eBook - ePub

Inclusive Growth and Development in India

Challenges for Underdeveloped Regions and the Underclass

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Inclusive Growth and Development in India

Challenges for Underdeveloped Regions and the Underclass

About this book

India is one of the fastest growing countries in the world. However, high economic growth is accompanied by social stratification and widening economic disparity between states. This book illustrates some important aspects of underdevelopment and the process by which the underclass is left behind by focusing on the country's most neglected regions.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Inclusive Growth and Development in India by Y. Tsujita in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

How Agriculture in Bihar Lagged Behind: Implications for Future Development

Koichi Fujita

1.1 Introduction

The Bihar economy started to grow rapidly after the mid-2000s, drawing much attention from academics and policymakers of India. However, since the gap between Bihar and the other states of India was so large, the immediate impact of such a high growth remained rather insignificant, although if the high growth continues, say, for one or two decades, consequences will be substantial. In fact, the per capita net state domestic product (NSDP) at current prices in Bihar was Rs. 8341 in 2005–2006, only 30.8% of the Indian average and 58.6% of the second lowest state, Uttar Pradesh. And it remained at Rs. 20069 in 2010–2011, which was still only 36.6% of the Indian average and 77.0% of Uttar Pradesh (Ministry of Finance, Gov. of India, 2012).1

What was the engine of the spectacular growth in Bihar after the mid-2000s? The author conducted a growth-accounting analysis for the periods 1999–2000 and 2008–2009, and discovered that trade/hotels/restaurants contributed to 28.7% of growth (out of a total of 86.1%, not 100%, probably due to data inconsistencies), followed by construction (14.0%), agriculture (13.0%) and so on (Fujita, 2012). It was hypothesised that the progress in the construction sector (especially road construction) by public sector investment in Bihar stimulated in turn the growth in trade/hotels/restaurants and other related sectors like transport/storage/communication (5.4%).

The high contribution of agriculture was due not only to its large share in NSDP but also to the high growth rates achieved by the sector – the average annual growth rate of agriculture during 1999–2000 and 2008–09 was 3.02%. Such a high growth was quite encouraging, especially since the economy of Bihar is still agrarian and many people are still engaging in agriculture, either directly or indirectly.2

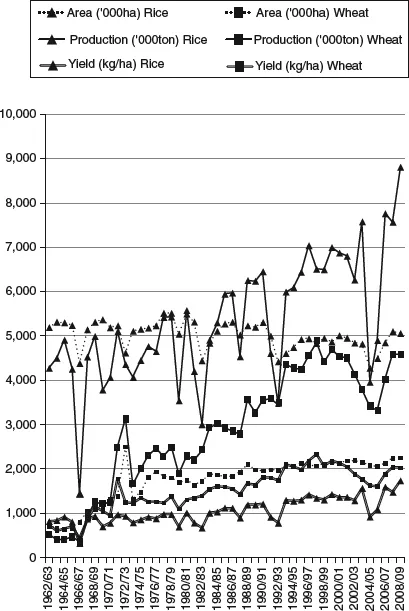

The rapid growth in agriculture can be attributed to a different mechanism of growth, other than public sector investment as in the construction sector mentioned above. It is noteworthy that rice production in the state has started to accelerate in recent years, with a rise in land productivity (see Figure 1.1). Agriculture in Bihar has been suffering from an extremely low crop yield for a long time. The backward agricultural sector is probably one of the main reasons behind the state’s economic backwardness and mass poverty.

What then has been happening in the agricultural sector in Bihar in recent years? Addressing this issue is quite critical and leads us to two specific and closely related questions. Why has crop yield, especially rice yield, in Bihar been stagnating for many years at an extremely low level? And what caused it to increase in recent years? The chapter aims to answer these questions.

It has been argued that Bihar’s agricultural backwardness is basically due to the problems in its agrarian structure: inequitable land distribution and the ‘semi-feudal mode of production relations’ between landlords and sharecroppers/agricultural labourers. However, this should not be taken for granted at all. In this chapter, we first re-examine why the agricultural sector has lagged behind through a careful investigation of crop production statistics. We then make a comparison with the case of West Bengal and Bangladesh. Next we present some critical findings from field surveys conducted in various parts of rural Bihar in 2011 and 2012. Finally, after analysing why rice yield has started to increase of late, we discuss the prospects for agricultural development in the state.

The chapter is divided thus: the Section 1.2 critically examines the dominant, prevailing hypothesis on the backwardness of Bihar agriculture. Section 1.3 scrutinises agricultural statistical data, especially for rice and wheat, so as to re-evaluate the development process of agriculture in Bihar since the 1960s onwards, in a comparative analysis with the experiences of West Bengal and Bangladesh. Section 1.4 explores the key issue why Bihar has been bypassed by the rice Green Revolutions, based on information and insights obtained from our field surveys in the last two years. Section 1.5 discusses the role of the land reform programmes in West Bengal’s accelerated agricultural growth after the 1980s. The direct effect of the land reforms on agricultural growth is negated, which supports our argument that technological factors, rather than problems in agrarian structure, have been the true barrier for the development of the rice sector in Bihar. In Section 1.6 we discuss the prospects for agricultural development in Bihar, leading to the conclusion in the Section 1.7.

1.2 Critical review of major arguments on the backwardness of agriculture in Bihar

Several major arguments have been put forth to explain the backwardness of agriculture in Bihar, and in eastern India in general, of which Bhaduri’s (1973) is the most well known. Bhaduri attributed the agricultural backwardness to the ‘semi-feudal mode of production relations’ in agriculture. His argument is summarised as follows. The agrarian structure in eastern India is characterised by the presence of a few big landlords and many sharecroppers. It is assumed that the sharecroppers are perpetually indebted to their landlords, who provide consumption and production loans and who earn income from both land rent and interest revenue from such loans. Under such a situation of ‘semi-feudalism’, even if new technologies in agriculture become available, landlords are not willing to adopt them because this would raise the income of sharecroppers, thereby reducing their dependency on consumption loans. Therefore, even if income from land rent were to increase through the adoption of new agricultural technologies, income from interest revenue would decrease and as a result, total mixed income of the landlords would dip.

Bhaduri’s argument immediately attracted much criticism, from both theoretical and empirical points of view. Newberry (1974) questioned it from a theoretical viewpoint, arguing that under the ‘semi-feudal mode of production relations’, landlords are able to extract all the benefits from the adoption of new agricultural technologies, such that the income of sharecroppers does not increase. Srinivasan (1979) also refuted the argument by calculating arithmetically that even if all the assumptions made by Bhaduri were true, the total mixed income of the landlords would still increase. Bardhan and Rudra (1978), on the other hand, went back to the basics and proved through their empirical research in a number of villages in eastern India that the major assumptions made by Bhaduri did not even exist in the concerned region.

Nonetheless, despite all the criticism, Bhaduri’s argument remained popular, right till today. The ‘semi-feudal mode of production relations’ in eastern India, which has existed in the region since the British colonial era, especially the introduction of the Zamindari system in 1793, has been blamed for the economic backwardness of the region. Bhaduri’s argument was also validated to some extent when agriculture in West Bengal started to grow rapidly after the 1980s, soon after the success of the radical land reform programmes implemented by the left-front government since 1977.

Bardhan (1984), on the other hand, asked why private tubewell irrigation, a key factor in the promotion of the Green Revolutions in north-western India, was not diffused in eastern India, and attributed this to the small and fragmented farm structure in the region. He argued that unlike Punjab, where a land consolidation programme was successfully implemented in the 1950s, eastern India was bypassed by the Green Revolutions because of the lack of private tubewell irrigation, which in turn was mainly caused by the small and fragmented farms, as the economies of scale in tubewell irrigation could not be realised in eastern India under such disadvantageous farm conditions.

In reality, contrary to Bardhan’s observations, a large-scale diffusion of tubewells had started in West Bengal and Bangladesh since the early 1980s, although the structure of small and fragmented farms remained unchanged. The rapid diffusion of private tubewells, especially shallow tubewells (STWs) induced a dramatic expansion of summer rice (boro) planting area. Coupled with the adoption of modern varieties (MVs),3 this led to a rapid increase in rice production. The key factor was the widespread development of a groundwater market among farmers, which made the rapid diffusion of private tubewells possible even under the small and fragmented farm structure (Fujita, 2010).4

This leads to next question: why did the rapid growth in the rice sector after the 1980s, sparked by the diffusion of private tubewells, bypass Bihar, unlike West Bengal and Bangladesh? Can we single out the ‘semi-feudal’ mode of production relations in agriculture, which has persisted in Bihar until today, as the fundamental barrier, especially considering the success of the land reform programmes in West Bengal? We argue instead that it is technological factors, not problems in agrarian structure, that were the main causes of the backwardness of Bihar agriculture, especially in the rice sector. Let us now proceed to a detailed examination in the next section.

1.3 Analysis of the rice and wheat sectors in Bihar since the 1960s

Figure 1.1 illustrates the performance of the rice and wheat sectors in Bihar since the early 1960s until the late 2000s. It should be noted that Bihar was separated into two states (Bihar and Jharkhand) in November 2000, but the figure reflects data for the old (greater) state of Bihar.

Figure 1.1 Performance of rice and wheat sector in Bihar (old state)

Source: Ministry of Agriculture (Gov. of India), Agricultural Statistics at a Glance, various issues.

At a glance, it can be seen that wheat, which was a very minor crop in Bihar until the mid-1960s, started to grow very fast thereafter, and by the mid-1990s, had become one of the two major cereal crops in the state, although its production began to stagnate after that. The area under wheat crop, which was only around 70,000ha in the early 1960s, increased dramatically and reached its peak in 1972–1973 at 250,900ha. The yield of wheat crop, which was only 0.6–0.7 ton/ha before the mid-1960s, also increased rapidly, exceeding 1.5 ton/ha by the mid-1980s and reached more than 2.0 ton/ha in the mid-1990s. Accordingly, wheat production increased from a mere 0.4–0.5 million ton in the mid-1960s to 3 million ton in the mid-1980s and nearly 5 million ton by the end of the 1990s.

In sharp contrast, rice production remained largely stagnant and even declined in terms of per capita production until the mid-1990s, against a backdrop of rapid population growth in the state. This sharp contr...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- List of Contributors

- List of Acronyms

- Introduction

- 1 How Agriculture in Bihar Lagged Behind: Implications for Future Development

- 2 An Analysis of Rural Household Electrification: The Case of Bihar

- 3 Caste, Land and Migration: Analysis of a Village Survey in an Underdeveloped State in India

- 4 Education and Labour Market Outcomes: A Study of Delhi Slum Dwellers

- 5 Poverty and Inequality under Democratic Competition

- 6 The Burden of Public Inaction: Agrarian Impasse in Growing Bihar

- 7 Transformation of Field Development Bureaucracy in Uttar Pradesh: Indigenisation and the Senses of Bureaucratic Discretion and Satisfaction

- Index