- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Drawing on historical and contemporary evidence, this book argues that growing environmental degradation and wealth inequality are linked to how nature is exploited to create economic wealth. Ending the under-pricing of natural capital and insufficient human capital accumulation is essential to overcoming structural imbalance in modern economies.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Nature and Wealth by Edward Barbier in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Financial Services. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Origins of Economic Wealth

Introduction

The purpose of the following chapter is to trace the historical origins of our present-day concept of wealth, by examining how human perceptions of wealth have evolved over previous eras. These changing perceptions are important to understanding our present predicament – which is to “undervalue” the contribution of nature to our economies. This misalignment between our exploitation of nature and the creation of wealth is fundamental to the structural imbalance in modern economies. In subsequent chapters, we explore the causes and consequences of this imbalance.

If you asked anyone today “what is wealth?” chances are you would get similar answers: precious jewels, bank accounts, mansions, estates, stocks and bonds, personal art collections, private yachts and jets. These material possessions and financial assets are what we recognize in modern society to be the “trappings of wealth”.

Yet, for most of our existence, humans would have been puzzled by this modern view of “riches”. They would even have had trouble in defining a term like wealth. The reason is that it is actually a fairly new social concept; what we consider to be wealth today has evolved through many millennia of human social and economic development.

For hundreds of thousands of years, humans lived as hunter-gatherers and had little interest in accumulating material possessions or land and natural resources. In these societies, mobility and adaptability to nature were the key social traits that guaranteed communal economic survival. Wealth was a meaningless concept for early humans.

Once hunter-gatherers were supplanted by farmers and herders, around 10,000 years ago, wealth creation began in earnest. For thousands of years, with agriculture as the dominant economic activity, humans associated affluence with the accumulation of fertile land and possession of abundant natural resources, such as wood, water, building stone, precious stones and gems, and metals. Labor was important, but less so than livestock for food, transport, work and even warfare. In other words, basic natural resource assets – or natural capital – were the main sources of economic wealth for both individuals and human societies.

For the past couple of hundred years, and especially since the Industrial Revolution in the mid-18th century, we have come to view wealth a little differently. Today, the close association between natural resources (including land) and wealth accumulation no longer exists. In modern societies, wealth is often referred to as “capital”, which is defined as the sum total of non-human assets that can be owned and exchanged on some market.1

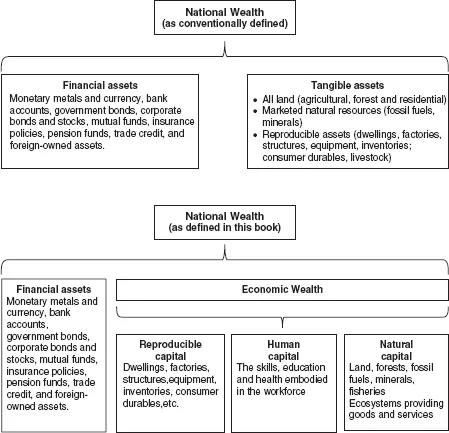

As depicted in the top part of Figure 1.1, a distinction is usually made between two types of capital. The first is tangible assets, which support the production of goods and services in an economy. The second form of capital is financial assets, which represent various stores of wealth as well as claims on others in the economy. Together, financial and tangible assets comprise the national wealth or national capital of an economy, which is the total market value of everything owned by the residents and government of a given country at a given point in time.2

Figure 1.1 National wealth and economic wealth

Because they can contribute to current or future production, the tangible assets of an economy are conventionally defined as all land (e.g., agricultural, forest and residential) and reproducible capital (e.g., dwellings and real estate; factories, structures, equipment, etc.; inventories; consumer durables; and livestock).3 However, some economists also include as tangible assets those natural resources of an economy, such as oil, natural gas, coal and other minerals that can also be owned and exchanged on markets.4 In contrast, financial assets include monetary metals and currency, bank accounts, mutual funds, bonds, stocks, insurance policies, pension funds, mortgages, government bonds, corporate bonds and stocks, trade credit and foreign-owned assets.

In principle, there is an important connection between financial and tangible assets, namely that many investments in land, dwellings and reproducible capital are funded by an enterprise or an individual borrowing, or incurring debt, in order to pay for such investments. Such new debt or borrowing is referred to as acquiring financial liabilities. But incurring additional financial liabilities in an economy can only happen if another individual or enterprise is willing to finance this debt, which becomes the latter’s financial asset. Thus, the acquisition of new financial assets by all domestic sectors of an economy should be balanced by the sum total of new financial liabilities.5

Although the accumulation of financial and tangible assets is important, they may not represent all the capital that is fundamental to the successful working of an economy, both now and into the future. Instead, if we are interested in the economic wealth of a nation, we are interested in all forms of capital that can contribute to the current and future well-being of all those who depend on the economy for their livelihoods.

In this book, we make the case that the conventional definition of tangible assets is incomplete, because it leaves out several important assets that are essential to current and future economic livelihoods. Instead, as indicated in Figure 1.1, we consider the national wealth of an economy to include financial assets and economic wealth. The latter comprises three distinct assets: manufactured, or reproducible, capital (e.g., roads, buildings, machinery, factories, etc.), which we noted above is also an important tangible asset; human capital, which are the skills, education and health embodied in the workforce; and natural capital, including land, forests, fossil fuels, minerals, fisheries and all other natural resources, regardless of whether or not they are exchanged on markets or owned (see Figure 1.1).6 In addition, natural capital also consists of those ecosystems that through their natural functioning and habitats provide important goods and services to the economy, or ecological capital.7

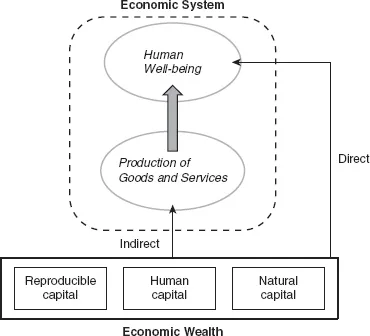

These three forms of capital – reproducible, human and natural – should be considered the real wealth of an economy, because they can either benefit the well-being of humans directly (e.g., a person is better off if she is healthy; people enjoy a cleaner environment and well-functioning ecosystems, etc.), or they benefit humans indirectly through contributing to current or future production (e.g., more machines, raw material and energy inputs, and better skilled workers can increase the output of goods and services that people consume). Because the accumulation and maintenance of reproducible, human and natural capital contribute either directly or indirectly to increasing human well-being, both currently as well in the future, these three forms of capital comprise economic wealth. Figure 1.2 illustrates this fundamental relationship diagrammatically.

Reproducible, human and natural capital either directly support current and future well-being or do so indirectly through contributing to current and future production of goods and services in an economy. Thus, these three assets comprise the economic wealth of a country.

To summarize, in this book we define national wealth to consist of financial assets and economic wealth. The focus of this book is mainly on the three assets that comprise economic wealth – reproducible, human and natural capital – that support the production of goods and services in an economy. As we shall see, how economies today accumulate and use these three types of capital affects current and future well-being, as well as the composition of our overall national wealth. For example, while we are busy accumulating financial assets and reproducible capital, depreciation of our natural and ecological capital is proceeding at an alarming rate. We may also be under-investing in human capital. This pattern of wealth accumulation and composition has led to structural imbalances in modern economies that threaten their sustainability.

Figure 1.2 Economic wealth and human well-being

The creation of wealth

The accumulation of wealth is, in fact, a relatively new social phenomenon. Homo sapiens emerged 200,000 to 250,000 years ago, and for around 90% of our existence, we survived by hunting wildlife and gathering wild plants and foods. Early human societies that engaged in such activities had little interest in amassing wealth. Hunter-gatherers had few material possessions, and they were shared or divided equally. Accumulation was simply not a priority for this way of life, for three principal reasons.8

First, hunters had to follow their prey and foragers had to gather new sources of wild resources. They lived in small bands and groups, so that they could move quickly across wide stretches of territory. Such highly mobile and small hunter-gatherer societies could not carry around much in the way of material possessions – other than what was essential for catching, collecting or containing food.

Second, mobile and small hunter-gatherer societies were never in one place long enough to own much land or other natural resources. If they did claim territory, land and resources, it was generally through communal ownership and equal use. If one group or individual tried to control the richest land or resources, the others could simply “vote with their feet” and move elsewhere. Humans were scarce, so finding new hunting and foraging grounds was relatively easy. In contrast, natural wealth was everywhere and plentiful, so there was no need to hoard, possess or protect it.

Finally, the tools, clothing and other essential items for survival were relatively easy to make. The knowledge and skills to make such objects were shared and taught, and the raw materials for manufacturing were readily available in the wild. Any special ceremonial or ritual objects were communal property.

The absence of wealth and inequality among hunter-gatherer societies changed with the development of agriculture as the dominant human economic activity. The long period of history that encompasses the demise of hunting-gathering and the rise of agriculture is often called the Agricultural Transition, because it took around 7,000 years to unfold and spread globally. This process may have started in 10,000 BC, with early experimentation in crop planting by sedentary hunter-gatherers in different parts of the world. By 5000 BC much of the global population lived by farming, and by 3000 BC the first agricultural-based “empire states” emerged.9

The Agricultural Transition fostered agricultural-based production systems that routinely created food and raw material surpluses, which in turn facilitated urbanization, manufacturing, trade, and of course, the creation and accumulation of wealth. The principle stores of value were land, livestock and material possessions. However, the difference in wealth and status among early farmers is also evident through lavish burials and other ritualistic practices, the type and distribution of ceremonial goods, the size and location of dwellings and storage facilities, and evidence of improving stature and health.10 And, as such distinctions in wealth and status grew within early farming societies, so did social inequality.

Around 3000 BC, agriculture had become sufficiently advanced that it was able to support complex, urban-based societies in some regions. These societies quickly evolved into the first “ancient civilizations” of Mesopotamia, Ancient Egypt and India, and also the Greek city-states and Roman Empires. From 1200 BC onwards, large cities and empires were also present in China and East Asia.

Although dependent on surrounding agricultural land for food surpluses, the urban centers that controlled these great empires and early civilizations also required a variety of natural resources to sustain their economic wealth and power, and to provide security in times of drought, plague, war and other calamities. Imperial expansion and urban growth required securing new supplies of fertile land, natural resources and raw materials. As described by the historian Herbert Kaufman, obtaining such sources of wealth was essential to the “polities” governing these empires:

Labor, arable land, water, wood, metals, and minerals (building stone, precious stones, and semi-precious stones) were the major resources of the polities ... although draft animals and horses for warfare were also important in some cases. Where these were in plentiful supply, economies prospered, sustaining government activities that assisted and facilitated productivity. The political systems that lasted long, or that displayed great recuperative powers, were usually well-endowed in many of these respects and were therefore able to acquire by trade or intimidation or conquest what nature did not bestow on them.11

Not surprisingly, it was these ancient land-based empires that first recognized wealth creation as the primary goal of an economy. Wealth and its accumulation were elevated to the highest social status. For example, ancient Greek religion and myths even had a god of wealth, Plutus, who was the subject of a popular Greek comedy written by Aristophanes in 388 BC.

For early agricultural societies and civilizations, the most valuable capital was fertile land, natural resources and raw materials. Precious gems and metals were also accumulated, both as status symbols a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- 1 The Origins of Economic Wealth

- 2 Natural Capital and Economic Development

- 3 Wealth, Structure and Functioning of Modern Economies

- 4 The Age of Ecological Scarcity

- 5 Structural Imbalance

- 6 The Underpricing of Nature

- 7 Wealth Inequality

- 8 Redressing the Structural Imbalance

- 9 Making the Transition

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Index