have grown to about 24 percent. The situation in emerging economies is different: the working-age population is expected to maintain its share in total population in the future. A key consequence of the conjunction of asynchronies in the demographic path and global ageing is that the distribution of the world’s total labor force across countries is changing (see figure 1.1).

Although the characterization of advanced economies as the “old world” and emerging ones as the “young world” certainly reflect the current situation, we should not overlook the fact that important within-group asymmetries exist in advanced as well as emerging economies (see figure 1.2, and Wilson and Ahmed, 2010). The share of the working-age population in countries in the first group, such as Japan and Italy, peaked in the early 1990s; in France and Germany in the mid-1980s; and in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia in the late 2000s. We also see differences among the (future) peaks in the emerging economies’ working-age population. In South Africa and India the working-age population’s share is expected to peak in the 2040s, in Argentina and Brazil in the late 2010s, and in China in 2014. Differences are also foreseen in the speed of adjustment after the peak, with some countries (such as China and Brazil) expected to age at a faster pace than...