- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

How we address one another says a great deal about our social relationships and which groups in society we belong to. This edited volume examines address choices in a range of everyday interactions taking place in Dutch, Finnish, Flemish, French, German, Italian and the two national varieties of Swedish, Finland Swedish and Sweden Swedish. The chapter 'Introduction: Address as Social Action Across Cultures and Contexts' is oepn access under a CC BY 4.0 license via link.springer.com.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Address Practice As Social Action by C. Norrby, C. Wide, C. Norrby,C. Wide in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Negotiating Address in a Pluricentric Language: Dutch/Flemish

Roel Vismans

Abstract: Dutch is a pluricentric language: in Europe, it is spoken in two different countries (the Netherlands in the north and Flanders, Belgium, in the south) with differing linguistic norms. Vismans investigates what happens when the northern and southern Dutch address systems meet. His data come from in-depth radio interviews between Dutch journalists and Flemish academics. In a qualitative analysis, he tracks the development of the relationship between the two speakers and their use of address forms, as well as other markers of (in)formality. The analysis also takes into account other possible factors affecting the interaction (age, gender, residence in the other country) and pays special attention to speakers’ commentary on the variation between familiar and formal second-person pronouns.

Keywords: Dutch; pluricentric language; address pronouns; radio interviews

Norrby, Catrin, and Camilla Wide, eds. Address Practice As Social Action: European Perspectives. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015. DOI: 10.1057/9781137529923.0007.

1Introduction

This chapter investigates what happens when the northern and southern Dutch address systems meet in interactions between a northern and a southern speaker.1 Since the late 1950s, Dutch pronominal address forms have been on the move, as they have in other languages. There has been a gradual shift away from the traditional non-reciprocal power semantic (Brown and Gilman, 1960) towards a reciprocal system in which the formal pronoun is used to express distance and the informal pronoun to express common ground (for example, Clyne, Norrby and Warren, 2009). This shift was documented for Dutch by, among others, van den Toorn (1977, 1982) and is studied in-depth by Vermaas (2002; for a more recent study, see Vismans, 2013a). These and the vast majority of other studies of (changes in) the modern Dutch address pronouns are concerned with Dutch spoken in the Netherlands. However, Dutch is a pluricentric language – that is, a language that is spoken in two or more different, relatively self-contained jurisdictions whose linguistic norms may differ (compare Clyne, 1992). One of the characteristics of Dutch as a pluricentric language is that the use of address pronouns in its two main centres, the Netherlands and Flanders in Belgium, differs considerably.2

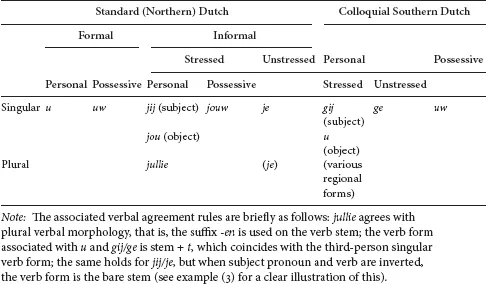

The standard (northern) address forms comprise a formal pronoun (u), which can be used both in the singular and plural, and separate singular and plural informal forms. The singular informal forms have the most complex morphology with a salient distinction between stressed forms (jij, jou, jouw) and an unstressed forms (je), and the unstressed form doubles up as generic/impersonal pronoun. Whereas formally the southern standard language has the same forms, and non-dialectal colloquial speech in the north also follows the standard pattern, colloquial southern Dutch does not distinguish between T (informal) and V (formal), but only has the singular pronoun gij (unstressed ge) with the oblique and possessive forms u and uw, and there are regional variants of the plural pronoun. The full paradigm for both standard (northern) and colloquial southern Dutch is given in Table 1.1.

These regional differences in forms and their use can give rise to misunderstandings when northern and southern speakers meet. This chapter therefore aims to investigate the use of address forms and their interpretation in conversations between Dutch and Flemish people. The data for this research are based on three long interviews between a Dutch journalist and a Flemish academic. The chapter opens with some reflections on the status of Dutch as a pluricentric language and the role of address in this. The interviews and their method of analysis are then described, followed by an analysis of the data. The chapter concludes with a discussion of the study’s findings.

TABLE 1.1 Address pronouns in standard (northern) and colloquial southern Dutch

2Dutch as a pluricentric language

The Dutch language area is discontinuous. In Europe, it comprises the Netherlands and Flanders, the northern half of Belgium. In South America, Dutch is the official language of Suriname and one of the official languages in the Dutch Caribbean islands Bonaire, Saba and St Eustace, as well as in three independent islands: Aruba, Curaçao and the southern half of St Martin (the other half being French). However, virtually all the literature on Dutch as a pluricentric language concentrates on the relationship between the two European varieties, and given the nature of this chapter we will also focus on European Dutch.

The socio-political setting of Dutch in its two jurisdictions in Europe differs considerably. In the Netherlands, where it is the dominant national language, three regional languages have been recognized within the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages, with Frisian at the highest level of recognition, and Low Saxon and Limburgish at a lower level. In Belgium, Dutch is one of three official languages alongside French and German. Since Belgium has not signed the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages, the country has no recognized linguistic minorities.

In 1980 Belgium and the Netherlands formed the Dutch Language Union (Nederlandse Taalunie or Taalunie for short), a unique international treaty organization with effective linguistic sovereignty over Dutch. With Belgian federalization in 1993, the Flemish Community took over responsibility for the Dutch language in Belgium and Belgium’s seat in the Taalunie. In 2004 Suriname acceded to the Taalunie as an associate member. Implicitly the Taalunie recognizes that Dutch is a pluricentric language, for example, where it defines standard Dutch (Taalunie, 2012; translation by author):

Incidentally, [standard Dutch] is not the same everywhere. You may hear some words or expressions in the Netherlands, but not in Belgium or Suriname. The pronunciation is also different in those three countries.

In codified standard Dutch, differences between north and south are largely limited to pronunciation and vocabulary. Recent phonological studies have shown, for example, significant differences in articulation rate and speech rate (Verh...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction: Address as Social Action Across Cultures and Contexts

- 1 Negotiating Address in a Pluricentric Language: Dutch/Flemish

- 2 Communities of Addressing Practice? Address in Internet Forums Based in German-Speaking Countries

- 3 At the Cinema: The Swedish ‘du-reform’ in Advertising Films

- 4 Address and Interpersonal Relationships in Finland–Swedish and Sweden–Swedish Service Encounters

- 5 First Names in Starbucks: A Clash of Cultures?

- 6 Address in Italian Academic Interactions: The Power of Distance and (Non)-Reciprocity

- The Last Word on Address

- Index