- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Brands and businesses from across the globe have tried to leverage the India opportunity, based upon simplistic and widely-held assumptions. This book takes a critical look at these myths and contradictions from an inside perspective, presenting a fresh and nuanced perspective on the opportunities that the Indian market offers. It draws upon a wealth of data, from consumer research, market data, macroeconomic research, popular culture and case studies, to provide a thorough and compelling insight into what makes for success in the complex Indian market, based upon two decades of experience.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access India Reloaded by D. Sinha in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

chapter 1

The Trap of Mass-Market Thinking

Why Chasing a Billion is a Wrong Strategy

Why Did the Masses Not Buy the Nano?

In their growing-up days, today’s middle-class Indians fancied the Ambassador as the car of their dreams. An Ambassador was a round, voluptuous car with seats that resembled spring sofas of our living rooms. It was most often spotted in white with a beacon light atop – which signified that its owner was a high-powered government officer. The white Ambassador turned out to be a symbol of power, respect, and success. The car had a big presence on the Indian roads, both physically and symbolically. When a middle-class Indian said he wanted to own a car someday, he meant the Ambassador, because that was his idea of a car. Of course, there was an option in the square-shaped Premier Padmini, produced under license from Fiat. But the Ambassador dominated the Indian ideal of what a car should be.

On March 23, 2009, Ratan Tata, the Chairman of the Tata group launched the Nano – designed to fulfill every Indian’s needs and aspirations of owning a car. At the launch event, Mr. Tata spoke about the inspiration behind what he called the “people’s car.” He spoke of the need for an affordable transport for families riding on two-wheelers.

Today’s story started some years ago when I observed families riding on two wheelers, the father driving a scooter, his young kid standing in front of him, his wife sitting behind him holding a baby and I asked myself whether one could conceive of a safe, affordable, all weather form of transport for such a family. A vehicle that could be affordable and low cost enough to be within everyone’s reach, a people’s car, built to meet all safety standards, designed to meet or exceed emission norms and be low in pollution and high in fuel efficiency. This then was the dream we set ourselves to achieve [1].

Tata’s Nano failed to catch the fancy of the aspiring Indian middle-class that it was designed for. Nano’s sales declined dramatically after peaking to 74,527 in 2011–12. The numbers came down by more than 70% in two years to 21,129 in 2013–14. This was far below the annual production capacity of 250,000 Nanos at Tata’s plant in Sanand [2]. Later in August 2013, the brand attempted a makeover – targeting the urban youth with a jazzed up model and advertising which promised “awesomeness.” The people’s car had vacated its position and was trying hard to repackage itself as a smart city car for the urban youth.

Tata’s Nano failed its purpose because it did not live up to the ideal of a car that Indians have grown up with. The family on a two-wheeler that inspired Ratan Tata’s dream of the Nano was itself inspired by an Ambassador. Their idea of a car was a fulsome, voluptuous vehicle, well endowed with features, and that was above all a status enhancer. For this Indian family, the car was an answer to their social status first and their physical needs later. The two-wheeler was already meeting their physical mobility needs – it was economical and quick in cutting through the traffic. In retrospect, it’s easy to see that entry-level cars from Maruti Suzuki that succeeded the Ambassador – the Maruti 800 and Maruti Zen – were successful because they fulfilled the essential criteria of status and were well endowed with features.

Adding insult to the injury was the overt publicity of Nano as the cheapest car in the world. Imagine working hard through your life, riding a two-wheeler, and saving money in the hope that one day you would have enough to own a car. That day, the world around would look at you and recognize your success. If this is the dream you have nurtured, you don’t want to get caught driving a car that’s known to be the cheapest. As it turned out, the “cheapest car in the world” tag was antithetical to the great Indian emerging class dream.

The idea here is not to deride the strategy or the inspiration behind the Tata Nano. Nano is an important lesson for our way of thinking, we must learn from it. Nano isn’t a failure of product design or marketing strategy. Nano is a failure of how we think about mass markets – through the lens of affordability, not aspiration. The problem is with our vantage point – we look down on the lives of the aspiring class from our well-heeled and successful positions. From here, it appears logical that people who can’t afford a product should be happy to own a stripped-down version; that the rider of a two-wheeler would jump at the prospect of owning something that looks like a car if it’s affordable, even though it doesn’t fully match up to his specifications. Businesses are thinking stripped-down and downgrades when they are thinking of the mass consumer. The mass consumer on the other hand is seeking an upgrade. In the case of the Nano, the target consumer aspired to own a car that he had dreamt of, growing up around the Ambassador. He wanted to buy aspiration but we were selling him affordability.

Getting it Wrong

The idea of the mass-market consumer has been in vogue for over two decades now. In 1992, India opened the gates of its economy to the world. A few years later, in 1998, C. K. Prahlad discussed the idea of the fortune at the bottom of the pyramid. Almost overnight (considering the previous many decades of little action), India turned into a treasure-chest for global businesses. With a promise of 300 million middle-class consumers, almost the size of America, it was on the agenda of every business house and private equity fund. Mass markets in general and India specifically were becoming fashionable.

However, what looked like a treasure chest turned out to be a long-winded treasure hunt. International and Indian businesses took to the mass India opportunity like bees to honey, only to realize that it was indeed a complex honeycomb. Navigating and negotiating the mindset of the mass consumer hasn’t been an easy ride for anyone. It has been a long battle of nerves fought in rather hostile terrains. Most international businesses born in Europe or America are used to serving much smaller populations. Moreover, these populations have been through a different socio-economic trajectory than emerging markets such as India. It was assumed that the emerging market consumers would logically behave the same way as the developed market consumers, just that they were poorer. However, such assumptions have backfired.

Brands and businesses across categories such as automotive, telecom, retail, and aviation have been a part of this hysterical pursuit of the mass market in India. Unfortunately, many assumptions made in the pursuit of this market have gone wrong. The so-called “value-minded” Indian consumer has often reacted out of character, the much-touted demographic dividend hasn’t borne fruit, and, despite the success in grabbing large market shares, profitability has been elusive. The telecom business is a case in point – despite a staggering number of more than 900 million subscribers, almost all telecom companies remain debt-ridden and unprofitable. There are several reasons why the promise of the large and growing mass-market has turned out to be a wild goose chase.

The Opportunity that Wasn’t

To begin with, the size of the opportunity itself was over projected. Large numbers and predictions such as 300 million middle class, 500 million below the age of 25, and the fifth largest consumer economy by 2025, whipped up euphoria [3]. When reports bandied the 300 million number as the size of the middle-class in India, they didn’t mention that the definition of the middle-class wasn’t the same as that in the Western world.

While none of these numbers were untrue, they were projected out of their context, both demographic and cultural. Much was made of the large numbers of people without any interrogation of either their motivation or ability to buy the products and services that the world thought they should be buying. It’s interesting to evaluate these numbers, which formed the basis of several India-entry and expansion plans, in the context of some other available data.

The Census of India is the largest survey undertaken by the government of India and is possibly the most authentic demographic data available. In addition to the population count, it also captures basic living conditions. A look at the census data about ownership of houses and other consumer products gives a context to the predictions around the great India opportunity.

A lot has been documented about the stark contrasts in India’s growth story – the uninhabitable slums of India thriving amidst the steel and glass of high-rise buildings, the debt-laden farmers committing suicide while food inflation robs the urban dwellers of their meager income are all real images of a rapidly changing India. The Census of India helps us separate these two worlds that we see and read about in movies and books on India.

According to the Census of India 2011, nearly half of India, more than 600 million people, doesn’t have access to basic necessities [4]. The census identifies a total of 246 million households in India (accounting for 1,210.6 million people), of whom 167 million are rural and 78 million urban households. Now consider this, 49.8% of the households in India don’t have access to a latrine, they use open spaces; only 43.5% have access to tap water for drinking and nearly 45.5% live in houses with mud flooring. According to these statistics, India isn’t a market of a billion people. As almost half the population struggles for basic necessities, this leaves only the other half, around 600 million people, in the consumption bracket.

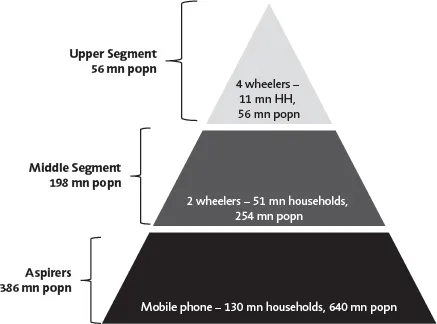

The image of a sadhu holding a mobile phone is often used in the context of emerging India. It represents the simultaneity of an India steeped in tradition and enticed by technology. A mobile phone in today’s India is no longer a good-to-have luxury; it’s a must-have necessity. It connects millions of daily wage earners such as plumbers, carpenters, and electricians to their livelihood. It keeps millions of migrants in touch with their families back home. It also doubles up as an entertainment device during tea breaks. According to the Census 2011, 53.2% or 130 million households owned mobile phones, which covers an estimated 640 million people. Mobile owning households are even greater in number than television owning households. Given that a mobile phone today is the basic unit of consumption, it can perhaps be used as a surrogate to define the size of the consuming population in todays’ India. Thus 640 million mobile phone users are as far as the boundaries of consumption extends in India (see Figure 1.1).

As we climb up the asset ownership ladder, 21% of the total Indian households or 51 million households own a motorized two-wheeler (scooter, motorcycle, or moped). This makes about 254 million people. The Census of India does not provide overlap data, so we don’t know how many people who own motorized two-wheelers do not own mobile phones or vice versa. But for the sake of simplicity let’s assume that those who own motorized two-wheelers also own mobile phones. The gap between two-wheeler owners and mobile phone owners is 386 million people. We could classify them as the aspiring class. They don’t yet belong to the middle but are trying hard to get there.

FIG 1.1 Class segmentation based on ownership of goods

Source: Census of India, 2011.

There are 11 million households or 56 million people who claim ownership of a four-wheeler (car, jeep, or van). Clearly the middle segment in India lies between the 254 million motorized two-wheeler owners and 56 million four-wheeler owners. This gives us 198 million people who form the middle segment. We must remember that this segment doesn’t even own four-wheelers, and may not confirm to the definitions of the middle class as understood in Western countries.

The 56 million four-wheeler owners are then the upper segment in India. Of these 7.6 million households, covering an estimated 37 million people, own a computer with Internet. It thus appears that the upper segment population in India accounts for somewhere around 37 to 56 million people and not more. This 56 million also includes the ultra-rich segment of India. Unfortunately, the Census of India doesn’t track ownership parameters beyond this level. This keeps us from estimating the size of the rich in India using census data. However, according to a study conducted by Kotak Bank and Crisil in 2012–13, the Ultra High Net Worth Households (ultra HNHs) were estimated at 100,900, which means 494,982 people. This population is predicted to triple in the next five years to 329,000 households in 2017–18 [5]. Broadly speaking, this is the size of the super-rich segment in India.

In a quick snapshot, we are talking about 640 million people with mobile phones, which is the total consuming class in India. Out of these, 386 million don’t even own a two-wheeler – they are the aspirers. Around 198 million own two-wheelers but not cars; we can call this the middle segment. 56 million are the upper segment, which owns four-wheelers; this includes around 500,000 super rich.

These estimates are at best that. They use basic consumption surrogates to define the marketable population. They also assume that the path to the ownership of these durables is linear, that is, someone who owns a two-wheeler is more affluent than someone who owns only a mobile, and so on. The estimates do not take into account income, education, or employment criteria. The census numbers may also suffer from under-declaration, as people are generally reluctant to declare the real picture of their wealth to avoid paying income tax.

Despite the limitations in the quality of data and the simplistic assumptions, these numbers give us a more realistic picture of India’s potential. These numbers put into doubt the estimate of a 300 million-strong middle class population, given that the number of people who own at least a four-wheeler stands at just 56 million. Even the number of two-wheeler owners is less, at 254 million, than the much touted 300 million middle class population. This analysis brings to the fore the overestimation that has misled most of India’s entry and expansion strategy for the last two decades. Buoyed by projections of a large middle class population and an even larger bottom of the pyramid, most brands and businesses in India set up for a volume driven strategy, chasing a market of a billion people.

The Cost of Reaching Out

Scale became a pre-requisite for reaching out to the millions of Indian consumers. Depending on the nature of the industry, this required disproportionate investments. In manufacturing, it meant investing in large scale production capacities; in aviation it meant a larger fleet of aircrafts; in retailing it meant opening up stores as far as tier 2 and tier 3 towns and in telecom it meant extending the reach of the network to cover 900 million plus subscribers. Mass-market thinking meant that distribution had to be put ahead of differentiation.

The commercial interest in India was growing faster than the government’s intention and ability to extend infrastructure. In many cases, businesses had to work their way around the non-availability of infrastructure support. Coca Cola innovated around a lack of electricity in rural India by providing smaller sized and customized solar powered refrigerators – eKOcool. Telecom service providers and banks had to put up towers and ATMs in far-flung areas. That businesses in emerging markets needed to innovate and build their own infrastructure became a subject of celebration in case studies, books, and conferences. At the same time, the costs of doing so were prohibitive and were piling up for many businesses.

Air Deccan was India’s first low cost airline, which sold tickets starting at Rs. 500 ($10). Captain Gopinath launched the airline with a vision of helping the common man to fly. The logo of Air Deccan was the common man – borrowed from a political cartoon series in the Times of India, the country’s prominent daily. Air Deccan aspired to bring flying to the masses; it brought air tickets close to train tickets in price. Its advertising showed an emotional story of a father who flies in a plane for the first time to meet his son. The back-story in the ad shows how the son was obsessed with planes when he was a child. His father had built him a toy plane, chiseling it out of wood. This time around, the son has sent air tickets for the father who works and lives in the village. The father is shown carrying his son’s favorite toy plane in his handbag. The ad signed off: for millions of Indians, flying will no longer be a dream. It’s true that flying is still a dream for millions of Indians and this ad did put a lump in people’s throats. Despite its noble intentions, Air Deccan ran out of ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 The Trap of Mass-Market Thinking: Why Chasing a Billion is a Wrong Strategy

- 2 The Poor Want Purpose: Why Marketing Needs to Be Social in India

- 3 Safe Choices: Why Do Indians Like Standing in the Longest Queues?

- 4 Many Indias Make One India: How India’s Unity is More Useful than its Diversity

- 5 Success Overdrive: Has the Success Narrative Been Overcooked?

- 6 Breaking Stereotypes: Why Youth Marketing Needs to Go beyond Risqué Content

- 7 Sexy Everything: Seeking Titillation in Design, Tastes, and Experiences

- 8 Spruce Up the Service: Why Jugaad is an Enemy of Good Service

- 9 New Pockets of Opportunity: Looking Beyond the Mainstream

- 10 Powered by People, Not Policy: What Makes India’s Growth Story Sustainable?

- References

- Index