- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Remaking of the Mining Industry

About this book

The industrialisation of China prompted the biggest commodity boom of modern times. Soaring prices gave rise to talk of a commodity super cycle and induced a wave of resource nationalism. The author, who was chief economist at two of the world's largest mining companies, describes how this resulted in a transformation of the global mining industry.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Remaking of the Mining Industry by D. Humphreys in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Barren Years

Are they still doing that?

It was the autumn of 1999, and Hugh Morgan, the forthright head of Western Mining Corporation, was entering the United Kingdom to deliver an address at the London Metal Exchange (LME) dinner, one of the biggest events in the global corporate calendar. In response to an immigration officer’s enquiry regarding his occupation, he replied that he worked in the mining industry. The officer eyed him quizzically and asked, ‘Are they still doing that?’1

The theme of Hugh Morgan’s address that evening was the contribution that technology could make to improve productivity in mining. However, this was not the sort of technology the world was then interested in. The sort of technology that was grabbing the public’s imagination was ICT, information and communications technology, more specifically the fast-expanding Internet and World Wide Web. In what became known as the ‘dotcom’ bubble, the index of the NASDAQ, the US stock exchange specialising in technology stocks, soared to a peak of 5049 in early March 2000, more than double its level a year before. Meanwhile, mining stocks languished, unwanted and unloved. The industry was deeply unprofitable, and its future looked bleak. Between 1995 and 2000, mining’s share of global stock market values declined from 5 per cent to 1 per cent. In 1999, the entire quoted global mining industry had a market capitalisation of around $300 billion. In December of that year, the value of one technology company, Microsoft, was double that, $620 billion. This did not bode well for the industry entering the new millennium. The public commonly perceived the industry as dark, dirty and dangerous, certainly no place for the young and ambitious.

Disappearing demand

Several factors contributed to the dire condition of the mining industry at this time.

The first factor was the trajectory of global economic growth. The demand for mineral raw materials is highly sensitive to the rate of economic growth and to changes in the rate of growth. The global economy had rattled along fitfully through the 1950s to the 1970s, supported by a vibrant US economy and the post-war reconstruction of Europe and Japan. However, from the 1970s, things slowed up radically. Over the period 1950–1975, global GDP (Gross Domestic Product) had achieved an average growth rate of 4.8 per cent a year. Through 1975–2000, it managed just 3.0 per cent.2

There were two key reasons for the slowing of global growth. The first reason was the deep economic recession that followed the oil crisis of the late 1970s. This was in part caused by the tight monetary policies applied at the start of the 1980s to squeeze inflation out of Western economies. The second reason was the economic slowdown and eventual collapse of the Soviet Union. Between 1990 and 2000, the economies of the former Soviet Union (FSU) shrank in size by over a third.3 Both these developments had a severe negative impact on global demand for minerals.

There was, however, a bit more to it than this. Along with the slowing in the rate of economic growth, changes were taking place in the nature of that growth. As Western economies emerged from the period of post-war reconstruction, their growth was becoming less material intensive. This partly reflected the fact that the focus of growth was shifting away from investment towards consumption. Investment as a percentage of GDP (expenditure based) in Japan had peaked at 36 per cent in 1973. By 2000, the share had fallen to 26 per cent. At the same time, the focus of consumption in Western industrial economies was shifting from the production of things to the provision of services. In 1980, the share of services in Japan’s GDP (output based) was 58 per cent; by 2012, it had risen to 73 per cent. The equivalent figures for the United States were 64 per cent and 79 per cent.4 The share of manufacturing in these economies displayed a corresponding decline. Growth, in short, was moving to activities which simply used less stuff.

In addition to these changes in the composition of growth, products were themselves becoming less material intensive. Copper tube used for plumbing was being produced with narrower gauges and thinner walls, thereby reducing the amount of copper required to produce it. Miniaturisation was cutting into the market for copper wire. Improvements in electro-galvanising meant that galvanised steel could be produced with thinner coatings of zinc. Lead was being phased out of use in petrol as an anti-knock agent. In response to the oil shocks of the 1970s, drivers in the 1980s switched to buying smaller cars, reducing the amount of steel they used. The development of higher quality alloy steels was resulting in the light-weighting of architectural structures.

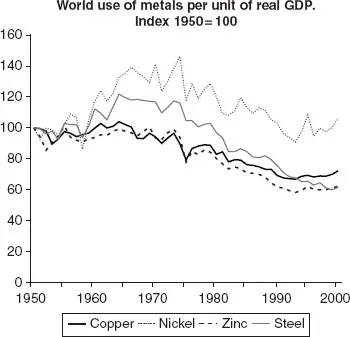

As a consequence of these two trends – the declining product intensity of GDP and the declining material intensity of products5 – demand for many mineral commodities was being eroded. ‘Intensity of use’, a concept used by economists to measure the amount of a commodity employed for each unit of GDP, appeared to be in long-term decline. Between 1970 and 2000, the intensity of use of nickel declined by 25 per cent and that of steel by 47 per cent (see Figure 1.1).

According to some observers, this ‘dematerialisation’ of economic activity was the pattern for the future. The smokestack industries of the old economy were giving way to a digital ‘new economy’. The central idea of the new economy was that the generation and exploitation of knowledge were going to play an ever-increasing part in the creation of wealth. The fundamental natural resources in this world were not things dug out of the ground but human creativity and intelligence. Wealth would increasingly be embodied in intellectual property rather than in things you could drop on your foot. The vehicles for this knowledge were microchips, computer software, digital data transmission, multimedia and mobile telephony. Moreover, it had a particular property – it was increasingly ‘weightless’.

Figure 1.1 Intensity of use of selected metals, 1950–2000

Source: Maddison (2006), IMF, Metallgesellschaft, WSA.

One of the exponents of the ‘weightless economy’ explained it thus:

During the past half century or so, technological and economic changes have meant that we produce things of much less bulk: transistors rather than vacuum tubes, fibre-optic cables or satellite broadcasting rather than copper wire, plastics rather than metals. Materials have changed and miniaturisation has been pervasive. … The value in our economy – whatever it is we are prepared to pay money for – has less and less physical mass. Whether it is software code, genetic codes, the creative content of a film or piece of music, the design of a new pair of sunglasses or the vigilance of a security guard or helpfulness of a shop assistant, value no longer lies in three-dimensional objects in space. We will pay for amusement, for style, for convenience, for speed, for creativity, for beauty – but when it comes to things, commodities, we have turned into skinflints, and want the cheapest possible.6

While there was clearly something in this argument, it was a very partial perspective. It overlooked, for example, the investment in basic materials which the digital economy required for the fabrication of computers, switchgear, routers and servers, and the power stations, fuels and transmission networks required to keep them running. Power brownouts in California, the heart of the new economy, during 2000 and 2001, revealed that some of the new technology plants were consuming the power of small cities. Also, it ignored the structural fabric of the weightless economy. The new economy did not exist in the ether but was housed in offices, trading floors, shopping malls, multiplexes and homes, all of which required substantial amounts of materials for their construction. Those made rich by the dotcom boom were ploughing their money back into bigger, power-hungry homes and newly built health clubs and resorts.7 Between 1985 and 1998, the copper intensity of the average US home increased from 0.63 kilograms per square metre to 1.02 kilograms per square metre according to the Copper Development Association.

More importantly, it was very much an advanced economy perspective. It took little account of the billions of people around the world who did not have the material possessions and facilities enjoyed by those living in the advanced economies. Many of these people were very interested indeed in material intensive products such as houses, refrigerators and cars. At the time, two-thirds of the world’s population did not have access to a telephone and one-third did not have electricity. It was true that Western economies had in the past dominated the global economy and, along with this, the consumption of mineral raw materials. Even in the late 1990s, when the above-mentioned quotation was being penned, they still accounted for around two-thirds of the global consumption of metals. But this was beginning to change – and change dramatically.

Too much of everything

The process of dematerialisation identified by the exponents of the weightless economy posed a major dilemma for companies in the mining industry, an industry whose future depended on continuing growth in demand for material products.

The industry was slow to grasp the significance of the oil shocks and of the economic recession that followed in 1980–1982. The general presumption was that this was a hiccup, and that once it had passed, the rates of growth which had preceded the crisis would resume. Accordingly, companies retained capacity which was surplus to requirement rather than close it down permanently and remained open to the idea of investment in mines which might be needed as and when the recovery of demand finally arrived.

This belief that demand growth would, in time, pick up to something close to pre-oil crisis rates found support in academic and government research. One such piece of research, published in 1983, was carried out by the Institute for Economic Analysis (IEA) at New York University under the direction of Nobel Laureate, Wassily Leontief. Using the input–output technique which Leontief had pioneered, the study made a series of projections for the demand for mineral raw materials to the year 2030.8 For the period 1970–2000, it projected annual average growth in world demand for copper, nickel and zinc, at 4.4 per cent, 2.7 per cent and 3.5 per cent, respectively. This compared with actual rates of growth for copper, nickel and zinc demand over the period 1950–1980 of 3.9 per cent, 5.1 per cent and 3.7 per cent. In other words, the IEA was projecting a rate of growth in demand for copper which was slightly above the recent historical experience, a rate for nickel which was somewhat below and a rate for zinc which was pretty much in line. Nickel aside, the impression conveyed by these projections was one of continuity. In similar vein, the US government agency, the US Bureau of Mines, was at this time projecting annual growth in demand over the period 1970–2000 at 3.9 per cent for copper, 4.3 per cent for nickel and 2.1 per cent for zinc.9

Against this backdrop, it was not so surprising that, as the global economy started to recover in 1983, the industry determined that normal service had once more resumed and opened the taps on production. It was too much, too soon. Although global copper demand turned positive in 1983 and 1984, the market was overwhelmed by new supply. Stocks of copper on the metal exchanges of New York and London, which had collectively stood at 300,000 tonnes in early 1982, soared to over 800,000 tonnes by the end of 1983. Prices over the same period slid from $1600/tonne (73c/lb) to around $1400/tonne (64c/lb). Although greater restraint by copper producers meant that stocks declined thereafter, and kept on declining, it wasn’t until the second half of 1987 – nearly four long years later – that the copper price finally began to stage any sort of recovery.

The condition of the iron ore market at this time was, if anything, even worse. The vast iron ore deposits of the Pilbara in Western Australia had been opened up during the 1960s to meet rising demand from Japan’s fast-growing steel industry. Between the early 1950s and 1973, Japanese steel production grew at over 15 per cent a year. Lacking any iron ore resources of its own, this gave rise to a burgeoning demand for seaborne iron ore. However, with the oil shocks in the 1970s, Japan’s growth in steel production came to an abrupt halt, and so too did its requirement for increased tonnages of imported iron ore. Having reached a peak of 119 million tonnes in 1973, Japan’s annual steel output slipped back into the range 100–110 million tonnes, where it remained for the next 20 years. Mine projects which had been committed on the assumption that the earlier higher rates of growth would persist, found they had nowhere to place their product.

Adding to the problems of oversupply in the industry, Brazil was in the process of making a substantial addition to world iron ore supply. Vast deposits of high-quality iron ore had been discovered in the Amazon Basin in the 1960s, and plans were developed by the state company Companhia Vale do Rio Doce (CVRD) to build what would become the world’s largest iron ore mine at Carajás. In 1978, work started on the 890 kilometre railway that would bring the iron ore out of Carajás to the coast at Ponta da Madeira from where it could be shipped. By 1985, work on the mine and the associated infrastructure was complete and production at the mine commenced.

The timing of Carajás could scarcely have been worse from the perspective of the global market balance. Although the target of Brazil’s iron ore sales at this time was Europe rather than Japan and the Asian market, the European steel industry was in no better condition to absorb large additional quantities of iron ore than was Japan. Having peaked at 156 million tonnes in 1972, steel production in the European Community had slumped to 128 million tonnes by 1980 and the industry was operating with a capacity utilisation rate of only 60 per cent.10

The world was simply awash with iron ore, and prices reflected this. The seaborne iron ore market had its own distinctive way of establishing prices. Typically, the Australian iron ore producers negotiated with leading Japanese steel mills while Brazilian and Canadian producers negotiated with leading European steel mills. By convention, the price of the first settlement was adopted as the ‘benchmark’ price by buyers and sellers in both Pacific and Atlantic markets for the following year’s shipments.

Between 1982 and 1988, the benchmark price of seaborne iron ore fell every year, ending 32 per cent below its starting point. Observing his port disappearing under mountains of unwanted iron ore stocks, one senior Australian manager lamented, ‘You can’t eat iron ore’. During the negotiations on 1987 prices, the Japanese steel mills alleged that one of the main Australian producers, Hamersley Iron, was trying to stem the fall in prices by orchestrating a coordinated producer response, in contravention of competition law. Accordingly, the Japanese mills that year rewarded Hamersley’s principal competitor, BHP, with additional contract tonnages, albeit at a 5 per cent reduction in price. The irony of the fact that the steel mills in Europe and Japan openly coordinated their stances in contract negotiations was apparently lost on the buyers.

The North American iron ore market was in no better condition than those in Asia and Europe. Having substantial resources of iron ore in the northern states (Minnesota and Michigan) and across the border in Canada, US steel producers had no need for supplies from the seaborne market. However, declining steel demand was diminishing the need for local iron ore among steel makers around the Great Lakes. In addition, the position of the large integrated steel mills using blast furnaces and iron ore was being challenged by the development of small producers using electric arc furnaces (EAFs) and steel scrap as feed. The availability of scrap and power being the most important inputs for these producers, they were able to locate themselves away from the traditional steel-producing areas. Not requiring the infrastructure and scale of integrated steel plants, and being free of the constraints of using unionised labour and the crushing pension obligations of the major steel producers such as US Steel and Bethlehem Steel, these EAF producers were inherently lower cost than their larger brethren. In consequence, North American producers of iron ore suffered badly, the largest of them, Cleveland Cliffs, being pushed to the brink of bankruptcy and into a debt restructuring programme in 1987.

Although mineral commodity markets rallied towards the end of the 1980s, the pattern had nonetheless been set for a number of years to come, and by the early 1990s, the industry was once more grappling with conditions of weak prices and chronic oversupply. Miners continued to produce and invest for a higher level of demand than was required. Any upturns in the industry’s prospects were quickly overwhelmed by new supply. Although industry leaders frequently remarked that this situation could not go on and that sooner or later prices would have to rise to levels which provided some sort of return on capital if companies were to have an incentive to invest, by using such ‘incentive’ prices for the purposes of evaluating their projects they were helping to ensure that the higher prices never arrived. The tendency to use unrealistically high prices in their project assessments can probably be attributed in part to the stubborn optimism of the mining industry, while the tendency to overproduce may have owed something, at least for some commodities such as iron ore and nickel, to a destructive pursuit of market share among producers. It also seems likely that a part was played by ‘social production’, that is to say, production from operations, often under state ownership, which was kept operating in order to preserve employment or flows of foreign currency. Whatever the reasons, it was a condition one CEO graphically described as ‘supply incontinence’.

A final challenge for the mining industry during these years arose from the collapse of the Soviet Union. As one of the two great global powers during the Cold War, the Soviet Union was a major producer and consumer of mineral commodities. In 1970, the Soviet Union was the world’s largest producer of iron ore and platinum group metals and the ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Acknowledgements

- About the Author

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1. The Barren Years

- 2. China Changes Everything

- 3. Feeding the Dragon

- 4. Prices Take Wing

- 5. An Industry Transformed

- 6. Enter the Emergers

- 7. Dividing the Spoils

- 8. Consumer Concerns

- 9. The Next Thirty Years

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography and Data Sources

- Index