eBook - ePub

Higher Education in the American West

Regional History and State Contexts

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Higher Education in the American West

Regional History and State Contexts

About this book

Higher Education in the American West: Regional History and State Contexts is the first comprehensive regional history of American higher education. It offers new historical research on how societal forces and state actions brought about the region'sone thousand two hundredinstitutions of higher learning in 15 western states.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Higher Education in the American West by Richard W. Jonsen,Patty Limerick,David A. Longanecker, L. Goodchild in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education Administration. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

REGIONAL, HISTORICAL, AND COMPARATIVE VIEWS

1

WESTERN COLLEGE EXPANSION: CHURCHES AND EVANGELIZATION, STATES AND BOOSTERISM, 1818–1945

Lester F. Goodchild and David M. Wrobel

A simple question frames this book: How did American higher education begin and develop in the West? Initially, the geographical expansion of the American West led frontier settlers to create towns and schools and even more. Town boosters then sought to lure other prospective settlers to their territories, states, and counties. Their hopeful and optimistic words reflected both their sense of promise and their anxiety about the future of their hometowns and regions.1 Seeking to educate their own children as well as Native American, Chinese, African American, and Mexican peoples in higher studies, these pioneers sometimes built academies, colleges, and nascent universities to attract others along the western trails. Unfortunately, these migrations and developments came at the expense of indigenous peoples, as the pioneers gradually moved indigenous tribes off their historic lands.

This chapter begins with an introduction and a discussion of the meaning of the West—beyond the more well-known idea of the frontier—offering an explanation of those historic educational realities from a more recent interpretive perspective on boosterism and evangelization. The second and third sections focus on the nature of boosterism whether to advance economic gains in building up the town or from religious groups to advance evangelization goals of Christianity. The fourth large section explores three major immigration movements in the 125-year development of western higher education from 1818 to 1945: (1) its developing era, 1818–1860; (2) its expansion era, 1861–1900; and (3) its service era, 1900–1945. Moving the discussion to a more contemporary focus in the fifth and sixth sections of the chapter, some comparisons of higher education with other parts of the country are broached with notes on the perils and promises in the region. A concluding coda overviews this expansionary era, describing how these beginnings led to more modern institutions of higher learning in the West, which is described more fully in succeeding chapters. This chapter lays the foundation for the first regional history of western higher education in the United States, and offers a developmental context for the demographic portrayal and public policy analyses of this region in the companion volume, Lester F. Goodchild, Richard W. Jonsen, Patty Limerick, and David A. Longanecker’s Public Policy Challenges Facing Higher Education in the American West (2014).

Moreover, in exploring how western colleges and universities were established since so little is known about their western development, this study draws on historical geographer D. W. Meinig’s ground-breaking four-volume study The Shaping of America (1986, 1992, 1995, 2006) and examines the flow of western migration and settlement patters of various groups.

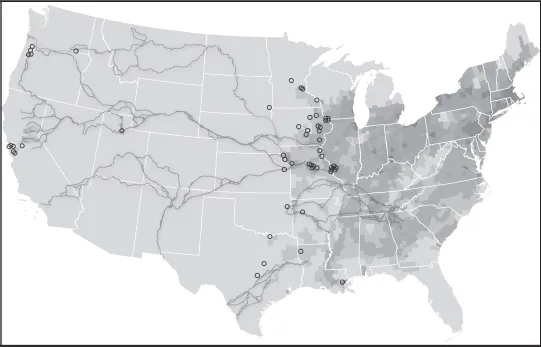

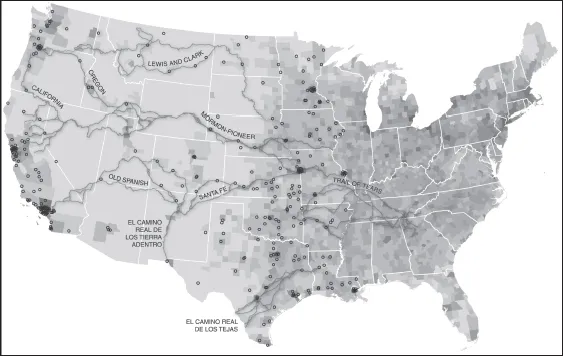

These major migrations led to the founding of colleges, following three major geographic patterns. First, western migration accounted for the development of St. Louis, the so-called Queen City to the West. Initial schools began there as early as 1818 and provided the first educational opportunities for the new groups heading west. Missouri would be the “Gateway to the West” for three major trails (namely, the Lewis and Clark, the Oregon, California, and Mormon, as well as the Santa Fe and Old Spanish). In addition, two important shorter trails (Trail of Tears and El Camino Real de Los Tierra Adentro) advanced institutional foundings to educate new peoples there. Perhaps just as critically, the region’s major rivers, such as the Mississippi, Missouri, and Columbia, provided waterways to create towns, schools, and colleges. Along these trails (shown in figures 1.1, 1.2, and 1.3), newcomers founded colleges in their towns, thus spreading higher education across the continent (Peters, 1996). Various motivations led to these developments. Among these early groups were Catholic and Protestant missionaries who sought to Christianize the native Pawnee, Shawnee, and Kansa Indian tribes, as well as some Cherokees forcibly moved from the East (Meinig, 1993, pp. 78–103; Hine and Faragher, 2000, 174–179). The initial success of these evangelization efforts led to the founding of schools (Malone and Etulain, 1989, p. 206). Although these schools were accessible to Indians, more often than not they were used for the new emigrants from the East (Elliott et al., 1976a, b; Patton, 1940, pp. 29–49, 141–191). Often neglected in historical educational research are the strong church calls for missionary work among the Indian tribes and how easterners encouraged extensive organizing and funding of these religious groups to go to the Middle West and eventually the Far West (Findlay, 2000, pp. 115–116).

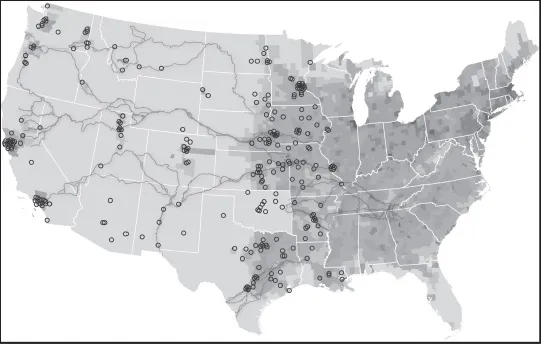

Subsequently, as western populations grew (as shown by the increasing density reflected in the US Census data from 1860, 1900, and 1940 and displayed in figures 1.1, 1.2, and 1.3), they soon followed the practice of developing state templates to augment their early town building along these trails or rivers: a college, a prison, and in some locations a state capital. Such civic boosterism occurred simultaneously or shortly thereafter with these earlier movements of religious and ethnic pioneer groups to a particular place, creating public colleges (Boorstin, 1965; Potts, 1977). Robert L. Church and Michael W. Sedlak in “The Antebellum College and Academy” in Education in the United States: An Interpretive History (1976, p. 140), described the process well:

Colleges were often founded right on the frontier line—not a generation after the founding of a town or of a state, but at the same moment as the founding of the town or state. Thus in states like Kentucky, Kansas, and Minnesota, colleges were founded before the population of the state rose above the 100,000 mark—if the 18 in 10,000 figure for college trained people can be said to apply uniformly across the country, each of these states established colleges before there were 200 college-trained residents in the state.

Similarly, western migration and town boosterism along these five trails or rivers accounted for most of the initial college building in the West.

Second, a much smaller southern migration brought schools to Arkansas and Louisiana in 1834, as new settlers crossed the Mississippi River or traveled up from New Orleans, and resolved their disputes with the native Osage, Creeks, and Choctaws, as well as some of the Cherokees immigrating from the East (Meinig, 1993, pp. 78–103). The Methodists established the Centenary College of Louisiana in Shreveport in 1825, while the Presbyterians founded the University of the Ozarks in 1834. Texas and Oklahoma would later benefit from this population surge toward the West.

An interior, eastern third migration occurred from coastal Washington, Oregon, and California. Clipper ships and steam ships brought passengers to the West who sought to discover gold, buy land, and create towns in the northwestern or in the old Spanish territories, as they moved toward the Rocky Mountains (illustrated by increasing population density, according to the US Census data, figures 1.1, 1.2, and 1.3). Their efforts led to both the Jesuit founding of Santa Clara College and the Methodist founding of the University of the Pacific in 1851, as the first institutions of higher learning in California (Elliott et al., 1976b; Giacomini and McKevitt, 2000; McKevitt, 1979) and later public colleges and universities.

These three migrations were the major forces for founding colleges in the West, before the transcontinental railroads in the 1870s changed western settlement patterns and increased population movements and densities (Milner, O’Conner, and Sandweiss, 1994, pp. 213–224; Nugent, 1999, pp. 77–80). In this fashion, and not surprisingly, Euro-American westward expansion (along with interior movement from the West Coast) forged a distinctive pattern of college development (Goodchild, 1999, 2002; Powell, 2007, Chapter 5, especially pp. 190–191). Churches, ethnic groups, and states celebrated their emerging towns with a hearty religious or civic boosterism that founded colleges. For example, St. Louis University, founded by the Catholic community of that town, began higher education in 1818, followed by a state mandate leading to the creation of the public University of Missouri in 1839. Similarly, the Methodist community having come across the Oregon Trail founded Willamette College in 1842, while Oregon State University opened in 1868. Demands for coeducation also found a home in the West, as the University of Iowa opened its doors to women in 1855 (Solomon, 1985). Many other western public institutions followed its lead. The 22 western states and territories in the continental United States thus comprise an interesting pattern of religious and civic college building development in the initial “boom” phase of western higher education during this national period (Thelin, 2004, pp. 41–42) (see the appendix for a list of the first religious and state college foundings in the 22 western states and those of Alaska and Hawaii). For our purposes, it is critical to discuss the meaning of the West at this juncture.

Figure 1.1 United States, Higher Education Developing Era, 1818–1860.

Figure 1.2 United States, Higher Education Expansion Era, 1861–1900.

Figure 1.3 United States, Higher Education Service Era, 1901–1940.

Sources: All three maps by Archie Tse.

Data on institutions for the three maps from Lester F. Goodchild,University of Massachusetts Boston. Wagon trails data from the Bureau of Land Management and the National Parks Service. Population density from Andrew Beveridge, Queens College/Social Explorer (U.S. Census data from 1860, 1900, and 1940).

THE IDEA OF THE WEST

How did the West come to hold such importance for these educational pioneers? The place is understood to be the land located west of the Mississippi River, which now comprises some 22 states. Beginning with the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, the new western lands were eventually bounded by “the forty-ninth parallel to the north, the Mexican border to the south, the Mississippi to the east, and the Pacific to the west” (Dippie, 1991, p. 115). However, the remaining chapters of this book focus on a different idea of the West—what we have designated here as the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education (WICHE) West. WICHE, now a 15-state compact, was created in 1951 to assist state higher education leaders and institutions through consulting, mutual policies and programs, and other activities (Abbott, 2004). Its member states are: Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oregon, South Dakota, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming. The WICHE West is thus different from the historic West.

For our purposes in this chapter, the meaning of the historic West can be better understood by using The Oxford History of the American West’s (Milner, O’Connor, and Sandweiss, 1994, p. 2) definition of the West as the “trans-Mississippi West,” bounded by the Mississippi River to the east and the Pacific Ocean to the west. Yet the meaning of this place has always resisted easy definition. Frederick Jackson Turner’s 1893 essay, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History” (reprinted in 1962), presented the West as a transitory frontier process through which Euro-American settlers brought their ideas of American civilization westward. They aggressively pursued the avowed right of manifest destiny in claiming all lands to the Pacific Ocean.

Yet, in their path stood other peoples: indigenous plains and mountain tribes, Spanish settlers and their government, and later the new republic of Mexico. Historical research in the past 30 years has shifted away from the triumphalist model of white westward expansion and toward a more critical framing of the western past. A critical figure in this transition, Patricia Nelson Limerick, in her 1987 book, The Legacy of Conquest: The Unbroken Past of the American West, emphasized the conquest of peoples of color and subjugation of the land. Deemphasizing the ethnocentricism and hyper-nationalism of Turner’s frontier thesis (p. 21), Limerick argued that the West was better understood as a process of conquest, that was much in keeping with the practices of other empires (e.g., Great Britain) in other parts of the world. More specifically, Limerick reenvisioned “the history of the West [as] a study of a place undergoing conquest and never fully escaping its consequences” (p. 26). Exploring the continuity between the West in the nineteenth century and the region in the twentieth, she paid special attention to core tensions that illuminate both the western past and present, noting that:

the contest for property and profit has been accompanied by a contest for cultural dominance. Conquest also involved a struggle over languages, cultures, and religions; the pursuit of legitimacy in property overlapped with the pursuit of legitimacy in way of life and point of view. (p. 27)

Soon after the publication of The Legacy of Conquest, Limerick took the lead in launching the New Western History movement with the mission “to widen the range and increase the vitality of the search for meaning in the western past” (Limerick, 1991b, p. 88). In this project of creating a regional history, the New Western Historians viewed: “first, the contesting groups; second, their perceptions of the land and their ambitions for it; third, the structures of the power that shape the contest” (White, 1991, p. 37; also see Limerick, 1991a, p. 77). Furthermore, responding to the power of a deeply embedded set of national stereotypes centered on the notion of a thoroughly positive frontier heritage as the wellspring of American exceptionalism, Limerick insisted that “in western American history, heroism and villainy, virtue and vice, nobility and shoddiness appear in roughly the same proportions as they appear in any other subject of human history.” She added that this observation would only be “disillusioning to those who have come to depend on illusions” (Limerick, 1991a, p. 77). Others took up her project as can be seen in Robert V. Hine and John Mack Faragher’s The American West: A New Interpretive History (2000), where the legacy of conquest stands clearly at center stage as groups contested for western lands.

This chapter explores the legacies of this western conquest. Indeed, the history of western higher education reflects how the results of this conquest led to Euro-American conquerors creating their own “western” culture in these lands. Town building led to school building that eventually led to the creation of colleges, schools of advanced learning. These initial log colleges were religious and civic backwaters, sometimes involving both conquerors and those conquered, although they were generally reserved for what would become the new majority in these western lands.

Building on Meinig’s model and Limerick’s definition then, we suggest that the meaning of the West be understood as the legacy of conquest, explora...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Part I Regional, Historical, and Comparative Views

- Part II State Development Perspectives and Federal Influences, 1945–2013

- Part III A Concluding Commentary

- List of Contributors

- Index