- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The mission UNESCO, as defined just after the end of World War II, is to build 'the defenses of peace in the minds of men'. In this book, historians trace the routes of selected UNESCO mental engineering initiatives from its headquarters in Paris to the member states, to assess UNESCO's global impact.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A History of UNESCO by Poul Duedahl in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Social History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Routes of Knowledge

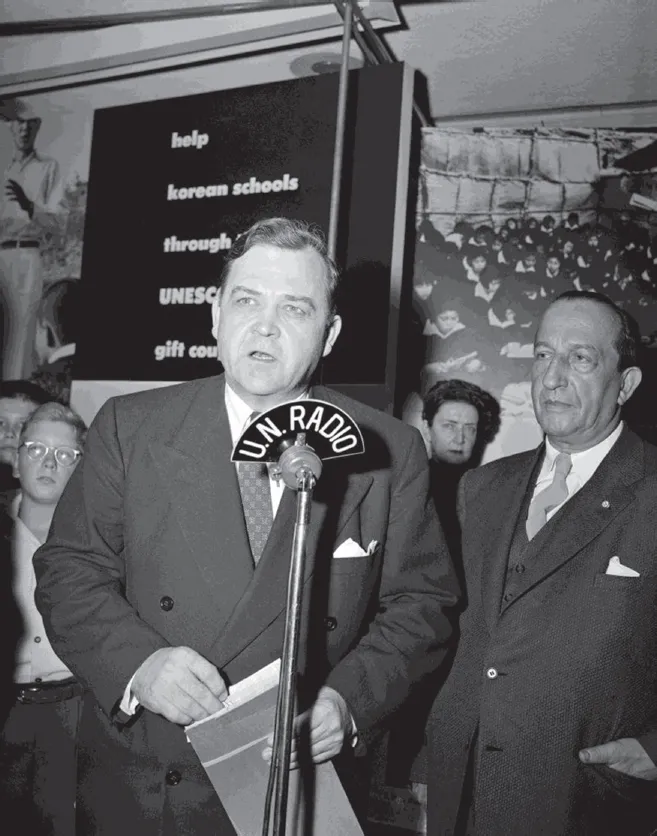

Figure PI.1 Director-General Luther H. Evans makes a radio broadcast in October 1954 during which he presents a gift for the UN Korean Reconstruction Agency. The collected funds were used to establish a UNESCO children’s ward at the Tongnae Rehabilitation Centre in Korea. (© United Nations)

The cornerstone in UNESCO’s extensive attempt to construct peace after World War II has been its ability to communicate with the world outside of its headquarters.

The instruments for transferring and sharing knowledge have been many. The organization has issued binding declarations and normative statements. It has opened field offices and sent experts to its member states. It is the only UN agency with national commissions, schools and clubs in the member states as a way of linking directly with civil society. It has cooperated with numerous NGOs that have helped implement its programs. It has been preoccupied with specialized activities in the field of mass communication and it has worked on ensuring the free flow of information, including knowledge from the organization itself and to the surrounding world. Some of these activities have had a big impact, others hardly any, but all of them have been essential to UNESCO’s communication strategy.

Right from the beginning, UNESCO has been particularly engaged in the use of new media and their ability to reach a wider public. That includes radio broadcasting, TV, film and other audiovisual media as means to spread knowledge – for example, as part of its fundamental education programs. It has published magazines of which the most widely distributed was The UNESCO Courier, which in the 1960s was published in 35 different languages and for which the print run was 1.5 million. Not least has the organization taken quite a considerable number of initiatives in which books were at the center. Not only have books constituted a natural extension of UNESCO’s work on fundamental education but the prevalence and use of printed literature has over time made it the major tool used by the organization in its efforts to develop and influence cultural and educational awareness, and to create “peace in the minds” of men and women.

1

Popularizing Anthropology, Combating Racism: Alfred Métraux at The UNESCO Courier

Edgardo C. Krebs

I

On 18 May 1945 the Swiss-born ethnographer Alfred Métraux (1902–1964) wrote the following letter to his wife, Rhoda, from Tübingen, Germany:

My darling, This afternoon I have been deeply shaken by the sight of a group of Jewish girls who were coming back from one of the death factories – Auschwitz. How to describe them? Imagine corpses who had emerged from the grave. There was around these ambulating skeletons something out of this world. A woman whom I thought to be about 50 turned out to be 23. As she collapsed and was obviously dying, she was taken away in a hurry. I talked with the others. No sooner one of them began to mention the horrors of the camp, the others started to cry and the girl became hysterical. They had their tagged numbers tattooed on their bodies. Darling, I have seen that – most of them had been branded like cattle on the throat or on their shoulders. They were taken to rest in a room with beds on which they threw themselves sobbing and laughing. The few things that they were able to tell (sur)pass the published reports. They were thrown to dogs, forced to witness the burning of other women … They screamed when they mentioned what happened to the children. The whole incident was so awful that there was not a person present who did not have tears in his eyes. I had to leave because I was breaking down. Yesterday I saw men coming from the same place. Often they also cry when they start to tell about happenings there. The worst of all is that the Jews are still afraid and expect ill treatments or abuses. Alas, their fears are not entirely unfounded. Anti-semitism is strong among the people I have seen lately. When you see the logical result of anti-Semitism, you begin to sense it as a vicious and murderous attitude which must be combated. Some of the injustices which I mentioned in my last letters are being corrected, but not all and I still witness a few incidents which revolt me. If things do not change quickly in Europe, more blood will flow very soon. I cannot stand the idea that all the suffering of these people has been in vain. Fascism is far from dead. It has poisoned the minds, even of those who come back from the German inferno.

The experiences of this trip have a deep effect on me. It will be difficult to return to library work and the S.A. Indians. I would like to help these friendless people who are coming out of 5 years of serfdom and humiliation to discover that nobody wants them and who find out that their saviors feel about them very much as the Germans did. I am beginning to think that Spaniards, Poles, and Italians are the martyrs of Europe, those to whom our sympathy should go. Then there is the German problem. Eastern Europe now appears somewhat like it was in the 13th century when the Mongols were loose or during the black plague. From Germany come millions of people with tales of horror, confusion, murder and looting … I am not gay, somewhat sad, but also immensely happy to be plunged in this drama and for once in my life I have an intimate contact with so many people within my own culture. I am amazed at the decency and simple greatness I found in peasants and workers. They are the only ones who are really human and sensible. The rest is often dried up or rotten. I wish I had an UNRRA (United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration) job … Tell Margaret Mead about my experiences and ask her whether she could not recommend both of us for some relief work in central Europe. In the evenings, I walk in my medieval city and read Goethe. Your photograph is constantly under my eyes and I look at it often – I even talk to it.1

II

Together with an eclectic group of people, especially recruited for the task, Métraux was part of the Morale Division – a component of the US Strategic Bombing Survey (USSB). The USSB’s overall mission was to estimate the damage done by Allied bombing, first in Germany and later in Japan. The categories and areas addressed by the survey were organized into 12 divisions. Most of them dealt with the material damage inflicted on industry, roads, railways and the general capacity of the Germans to keep their machinery of war in operation. The Morale Division was charged with estimating the human costs of strategic bombing or, in the official terminology, “The Effects of Strategic Bombing on German Morale”. The recruits for this mission had to speak German, and to possess certain qualities as interviewers and writers. Fluent in German and a seasoned ethnographer, Métraux was perfectly suited to the job. In April 1945 the Morale Division set off for Europe, where it followed the advance of the Allied Forces in Germany, interviewing German civilians and soldiers.2

Some 13 years earlier, another war, fought very far from Europe, had also trapped Métraux as a witness. In 1932, Paraguay and Bolivia clashed over portions of the Chaco, backed by France and Germany, respectively.3 Métraux was doing fieldwork at the time among Toba-Pilaga, Wichi and Chulupi Indians. His distress at what he observed – the plight of the Indians, who fell as collateral damage and were in a constant state of flight, crossing rivers and frontiers to avoid murderous raids by soldiers of both armies, and even bombing campaigns not indicted by any image as powerful as Picasso’s Guernica – produced a crisis in Métraux. He disappeared for a couple of weeks while contemplating whether he should quit anthropology and become a missionary. The Anglican Mission in the Chaco was dealing with practical matters: fixing broken limbs, providing healthcare and providing a safe haven.4 After those two weeks in the wilderness, Métraux decided he could never be a missionary. Instead he wrote a letter to General Juan B. Justo, then the president of Argentina, proposing the re-creation of an old colonial institution – that of Protector of Indians – and to place him in charge.5 As the founding director of the Institute of Ethnology at the University of Tucuman, he had the standing and the contacts to propose such a thing. The letter, a real report on the conditions of the Indians in the Chaco, was never answered.

In 1934–1935, Métraux participated as an anthropologist on a French-Belgian research mission to Easter Island, charged with the purpose of studying its impressive statues and the small surviving population of descendants of the original inhabitants. The island was under Chilean sovereignty but managed by a British sheep-farming company. Métraux was dismayed by the poverty of the locals, and by the fact that they were confined to just one village, Hanga-roa. They could not access any other points of the fenced-off land, including the areas where the moai stood, facing the ocean or collapsed and partially buried on the ground. He was struck by the injustice, and very critical of the imposed political and economic system responsible for it. Free himself to roam the island, he managed to take his local assistants with him and photographed them posing at the top of the statues or standing in front of rocks inscribed with ancestral petroglyphs. Métraux’s scientific mission was successful. He was able to clarify conclusively longstanding questions about the origin of the human presence on the island, and the construction and meaning of the moai. However, in the popular book he wrote in 1941 about the island, he also described the living conditions of the native inhabitants and stated that after the European definitive occupation in the second half of the 19th century, Easter Island “asked nothing more of us but the fulfillment of a simple human duty: that the persons and dignity of the descendants of the Polynesians who carved the great statues and engraved the tablets should be respected by their new masters”.6

Even though Métraux’s original expertise was in the history and ethnology of South American Indians, a short stay in West Africa in 1934 on the way to Easter Island had opened up for him what was to become his other scholarly passion: the study of African cultures in the New World.7 This affinity found an outlet in the early 1940s when he visited Haiti, a country where he returned repeatedly and about which he produced what, for his colleagues, in particular the Haitians, still remains one of the best ethnographies of voodoo available.8 The influential Melville Herskovits, a Franz Boas student who created the first Department of African Studies in the USA at North Western University in Chicago, promoted his younger colleague. He wanted Métraux to be the person hired by The Carnegie Corporation to do the research and write the report that would later be known as an American Dilemma.9 Métraux was seriously considered, and it was one of the great disappointments of his life – one shared by Herskovits – that Gunnar Myrdal was chosen instead.

When, in 1947, Métraux joined the staff of the UN at its headquarters in Lake Success, New York, he had resolved a personal question which troubled him repeatedly while serving in Germany as a member of the Morale Division: “What will be my future? Again a scholar in a peaceful room or man of action in other fields. I am torn between the two desires, the eternal conflict of my life.”10

III

When, in 1950, Métraux replaced the Brazilian scholar Arthur Ramos as Head of the Division for the Study of Race Problems in UNESCO’s Department of Social Sciences, he brought to the task a wealth of relevant scholarly expertise and personal experience. The force behind the creation of this program was an imperative to address the ideology of racism. The extermination camps of the Nazis were the most barbaric evidence of the consequences of marrying racial prejudices with politics and biology. The UNESCO program, in particular its first statement on race of 1950, dismantled all pretenses that there was a biological basis for racism. Race and racism, it established, were cultural constructions.11

The program was a direct offshoot of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. This landmark document was problematic from the very beginning. As a “declaration” it lacked the legal instruments to be enforceable. It was also, from a juridical perspective, an attempt at synthesizing beliefs of different cultures. Its main architect, the French jurist René Samuel Cassin, worked indefatigably behind the scenes, and in the spotlight, to will it into existence.12 To provide a philosophical basis for this enterprise, in 1948, UNESCO organized an international symposium under the direction of the French Thomist philosopher Jacques Maritain. He realized that “the problem of Human Rights involves the whole structure of moral and metaphysical (or anti-metaphysical) convictions held by each of us”. Would a consensus be possible, he wondered, among men “who come from the four corners of the globe and who not only belong to different cultures and civilizations but are of antagonistic spiritual associations and schools of thought?” The solution for him was to agree that the declaration should be “given an approach pragmatic, rather than theoretic...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Notes on Contributors

- Introduction: Out of the House: On the Global History of UNESCO, 1945–2015

- Part I: Routes of Knowledge

- Part II: Rebuilding a World Devastated by War

- Part III: Experts on the Ground

- Part IV: Implementing Peace in the Mind

- Part V: Practising World Heritage

- Index