![]()

1

Introduction: Rediscovering First World War Theatre

Andrew Maunder

Throughout the dreadful years of the War, I continued my theatrical activities incessantly.

(Albert de Courville1)

The rise, fall and resurgence of interest in the theatre of the First World War represents many of the changes in approaches to the conflict that have taken place over the last one hundred years, and which the centenary commemorations beginning in 2014 have thrown into sharp relief. In the immediate aftermath of the war, the theatre industry was heralded as an integral part of the war effort, an example of the way Britain and her empire had pulled together. Through its various activities, the theatre was seen to have reached new heights of social responsibility. King George V praised ‘the handsome way in which a popular entertainment industry has helped the war with great sums of money, untiring service, and many sad sacrifices’.2 Yet in the years that followed, attacks on work that came to be seen as jingoistic and self-serving rapidly displaced war-time theatre as a something worthy of admiration, and its entertainments were re-cast as shallow and meaningless, ‘childish antics’ as George Bernard Shaw labelled them in 1919.3

The publication, in the 1920s and 1930s, of a series of memoirs by prominent elderly actors and music-hall entertainers, some of whom had been given official honours, helped intensify an emerging picture of a self-satisfied body of people who, despite the upheavals and devastations of war, had continued to rule over the realm of British theatreland as majestically as King George did his own dominions. With a careful elaboration of their war service, which in some cases seemed mostly to involve touring creaky old productions up and down the country or making high-minded recruitment speeches about glory from the front of the stage, it became easy to see the theatrical profession – or at least its most distinguished representatives – as too out of date and too pompous to speak meaningfully to a modern sensibility. In one (in)famous example, the celebrated male-impersonator, Vesta Tilley, now transmogrified into Lady de Frece, boasted of having recruited 300 men at a single performance in 1916, many of whom, readers could only assume, were later killed.4 In 1933 Gilbert Wakefield referred to the ‘bombast’ inherent in the reflections of this older generation of skilful self-advancers.5 Later, in 1941, James Hilton in his best-selling novel, Random Harvest, recalled another kind of entertainment. The novel’s hero, Smith, a traumatized First World War soldier, is shown going to the theatre:

[H]e sat in the third row at the first house of the Selchester Hippodrome that night and looked upon a show called Salute the Flag, described on the programme as ‘a stirring heart-gripping drama, pulsating with patriotism and lit by flashes of sparkling comedy’ [. . .] In the final scene in the last act [. . .] the heroine, a nurse, unfolded a huge and rather dirty flag in front of her, and with the words ‘You kennot fahr on helpless womankind’ defied the villain, who wore the uniform of a German army officer [. . .] until such time as the rest of the company rushed on to the stage to hustle him off under arrest and to bring down the curtain with the singing of a patriotic chorus. [. . .] This was designed to bring a round of applause.6

Although one wonders how exaggerated Hilton’s descriptions are, his intentions seem clear enough. He sought to make war-time theatre look grubby and grotesque, and did so by making fun of its transgression of two boundaries: good taste and veracity. Hilton thus singles out the unnatural accent of the actress playing the nurse which, when amalgamated with the play’s dialogue, points to one of the main criticisms made of war-time theatre, namely its failure to tell it like it was – its unreality. By emphasizing the company’s old-fashioned acting, Hilton, like Gilbert Wakefield, encourages an idea of war-time theatre as something stuck in an earlier age, its productions dictated by vulgar showmanship and newspaper stories about German villainy. As a collection of people far from the Front none of these performers, nor the playwright whose silly spy drama they are staging, have any interest in the real horrors of war which Smith and his comrades have encountered.

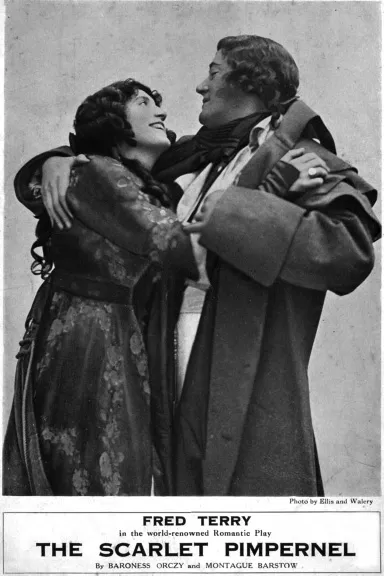

In contrast, and while renowned for his own fastidiousness, another soldier, Wilfred Owen, was able to appreciate war-time theatre’s activities without dwelling on its failures. Owen’s war-time letters show him eagerly attending West End productions of several middlebrow plays including, in 1915, Fred Terry’s production of The Scarlet Pimpernel (Figure 1.1) and Horace Annesley Vachell’s ‘excellent’ comedy Quinneys (1914–15) – but he also saw Shakespeare, including John Martin Harvey being romantic and hysterical in Hamlet (His Majesty’s, 1916) and Frank Benson’s touring company in The Merry Wives of Windsor (Garrison Theatre, Ripon, 1918). While at stationed at Ripon, Owen also saw two (unnamed) melodramas by Hall Caine. ‘How badly written they were!’ he commented. ‘I can’t stand Hall Cain [sic].’ Owen was more impressed by the work of two professional actors, John Leslie Isaacson and J. G. Pockett who, with their wives, organized amateur dramatics at Craiglockhart hospital in Glasgow, partly as recreation but also as therapy. During his own hospitalization for shell-shock, Owen, whose post-war dreams included becoming an actor, was chuffed to be cast in a small role in the trial scene from The Merchant of Venice, and later on in a bigger part in Wilson Barrett’s 1905 melodrama Lucky Durham. ‘I shall know what it really feels like to be on the stage’ he told his mother. It was at Craiglockhart, too, that in August 1917 Owen saw the Scottish singer-comedian Harry Lauder give a private performance for the inmates. Lauder’s son, John, had been killed at the Somme in December 1916 and Owen was touched by the gusto with which the grieving father carried on doing his patriotic songs, although he admitted not finding him especially funny. By this time Owen also had dramatic ambitions and wrote a play about the conflict, Two Thousand. Its aim, he declared, was ‘to expose war to the criticism of reason’, but he admitted taking a lead from the convoluted espionage dramas of the time, locating the play’s sensational second act in a secret bunker beneath the Atlantic. Owen’s last recorded theatre trip in June 1918 before being sent back to France for the final time before his death, was to the long-running London revue, The Bing Boys on Broadway. He felt he ought to go to see more Shakespeare but George Robey drew him in.7

Figure 1.1 Poster advertising Fred Terry in The Scarlet Pimpernel

It is interesting to speculate why the war-time theatre industry came to be so little regarded in the years that followed. In a very obvious sense, the decline and subsequent revival of interest is indicative of the kinds of shifts and changes in taste and understanding that Hans Robert Jauss details in his important Towards an Aesthetic of Reception (1982). Jauss would argue that the lack of interest can be attributed to a change in the ‘horizon of expectations’ and an ‘altered aesthetic norm’ that causes ‘the audience [to] experience formerly successful works as outmoded and [to] withdraw its appreciation’.8 Many of the plays of 1914–1919 were topical – and thus ephemeral. Some of the most successful – The Man Who Stayed at Home (1914), Seven Days Leave (1917), The Female Hun (1918) – had their origins in melodrama, a genre invariably given the label ‘bad drama’,9 whose characteristic excess would come to stand in opposition to realism and modernism – the dominant modes of aesthetic expression in the modern twentieth century.10 Moreover, in a country left reeling from the unprecedented slaughter, there was less inclination for theatrical flag-waving. By the late 1920s, a play like R. C. Sheriff’s Journey’s End (1928), while not pacifist in intention, seemed more ‘real’ and less irresponsible than the plays written during the war itself, particularly in the way it conveyed what the war had been ‘like’ for those who fought, the ‘lost generation’ of young men.11 Sneering at the war-time dramatists thus became something of a habit, a first step towards extolling the new and making oneself seem more sensitive. Among other observers there was resentment at what was perceived as war-time theatre’s tendency to shirk its cultural responsibilities but to profiteer nonetheless. George Bernard Shaw described the ‘higher drama’ as being ‘put out of action’ by silly entertainments expressly designed to exploit vulnerable soldiers on leave; ‘smiling men’ who because they ‘were no longer under fire’ were ready to be pleased by anything.12 Shaw’s reference to ‘higher things’ was partly directed at himself but he sounded a common theme. People remembered that before 1914 the London stage was a place of lively cultural cross fertilization and exchange, commercial and populist but also energized by imports from Ireland, France, Germany, the United States, and Norway among others.13 1911, for example, had seen the arrival of a new and potent influence: ‘Les Ballets Russes de Diaghilev’ and its charismatic star, Vaslav Nijinsky. In 1912, Harley Granville Barker’s stagings of The Winter’s Tale and Twelfth Night were also held up by some as having begun to modernize the British stage for the better. But there came to be a feeling that the war had stopped this. The radical ‘New Drama’, adventurously ‘speeding along in the van of progress’, as J. T. Grein, one of its champions put it, had shuddered to a halt.14 A sense of war-time audiences ‘disinclined for any [. . .] food for thought’,15 also helped build up this picture of artistic vacuity, encouraged by the popularity of the packaged exoticism of musicals such as Chu Chin Chow (1916; 2,238 performances) and The Maid of the Mountains (1917; 1,352 performances) not to mention the enthusiasm for revues: Shell Out! (1915; 315 performances), The Bing Boys are Here (1916; 378 performances), Zig Zag! (1917; 648 performances), Bubbly (1917; 429 performances).

For the succeeding generation of critics and theatre practitioners in the 1950s and 1...