eBook - ePub

Structural Revolution in International Business Architecture, Volume 1

Modelling and Analysis

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Structural Revolution in International Business Architecture, Volume 1

Modelling and Analysis

About this book

Most of the established theories of economics, particularly of international trade, became obsolete in the new world trade and production architecture. How, in these new circumstances, will host nations organize their economic resources? This book analyzes some prominent countries in the world to examine the issue.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Structural Revolution in International Business Architecture, Volume 1 by Victoria Miroshnik,Dipak Basu in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business Strategy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Meaning of Structural Revolution

Multinational Companies and National Economies

During the colonial period, and even after the Second World War, state powers were used to provide security for the interests of multinational companies. Since the 16th century, there have been imperial conquests by Western European countries, and as early as the 7th century by Islamic countries, to promote their business interests and to capture essential sea and land routes for international business. Since the Second World War, ‘regime changes’ have been used for the same purposes. The interests of the multinational companies and their governments were identical in these imperialistic conquests. The impacts of these interventions on colonized countries are great social and economic upheavals, destructions of domestic industries, forced migration of people and devastating famines. Within ten years of 1757, when the East India Company acquired the contract to collect taxes in Bengal, one fifth of the population were wiped out. Nearly a million people were killed in 1973 in Chile in order to protect the interest of the American mining companies. At those times, some parts of these colonized countries, particularly in the coastal areas, benefited from the expansion of trading activities and participations in the global economy controlled by the multinational companies of the great colonial powers.

The rapid developments of the East Asian countries, including China, are mainly due to foreign investments. As a result, now developing countries are competing for foreign investments and offering more and more attractive terms to multinational companies. The slave trade, which used to be dominated by the Islamic, Arabic, Turkish and north African countries and sanctified by the Khalifas, was taken over by the Christian countries of Western Europe and blessed by the Popes.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank, and the World Trade Organization (WTO) have now replaced those Popes and Khalifas, creating and maintaining their shared motives and objectives to promote the interests of multinational companies in the area of trade. Just as the 19th-century high priests of the Age of Enlightenment, John Stuart Mill, David Ricardo and Jeremy Bentham of the East India Company, did to justify colonialism in the name of free trade, the IMF, the World Bank and WTO promote services and investments but not people. They do so to create free flow of products and privatization of public industries, in order to promote the so-called ‘efficiency of resource use’ and to abolish any central planning of investment for the country. Promotion of free trade is the most important agenda. The IMF’s declared policy is to facilitate the balanced growth of international trade. However, the historical examples are against it. Free trade between India and the UK had ruined the domestic textile industry in India in the 19th century. Free trade between the USA and China has since ruined the established industries in USA. India’s trade deficit with China had reached around US$60 billion in 2014.

The WTO claims that it creates a rules-based system for the conduct of trade relations; but once again the historical experience in recent years has been very different. China has a variety of non-tariff restrictions and an artificially low fixed exchange rate to promote its exports. WTO is unable to do anything.

The Role of Trade Policy in IMF-Supported Programmes

The overall objectives of IMF-supported programmes are to achieve balance of payments stability and macroeconomic stability with a high level of economic activity. The reforms of the trade regimes generally mean removal of quantitative restrictions on imports and reductions of subsidies for exports to create a competitive atmosphere in the international trade system. The Extended Fund Facility (EFF) and the Poverty Reduction and Growth Facility (PRGF) are designed as both carrots and sticks. These provoke the liberalization of restrictions on trade flows and exchange rate systems and complement structural reforms to reduce the role of the government in the total economic activity (IMF, 1991).

The Trade Restrictiveness Index (TRI), developed by the IMF, gives a measure of the restrictive practices of a country’s trade policy. Countries are rated on their index of liberalized trade practices. According to the IMF and the World Bank, the rapid expansion of trade was the result of liberalization. However, fears are raised that trade has not accompanied real rate of growth for the domestic economies.

Extent and Focus of Trade Policy Conditions

This section examines the overall trends in structural conditions related to trade policy in IMF-supported programmes during the early days of globalization, 1987–99, based on the Monitoring of Fund Arrangements database (MONA). Data from MONA indicate that the structural conditions on trade policy reforms were relatively stable.

Effects on Employment Patterns

A strange result has emerged in Africa where, since the introduction of reforms, the percentage of the labour force working in formal sector jobs has declined, as a result of the reduced scale of the public sector and the relative inability of the countries in Africa to achieve higher growth paths (van der Hoeven and van der Geest, 1999). This is foreshadowed by the fact that African countries in general have implemented the structural reforms as suggested by the IMF, the World Bank and the WTO. Foreign domestic investment in English-speaking Africa, which is needed to provide the financial backing for the necessary structural changes, has not been forthcoming. Foreign investments are lacking and there is a low rate of domestic investment flows.

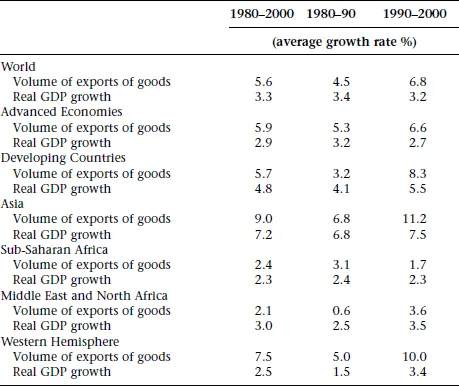

Table 1.1 Exports and Gross Domestic Product, 1980–2000

Source: Word Economic Outlook (World Bank).

Experiences are different in Asia where their high formal sector employment, employment in the manufacturing sector and, in South Asia, employment in the informal sector were impressive (ILO, 1996).

In Latin America, the cost of liberalization was high. As Lee (1996) points out:

The experience of Chile in the early 1980s illustrates that the output contracted by 23 per cent in 1982–93 and unemployment remained above 23 per cent for 5 years. Similarly the Mexican crisis of 1994–95 illustrated the devastating effect of wrong monetary and exchange rate policies.

Table 1.2 Sub-Saharan Africa: evolution of employment in the formal sector during the early adjustment phase (as percentage of the active population)

Country | 1990 | 1995 |

Kenya | 18.0 | 16.9 |

Uganda | 17.2 | 13.3 |

Tanzania | 9.2 | 8.1 |

Zambia | 20.7 | 18.0 |

Zimbabwe | 28.9 | 25.3 |

Source: UNILO.

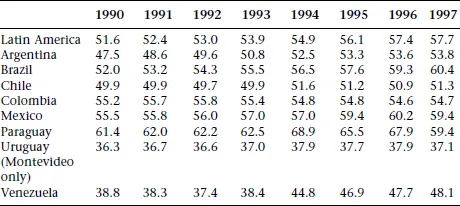

Table 1.3 Informal employment as percentage of labour force (non-agricultural) in early globalization in selected countries in Latin America

Source: UNILO (1998).

Despite positive growth rates, liberalization measures in Latin America have resulted in more and more insecure and low paid jobs in the informal sectors (Fanelli and Frenkel, 1995, 2003). Latin American workers are fearful of further liberalization measures (ILO, 1995).

Trade-off between growth and equity

There is an old argument that inequality is good for growth because higher level of inequality creates more savings from the higher income groups and, as a result, the growth rate will be higher. While that may be true in the initial level of liberalization, there is increasing evidence that inequality is not good for growth (Alesina and Perotti, 1994). Increasing equality means higher levels of demand for manufactured products and increased levels of education, leading to high levels of skilled manpower. Increased inequality also means increasing power of the oligarchs, which leads to demands for lower taxes and subsidies. These in turn can result in both fiscal deficits and inability of the poorer sections of society to create sufficient demands for a privatized economy (Persson and Tabellini, 1994) and are all growth destructive. Inequality can cause social turmoil and eventual destruction of a civil government, swiftly replaced by a military government. This may prevent governments from taking effective measures for economic growth (Stern, 1991). Macroeconomic policies can have emphasis on tax policies and on expenditure policies (Pyatt, 1993), with monetary policies playing only a lesser role, as tested by Keynes, which can bring social stability and growth. Active minimum wage policy, redistribution of the fiscal burden, targeted public expenditure and redistribution of ownership assets can all contribute a lot towards the goal of equality through growth. However, in reality this is not the case and, as a result, we are experiencing increasing social turmoil (UNDP, 1991; Khan 1992; Stiglitz, 1998).

The IMF and the World Bank’s programmes to liberalize the economy might have done serious damage to the fortunes of the poorer people of the countries receiving their funds and advice (Easterly, 2000). The poor have lost the advantages of subsidies and protected employments. They are mainly in the informal sector and the small scale low technology-oriented manufacturing sectors, which are under increasing attack from Chinese exports over which WTO cannot offer any protection.

World Poverty Trends over the Last Decade

Recent history, after the structural reforms, does not support the theoretical views given by the IMF, the World Bank and the WTO. The number of people living on US$1 a day or less fell from about 1.3 billion in 1990 to 1.2 billion in 1998. We concentrate on the income dimension of poverty, not the calorie consumption of the people, because in that situation there is no case for liberalization at all. To hide the real poverty rate, most countries, India for example, do not care anymore about the calorie content that makes up people’s consumption. Even the proportion of the population living in poverty—the poverty rate—fell a little, from 29 per cent to 24 per cent during the same period (1990–98). Poverty reduction performance was also extremely uneven. Poverty fell by the most in East Asia, to about 1.8 billion people. However, much of the reduction in poverty was in China, whose statistics are most unreliable. Poverty outcomes were much less impressive in other developing regions. Total numbers of people living under US$1 a day increased in all other regions. In South Asia, there was a decline of four percentage points in the poverty rates. Poverty rates never went down at all in Latin America, sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East and North Africa. Disaster struck in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, where countries moved away from socialism to a free enterprise system and real poverty returned after an absence of at least 50 years.

Has Globalization Increased Inequality between Countries?

It seems that globalization has increased inequalities between countries as well as people. In 1960 the average per capita GDP in the richest 20 countries in the world was 15 times that of the poorest 20. In 2000, rich countries were earning 30 times more per capita. Real incomes in the poorest 20 countries have stagnated since 1960, but have gone down in a number of countries. After globalization, in most cases, the poorer countries grew less rapidly than the richer countries.

Labour Market Developments

There is a causal link between the liberalization policy and labour market trends in the countries that adopted these adjustment processes. In Africa, for example, formal sector employment declined mainly because of the much reduced public sector and the repressed growth of the private sector, which failed to create alternative employment (van der Hoeven and van der Geest, 1999). Thus, the proposed aim of the liberalization process, to create more jobs in the formal sector, is still unfulfilled. With rich natural resources, and low wage rates, African countries have no excuse not to develop. However, despite implementing most aspects of the reform process they could not develop their economies. Foreign investments are coming mainly from China, which has never seriously embarked upon any liberalization programme; instead state planning is still the norm.

In South Asia there are strong indications that employment in the informal sector has expanded, but not in the formal sector (ILO, 1996). Also in Latin America, transitional costs of liberalization policies have been high. As Lee (1996) points out, ‘The experience of Chile in the early 1980s illustrates the severe effects of overshooting in terms of stabilization policy. Output contracted by 23 per cent in 1982–93 and unemployment remained above 23 per cent for 5 years’.

Changes in wage and income inequality increased in Asia in six out of 12 countries, Bangladesh, Indonesia, Thailand, China, Singapore and Sri Lanka; in Africa in four out of six countries, Nigeria, Tanzania, Kenya and Ethiopia: and in Latin America in nine out of 14 countries, Bolivia, Mexico, Argentina, Brazil, Panama, Venezuela, Guatemala, Honduras and Peru (World Bank, 1996).

The theory of liberalization suggests that liberalization means declining inequality, as trade liberalization will favour a country that has comparative advantage in the production of certain goods. Developing countries have the advantage of low cost labour (Berry, 1997). However, as the ILO (1996) have pointed out, in most countries that underwent the liberalization process the result was falling real wages and increasing poverty of the labour force, particularly in the privatized public sectors. The manufacturing industry tends to be dominated by large companies in the formal sector, where wages are higher but there are weak linkages to the small scale sector. Liberalization makes it easier to import capital goods and raises the demand for skilled labour (UNDP, 1997).

Amsden and van der Hoeven (1996) observed that the distribution between incomes from labour and capital in industry was shifted in the direction of capital in the 1980s. This has led to changes in consumption patterns and lifestyles, adding to inequity (Pieper, 1997; ILO, 1996). Liberalization has resulted in the decline of trade union membership, which has weakened the bar...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables

- List of Figures

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1 The Meaning of Structural Revolution

- 2 Tariff Policy and Employment Structure in the UK

- 3 Structural Reforms in China

- 4 Structural Reforms in India

- 5 Structural Reforms in Nigeria

- 6 Structural Reforms in Egypt

- References

- Index