Introduction

My relating theory, previously called spatial theory, began to take shape in the late 1980s. At that time I had conversations with both the established attachment theorist John Bowlby and the researcher John Wing. John Bowlby had proposed the dimension of attachment versus detachment and John Wing had proposed the dimension of dependence versus independence. Bowlby was opposed to Wing’s concept of dependence, but I could see the value of both these classificatory systems. However, I preferred to compress the terminology of relating behaviour even further into the simple terms of ‘close versus distant’ (on the horizontal axis) and ‘upper versus lower’ (on the vertical axis). This had the effect of organising a person’s relating behaviour within a spatial framework so that the concept of people relating across space became central to my conceptualisation of how people relate to others and are related to by others, and this system began to be recognised by others in the 1990s. In 1991, Professor Russell Gardner wrote, ‘Dr Birtchnell’s spatial schema has considerable potential for analysing data on interpersonal relationships’ and in 1993 Professor Aaron Beck wrote an endorsement for the cover of my book How Humans Relate: A New Interpersonal Theory (Praeger) which stated ‘I am convinced that John Birtchnell is on to something important in terms of his vertical and horizontal axes.’ A number of other distinguished academics such as Professor Paul Gilbert also commended my theory in the foreword of the aforementioned book, and others (Trent 1994; Reichelt 1994) provided excellent reviews of it.

It was Maurice Lorr (personal communication 1987) who first brought to my attention the resemblance of my relating theory to interpersonal theory, a theory which he himself had helped to develop (Lorr and McNair 1963), and I have since sought to explain the similarities and differences between my theory and interpersonal theory (Birtchnell 1990, 1994, 2014; Birtchnell and Shine 2000; see also Chap. 2 of this volume).

I am not the only person to think in terms of the horizontal and the vertical axes. Hartup (1989) observed that vertical relationships emerge during the first year of life and provide protection by the parent for the infant. Horizontal relationships are essentially child–child relationships and are evident only in rudimentary form until about the third year of life. Thereafter they are increasingly common.

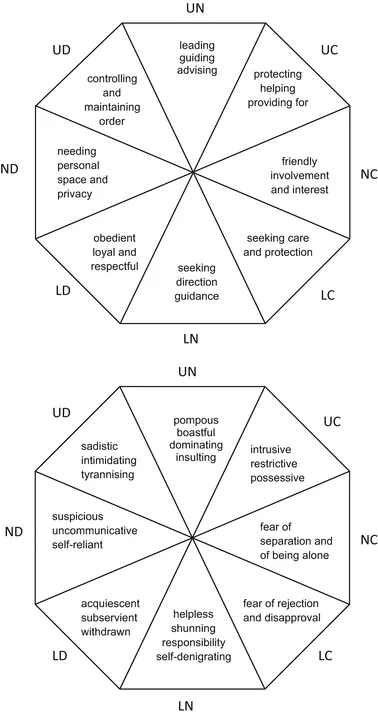

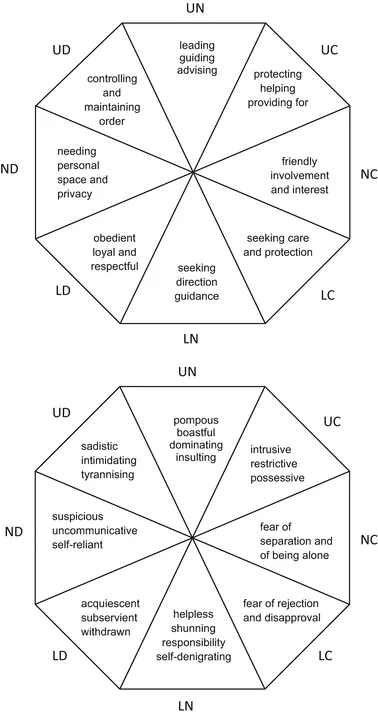

Relating theory is fully described in my three books on this topic: How Humans Relate: A New Interpersonal Theory, Relating in Psychotherapy: The Application of a New Theory and The Two of Me: The Relational Outer Me and the Emotional Inner Me (Birtchnell 1993/1996, 1999/2002, 2003, respectively). The present chapter is an updated summary of the theory. Because it is preoccupied with the interactions that occur between people across space, and because it is constructed around the vertical and the horizontal axes which intersect each other, it is sometimes referred to as spatial theory. However involved people may become with each other, each person will always remain a separate individual. We sometimes use terms such as ‘I feel close to you’ or ‘you feel distant from me’ or ‘I look up to you’ or ‘You look down upon me’, suggesting that, at some level, people quite often actually do experience relating in spatial terms. An important point to be made at this juncture is that each of the two axes serves a separate set of functions: the horizontal one is concerned with degrees of involvement or separation and the poles are called Closeness (becoming close to others) and Distance (moving further away from others), respectively. The vertical one is concerned with whether the person relates from an upper position (a position of dominance) downwards or from a lower position (of submission) upwards and the poles are called Upperness and Lowerness, respectively. It is quite possible to straddle both the vertical and the horizontal dimensions, which is the basis of the four intermediate positions of upper close, lower close, upper distant, and lower distant. Since relating covers the broad range of attitudes, postures, behaviours, and interactions which occur between people, the main objective of relating theory is the simplification, definition, classification, and quantification of the processes that are involved in the relating process, by breaking them down into the four spatial components and the four intermediate positions noted above. Together, these components are referred to as the eight ‘states of relatedness’, which are represented by the spatial structure that is called the Interpersonal Octagon (Birtchnell 1994).

Whilst animals can and sometimes do relate to each other (Shapiro 2010), it can be argued that humans relate to an even greater extent and in more complex ways. Animals sometimes relate to humans and sometimes humans relate to animals. Certain people relate in certain ways under certain circumstances. Lovers, friends, neighbours, members of the same family, and colleagues at work are inclined to be close. People who enjoy their own company or work in isolation are inclined to be distant. Leaders, managers, organisers, helpers, doctors, nurses, teachers, and parents are inclined to be upper. Children, pupils, patients, employees, and people seeking advice or help are inclined to be lower. Ideally people should be capable of relating in the appropriate manner according to the task that is in hand. There can also be times when a person can feel close, distant, upper, or lower in relation to the same person. Furthermore, a person may not like certain aspects of a particular person that he/she may otherwise feel close to. Relating does not necessarily take place in the here and now; we have internal images of people to whom we can or do relate. Internally a person can be aware of having a particular relationship with a certain other person or with certain other people. Humans also relate to God. Longing to meet with someone or dreading meeting someone are features of relating. We can even relate to the people who feature in our dreams.

A person who is capable of being either close or distant, or upper or lower, as and when it seems appropriate to be so, is referred to as being versatile; though being versatile does not necessarily mean consistently relating positively since all forms of relating are necessary for one to function as a confident and competent human being. Relating Theory is also concerned with the distinction that should be drawn between the directive, active form of relating (i.e. relating to another person), and the receptive, passive form of relating (i.e. being related to by another person – see ‘Being related to’ and ‘Interrelating’ below). All of this applies to each one of the eight relating positions of the Interpersonal Octagon in either positive or negative forms (see next section).

Positive and Negative Relating

An important feature of Relating Theory is that there are desirable and undesirable forms of each of the eight positions of the octagon. Thus, the theory distinguishes between the more pleasurable, friendly, constructive, and advantageous features of each form of relating – which are called positive – and the more unfriendly, less than pleasurable, more disadvantageous, and more destructive forms, which are called negative (i.e. selfish, clumsy, and offensive relating). The difference between positive and negative versions of each form of relating are a central feature of this book since most relating theorists do not pay sufficient attention to defining the difference between positive relating and negative relating. Positive relating is that which does not harm, disturb, or upset the person being related to. The positive relater pays attention to the possible effect that his/her relating might be having upon the person being related to and may modify what he/she says or how he/she says it in order not to be offensive. There are of course disturbing things that one person may have to say to another, such as ‘You have a serious illness’, although there are sensitive and insensitive ways of saying such things. An important aspect of Relating Theory, however, is that all states of relatedness are advantageous ways of relating under certain circumstances. For instance, seemingly ‘negative’ distant relating offers the relater the opportunity to be distant from others and appreciate privacy, whereas seemingly ‘negative’ lower relating offers the relater the opportunity to be guided, advised, protected, and cared for (see next section).

Classes of Positive and Negative Relating

Positive closeness is pleasurable involvement with another person, such that both partners experience it as something they both want and enjoy. Negative closeness is the anxious clinging of one person to another for fear that the relationship will break up, or the imposing of closeness upon another person who does not particularly want it. Positive distance is enjoying one’s own company and negative distance is feeling ignored or rejected by others. Positive upperness is leading, teaching, helping, or caring for another person and negative upperness is dominating, suppressing, threatening, or imposing one’s will upon another person. There are also positive and negative versions of the four intermediate positions of upper close, lower close, upper distant, and lower distant, which have been described in detail elsewhere (Birtchnell

1993/1996). Therefore, there is a positive octagon that is made up of all of the positive positions of each octant and a negative octagon that is made up of all the negative positions of each octant (see Fig.

1.1). The positive forms are all secure and constructive and the negative forms are all insecure and destructive.

Negative relating refers to relating incompetence. Since people need to relate in order to attain desirable states of relatedness, even if they cannot relate competently to attain them they will relate incompetently to do so. The three main forms of negative relating are cal...