eBook - ePub

Democratic Participation in Armed Conflict

Military Involvement in Kosovo, Afghanistan, and Iraq

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Democratic Participation in Armed Conflict

Military Involvement in Kosovo, Afghanistan, and Iraq

About this book

Under which conditions do democracies participate in war, and when do they abstain? Providing a unique theoretical framework, Mello identifies pathways of war involvement and abstention across thirty democracies, investigating the wars in Kosovo, Afghanistan and Iraq.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Democratic Participation in Armed Conflict by Kenneth A. Loparo,Patrick A. Mello in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & International Relations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

Compared to the amount of research devoted to the interdemocratic peace proposition, the “flipside” of democratic participation in armed conflict has received considerably less attention. Moreover, due to a widespread focus on regime type differences, many studies in International Relations (IR) implicitly treat democratic regimes as a homogeneous group and thus fail to account for substantial variation within the group of democracies. While scholars have persuasively made the case that “democracy” needs to be unpacked to be meaningful (Elman, 2000), this remains rarely done in the field of international politics and conflict research. In Comparative Politics, on the other hand, research on democratic subtypes and their virtues and weaknesses abounds, but this knowledge is seldom applied to matters of security policy.

In this book, I investigate the conditions under which democracies participate in armed conflict. Based on the premise that substantial variation exists among democratic systems and that this variation might account toward an explanation for democracies’ external conflict behavior, relevant institutional and political differences are identified across contemporary democracies. My integrative theoretical approach highlights the importance of domestic factors, such as partisan politics, executive–legislative relations, constitutional differences and public opinion but further takes into account systemic factors, such as a country’s relative power status.

This study resonates with a renewed emphasis on the link between domestic politics and international relations. While IR scholars have long neglected domestic politics in favor of systemic variables, it is by now widely acknowledged that domestic factors and international relations are highly inter-connected and that a focus on the former can enhance the understanding of the latter (Gourevitch, 2002: 309). In this context, a number of publications have initiated what may constitute a “democratic turn” in security studies (Geis and Wagner, 2011). Works in this vein have broadened the democratic peace research program by focusing on the conditions under which democracies use military force, democracy’s inherent ambiguities, and the differences between democratic states regarding their constitutional structure, domestic institutions, political culture, and partisan politics.1 Yet the insights of these works have only sparsely made their way into comparative studies.

Against this backdrop, three general questions arise, concerning the domestic sources of democratic foreign policy and the interaction of domestic and international factors in relation to conflict behavior. First, when do domestic institutions constrain or enable government use of force? Previous research has conceptualized “institutional constraints” in various ways, ranging from abstract considerations of the democratic process, to the prospect of electoral backlash and concrete veto opportunities that arise in distinct political constellations. At the same time, it has been suggested that democracies are somehow able to alter their behavior when faced with non-democracies, sidestepping existing institutional constraints and “the due political process” (Maoz and Russett, 1993: 626; Russett, 1993: 38–40). This underlines the need to investigate more specific forms of institutional constraints such as parliamentary veto rights and constitutional restrictions on the use of force and the conditions under which these become effective. Second, to what extent do partisanship and public opinion matter in military deployment decisions? The traditional (realist) perspective suggests that “politics stops at the waters’ edge” (Gowa, 1998); thus, we should expect a foreign policy consensus between political parties on decisions over war and peace. This conception seems to be misguided, however, since studies have repeatedly demonstrated partisan divides on security issues. Relatedly, the role of public opinion in foreign policy decision-making remains heavily contested. While proponents of liberal arguments suggest that democracies are constrained by public opinion, others hold that democratic leaders are hardly affected by public opinion in their decision-making, even when substantial parts of the citizenry oppose a military commitment. Third, how do international organizational frameworks influence democracies’ participation in military operations? It seems plausible to assume that the organizational auspices under which an operation is run affect government decisions, that is, whether missions are carried out through the United Nations, by regional organizations such as the European Union (EU) or the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), or in ad hoc coalition frameworks. Since the latter have become increasingly common for enforcement operations, an investigation into the conditions that foster the participation in ad hoc coalition frameworks should be a pressing concern.

Recent studies have suggested promising explanations of democratic conflict behavior, but the question of how to conceptualize military participation remains. What kind of contribution counts as war involvement? Does it suffice if a country provides logistical support to an operation or should only the large-scale deployment of combat forces be considered military participation? To which extent is the timing of a military deployment relevant? In this book, I address these questions in the specific historical context of the wars in Kosovo, Afghanistan, and Iraq. Based on a comparative framework that includes 30 democracies and five causal conditions, I offer an integrative theoretical explanation for military involvement and non-involvement in each of these conflicts.

The central argument of this book consists of three propositions. First, I argue that many generalizations about democracy obscure rather than help further our understanding of international politics. While the democratic peace research program has yielded a host of empirical observations and valuable insights about the conflict behavior of democracies and non-democracies, it has also reified the dividing line between these regime types. The result is that important sources of intra-democratic variance often get overlooked, which could partially explain why scholars report conflicting findings on the relationship between regime type and conflict behavior (cf. Mintz, 2005: 5). The second claim flows from the first: variation among democracies needs to be taken more seriously. Though scholars have paid lip service to the mutual benefit of an increased awareness of each other’s work in the subfields of International Relations and Comparative Politics, few studies in conflict research have taken aboard richer conceptions of democracy. In fact, most studies base their conceptualization of democracy on lean models that do not take into account the institutional variety across Western democracies, much less the diversity that characterizes non-Western countries. Finally, I argue that our notions of democratic war involvement need to be brought in line with the nature of contemporary armed conflict and reconnected to processes of political decision-making. The democratic peace research program has relied, for the most part, on what constitutes an anachronistic conception of war involvement. Hence, frequently used measures of military participation tend to be far removed from the actual deployments made. However, in order to gain confidence about the conditions that lead toward war involvement and abstention, we also require a more fine-grained qualitative assessment of democratic war participation in the historical context of a given conflict.

The remainder of this introductory chapter introduces the book’s research design, including definitions of key concepts and a detailed discussion of the criteria that guided the case selection for the conflicts and countries examined. The final section provides a concise book outline.

Research design

This book investigates democratic war involvement. Conceived primarily as a comparative study, a two-fold emphasis is placed on exploring institutional and political sources of variation across consolidated democracies and examining their participation in armed conflict. Given these aims, the research design combines a comparative perspective on an intermediate number of democracies with a focus on three contemporary cases of armed conflict. The remainder of this section defines the book’s conception of military participation and relates it to existing definitions of similar terms. This is followed by an explication of the criteria that guided the case selection, both in terms of armed conflicts and for the democracies included in this study.

Defining participation in multilateral military operations

For the purposes of the present study, I define military participation as the deployment of combat-ready, regular military forces across international borders to engage in the use of force inside or against a target country as part of a multilateral military operation.

This definition comprises several components that delineate the universe of cases. First, it entails a range of military operations where units are authorized to use force, from humanitarian military intervention to peace enforcement operations and interstate war. At the same time, it excludes traditional peacekeeping missions, where the use of force is restricted to purposes of self-defense. Second, the definition covers various kinds of military deployments, including ground, air and naval units, but these must be directed at a regime or against non-state actors within a country. Hence, the definition discounts involvement in naval operations, such as anti-piracy missions. It further focuses on the deployment of regular forces to ensure comparability, which eliminates the contracting of private military and security companies.2 Finally, this study concentrates on multilateral military operations, because unilateral engagements, by definition, preclude within-case comparisons across countries. Multilateralism is understood here in a minimal sense as coordination between “three or more states, through ad hoc arrangements or by means of institutions” (Keohane, 1990: 731).3 Hence the definition applies to ad hoc coalitions as well as military operations under the auspices of international organizations.

My conception of military participation relates to established definitions of military intervention.4 Unlike some prior studies, however, I do not differentiate war from military intervention for my case selection or for analytical purposes. As other authors acknowledge, there is a substantial gray area between military intervention and war (Finnemore, 2003: 9). This ambiguity puts into question the analytical value of the distinction between these two concepts. In legal terms, both military intervention and war constitute armed conflicts. However, a distinction should be made on the grounds of whether or not a case falls under one of the two stated exceptions to the general prohibition on the use of force under Article 2 (4) of the UN Charter. These entail individual or collective self-defense, based on Article 51, and the use of force under authorization from the Security Council, in accordance with Chapter VII of the UN Charter (Greenwood, 2008: 1). In political terms, the distinction between military intervention and war traditionally serves to separate action on behalf of a regime or a powerful faction within a country from conflict between two or more sovereign states (Bennett, 1999: 14; Levite et al., 1992: 5). This view sees military intervention as directed toward “changing or preserving the structure of political authority in the target society” (Rosenau, 1969: 161), whereas interstate war is held to primarily serve the aim of territorial conquest (Levite et al., 1992: 6).

These distinctions notwithstanding, complications arise when trying to categorize particular historical cases. For instance, the Persian Gulf War that began with Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990 has been termed “fundamentally an interstate war” because the US-led multinational coalition had the objective “to restore internationally recognized territorial boundaries” (Levite et al., 1992). At the same time, scholars have classified the Gulf War as a military intervention to acknowledge the fact that an outside power intervened on behalf of the regime in Kuwait (Kreps, 2011: 15, 51; Saunders, 2011: 15, 22). To take another example, the American engagement in Vietnam began in 1950 as military assistance to the French and later to the South Vietnamese government, but this support incrementally turned into a military intervention and by 1965 it had escalated into full-scale war (Krepinevich, 1988: 258–275). These two cases illustrate that the search for a sharp dividing line between war and military intervention is fraught with difficulties, if not illusory. Hence, for the purposes of this book, I apply the inclusive definition of military participation stated above. With regard to the observed conflicts and the outcome to be explained this allows for variation within well-defined limits.

Case selection

The comparative design of this study essentially requires two case selection decisions. The first concerns the armed conflicts to be investigated, which are drawn from the universe of cases circumscribed by my definition of military participation. The second decision relates to the democracies that ought to be considered potential military participators in the selected conflicts. I address each in turn.

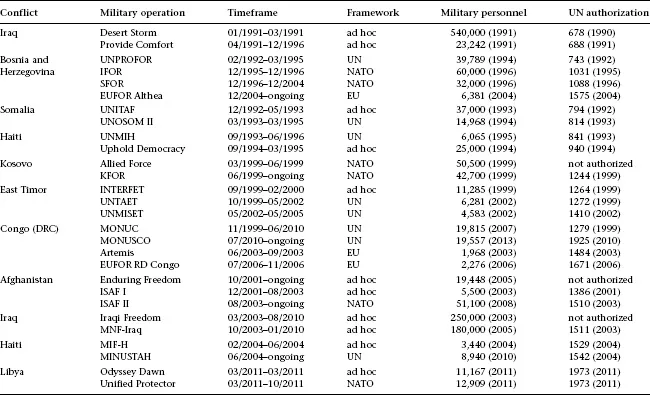

With regard to armed conflicts, the book’s inclusive definition of military participation yields a fairly large number of potential cases. Hence, for case selection purposes, three scope conditions are applied to narrow down the population and to enhance comparability. First, the observed timeframe is restricted to the post-Cold War period (1990–2011). This way systemic factors are held largely constant. Second, conflicts are only included if they contain at least one military operation with personnel equal to or above 5,000 soldiers.5 Finally, in order to be considered for case selection, several Western democracies need to have made sizable military contributions to a given conflict. This criterion eliminates many UN peace support operations, where non-Western countries are often the major troop contributors.6 Given these scope conditions, the universe of cases consists of 11 armed conflicts and 28 military operations. These are listed in Table 1.1.

Of the potential case studies, the book investigates democratic participation and non-participation in the wars in Kosovo, Afghanistan, and Iraq. These cases were selected for several reasons. First, the three conflicts are among the most extensive uses of force by democracies in the post-Cold War era, both in terms of combat intensity and the duration of the multilateral military engagement, if one includes operations that followed upon the initial invasion. This makes them particularly interesting cases for study.7 Second, each conflict reached a certain issue salience and was surrounded by substantial political conflict and public contestation across Western democracies.8 Thus, if approaches that emphasize partisanship or public opinion have any explanatory value, then they should apply to these cases. Finally, democratic governments have shown substantial variance in their responses to these conflicts. While some countries became involved militarily in all three cases, several governments abstained entirely and still others made selective deployments. At the same time, the conflicts in Kosovo, Afghanistan, and Iraq vary with respect to their political legitimation, legality in international law, the involvement of international organizations, and the intensity of armed conflict, which enhances their inferential value from a comparative perspective.

Table 1.1 Case selection: Armed conflicts

Note: The aerial operations in Kosovo and Libya comprised 29,000 and 26,500 sorties, respectively. UN authorization indicates the initial Security Council resolution for each mission, excluding mandate renewals or alterations.

Sources: IISS, ‘The Military Balance’ (various yearbooks), SIPRI ‘Multilateral Peace Missions database’ (www.sipri.org), SIPRI, ‘Armaments, Disarmament and International Security’ (various yearbooks), UN Security Council documents (www.un.org).

One might object that the selected cases are too dissimilar for comparative purposes. However, this study focuses primarily on comparing democracies’ responses within each case. Only in the final chapter is the attempt made to compare across conflicts and to draw out similarities and generalizable patterns. The Kosovo case set a precedent as a military operation under NATO auspices ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Democracy and War Involvement

- 3 Explaining Democratic Participation in Armed Conflict

- 4 Fuzzy-Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis

- 5 Kosovo: Forced Allies or Willing Contributors?

- 6 Afghanistan: Unconditional Support but Selective Engagement?

- 7 Iraq: Parliamentary Peace or Partisan Politics?

- 8 Democracies and the Wars in Kosovo, Afghanistan, and Iraq

- Appendix

- Notes

- References

- Index