eBook - ePub

The Palgrave Handbook of Experiential Learning in International Business

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Palgrave Handbook of Experiential Learning in International Business

About this book

The Handbook of Experiential Learning In International Business is a one-stop source for international managers, business educators and trainers who seek to either select and use an existing experiential learning project, or develop new projects and exercises of this kind.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Palgrave Handbook of Experiential Learning in International Business by V. Taras, M. Gonzalez-Perez, V. Taras,M. Gonzalez-Perez in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Theories and Concepts of Experiential Learning in International Business/International Management

1

Introduction: Experiencing the World

Allan Bird

Introduction

All learning is experiential. Nothing that we know comes from any source other than our own experiences. Think about it. Think of something you know. How did you learn about it? Did you listen to a lecture? You experienced someone telling you about it. Did you learn it through a book? You experienced reading about it. Did you learn it by watching a movie or television programme? You experienced watching it. Did you build something? You experienced doing it. Maybe what you learned came to you in a dream? You experienced that dream. We learn – or at least we have the opportunity to learn – through our experiences. Indeed, it is the only way we do learn.

What then to make of a book that focuses on experiential learning in international business as though this represented some unique pedagogy? The answer, of course, is that inserting ‘experiential’ before learning leads us to focus on the nature of experience that learners have and what they subsequently do with that experience. It may also lead us to exclude a range of activities typically associated with learning – lectures, readings, and the like – and to focus on activities that often include interactions with others or what might be called ‘learning by doing.’

How we learn is also part of the learning. Listening to a lecturer’s voice, turning a book’s page, taking in a video screen, and everything about each of those settings shapes how we learn. Recognizing that all learning is experiential and focusing on the totality of each experience open up the possibility of a much broader range of experiences for inclusion as ‘experiential learning’ opportunities.

Many, if not all of the chapters in this book, draw heavily upon Kolb’s (1984) seminal work for their theoretical foundation. Kolb (1984) describes a process for experiential learning that involves four steps – concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation. This chapter focuses particularly on delineating elements of the experience that impact its transformative potential. The intent in doing so is to broaden our approach to experiential learning in international business education.

The premise for this intention is that the cognitive, attitudinal, and behavioural requirements for people working in a global business context are such that mere education about international business is insufficient. Rather, a transformation is required (Osland & Bird, 2013) to fully develop global managers. Experiential learning approaches offer the greatest transformative potential. However, to leverage that potential, educators must be more attentive to the design and delivery of experiences.

This is not to suggest that the other three steps in Kolb’s learning process model are of lesser importance. There can be no doubt that each is important, but their efficacy is constrained by the quality of the experience in the initial step. If the experience is lacking in substance, then by necessity there are limits to how much can be drawn out through reflective observation, how well abstract conceptualization can capture what was experienced, or what type of active experimentation can be developed.

Thinking about learning experiences

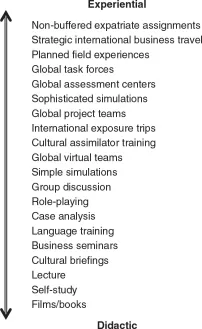

Perhaps the most common way to think of experiential learning is to consider it in contrast to didactic learning. Figure 1.1 provides a typical representation of pedagogies with experiential on one end and didactic on the other. In this instance, the pedagogies focus on those frequently considered in the context of international business or intercultural competency development. Using a didactic–experiential continuum, it’s possible to position each of the experiential exercises and activities described in the chapters of this handbook relative to the endpoints and to one another. For example, the Jackson et al. (Chapter 44, this volume) documents a study-abroad experience that would be closer to the experiential endpoint than would the experience described by Taras and Ordenana (Chapter 9, this volume).

Use of the didactic–experiential continuum, however, constrains our ability to understand the potential impact of the experience because it focuses only on the pedagogical approach and not on a critical component of the learning experience, one that is critical for the next phase in Kolb’s model, observational reflection. As Bennett and Salonen (2007: 46) have noted, ‘Learning from experience requires more than being in the vicinity of events when they occur; learning emerges from the ability to construe those events and reconstrue them in transformative ways.’

Figure 1.1 Scale of pedagogy from didactic to experiential

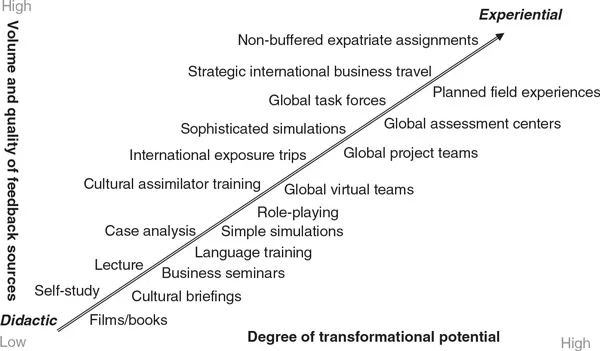

It is difficult to reflect well relying solely on information from oneself. Input from other sources, particularly feedback, can significantly augment one’s own observations, thereby improving the construal effort. Figure 1.2, adapted from Oddou and Mendenhall (2013), juxtaposes the didactic–experiential continuum in terms of two axes, degree of transformative potential versus volume and quality of feedback sources.

The underlying assumption embedded in this figure is that as one moves up the continuum there are increases in both the transformative potential of the experience – what Oddou and Mendenhall (2013) call ‘experiential rigor’ – and in the volume and quality of feedback from other sources. Though a reasonable assumption, there are a number of factors that likely influence the extent to which this is actually the case. There is no guarantee that other sources of feedback will necessarily be available, or, more importantly, that individuals will seek information from those sources. To paraphrase Bennett and Salonen (2007), it’s not enough to be in the vicinity of experiences when they occur, one must also access the observational sources attached to those experiences. Beyond making use of more and varied informational and feedback sources, there are also a number of factors that likely influence the transformative potential of the experience itself. These are considered in the following section.

Figure 1.2 The intersection of transformative potential and feedback for learning experiences1

The building blocks of transformational potential

The specific nature of various international business experiences is critical to the development of global managerial capability. The transformative potential of each experience can be understood in terms of four elements (Osland & Bird, 2013). Experiences with higher levels of these elements hold greater potential for learning and transformation.

One dimension along which experiences may differ is in their degree of complexity. This element of experience captures the extent to which a given experience incorporates aspects that are multi-layered or multifaceted. Experiences that are complex in this way create the possibility of multiple interpretations or competing explanations. Consider a Brazilian manager who must conduct a performance review with a German direct report in English. The interplay of languages and cultures alone makes this a far more complex event than a similar experience with a Brazilian direct report. To navigate this experience successfully, our Brazilian manager must grasp myriad cultural elements, accurately receive and convey nuanced meanings, and act with the necessary behavioural flexibility and discipline required by this situation. More complex experiences hold greater transformative potential because multiple layers and multiple facets generate a larger volume of information available to work with. Moreover, there is more that can be done with a larger volume of information, in particular the adoption of differing perspectives or the exploration of differing explanations.

It is also often the case that complex experiences, because of the richness of information they contain, can be revisited over time. When combined with learning from subsequent experiences, new layers of the experiences may be unearthed and new insights may be extracted. Particular complex experiences may serve as a source of ongoing learning over decades.

Affect attends to the degree of emotion that is present in or stimulated by an experience. Experiences characterized by higher levels of emotion, be they negative or positive, have greater transformative potential. Be it ‘real’ or simulated, an experience can elicit strong emotion – for example, frustration, joy, irritation, anger, or sympathy. An experience such as exploring a new culture may evoke intense feelings of excitement and joy that accompany concentrated discovery and learning. Feelings of frustration or helplessness may surface when struggling to communicate in another language. More affective experiences have more transformative potential because the strong affective element allows them to be recalled more vividly and over a longer duration. Strong emotions are accompanied by the release in the brain of chemicals such as adrenalin that aid in the forging of new and durable neural synaptic connections that aid recall. Consequently, emotionally powerful experiences are more accessible for subsequent reflection. An additional consequence is that such experiences may serve as triggering mechanisms for recalling other experiences.

In an experiential event, intensity involves the degree to which the experience requires concentrated effort or focused attention. For example, participating in a high-stakes international negotiation with a short deadline has a higher degree of intensity than fact-gathering as part of developing a market entry plan. The context of the negotiations requires participants to stay focused on the task at hand and to concentrate their efforts by acting quickly and efficiently. The more intense the situation, the more compelling is the need for attention. More intense experiences possess more transformative potential because heightened attention increases the probability of taking more information, particularly more context-specific information. In turn, a greater volume of context-specific information increases the likelihood of enhanced pattern and cue recognition, thereby facilitating sense-making.

The final element is relevance, which refers to the extent to which an experience is perceived as relevant to an objective or value important to the individual. More relevant experiences possess greater transformative potential because experiences framed as such are likely to elicit higher levels of attention and information gathering. Relevant experiences are also more easily placed into an existing schema and, consequently, more likely to elicit sense-making behaviour. This is also likely to be a consequence of relevance evoking a greater motivation to learn and understand the experience. As with the other elements, more relevant experiences are more likely to be recalled for reflection purposes.

It is also important to note that relevance is distinct from the other three elements in that, of the four, is it the only one that is separable from the experience itself. The objectives and values that an individual perceives as important may shift over time, causing that person to reassess the significance or triviality of a given experience or to view the experience in a different light. The relevance may also shift with the addition of new information. For example, an interaction with someone may seem trivial in the moment and then afterward become significant when it is learned that the person is important, for example, the president of a potential client company.

Taken as a set, these four elements provide a mechanism whereby every experience can be evaluated with regard to its transformational potency. Simple, routine experiences lack transformative potential because they frequently lack complexity, affect or intensity and are not seen as relevant or meaningful. By contrast, singular events characterized by multiplicity and multi-facetedness, intensity, strong emotion, and high relevance possess high transformational potential.

Among the most powerful experiences that many people have is a sojourn and immersion in another country or culture. The step out of the familiar into the unfamiliar; the challenge of making sense of what’s going on around oneself; and the violation of one’s cultural norms with regard to beliefs, values, attitudes, artefacts, and behaviours introduce extraordinary levels of complexity. At the same time, the initial exploration and then subsequent need to adapt and to function in the new culture often elicit a range of powerful emotions – from exhilaration to fear to frustration or anger to deep calm and well-being. Such experiences are often characterized by intensity, such that the period of initial entry appears to unfold both simultaneously rapidly and slowly – as though year has been packed into a month and a month seems like a lifetime.2 And often the need to adapt and adjust to get on with life lends a powerful relevance to much of what is experienced. Osland (1995) documents in great detail the transformational power of the expatriate experience.

The transformational potency of experiences can be diluted or even cancelled out by introducing moderators that dampen or buffer the experience. In some cases, the experiences are buffered by how the experience is structured. For example, a behavioural simulation such as Bafa Bafa can be made less potent by providing too much instruction or by too much intervention on the part of a facilitator. In other cases, individuals themselves may introduce buffers or dampening effects. Take the case of students on a study-abroad programme who choose to eat only in the school cafeteria, never venturing out to dine in local establishments.

It may also be the case that some experiences are neither novel nor challenging enough to foster transformational change. Finding the right balance of novelty and challenge requires careful consideration of the participants and their level of experience, preparation, and maturity. Graduate students are often capable of tackling more challenging experiences than u...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on Contributors

- Part I: Theories and Concepts of Experiential Learning in International Business/International Management

- Part II: Examples of Experiential Learning Projects in International Business/International Management

- Index