eBook - ePub

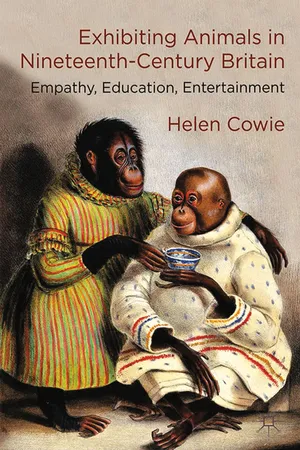

Exhibiting Animals in Nineteenth-Century Britain

Empathy, Education, Entertainment

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Exotic animals were coveted commodities in nineteenth-century Britain. Spectators flocked to zoos and menageries to see female lion tamers and hungry hippos. Helen Cowie examines zoos and travelling menageries in the period 1800-1880, using animal exhibitions to examine issues of class, gender, imperial culture and animal welfare.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Exhibiting Animals in Nineteenth-Century Britain by H. Cowie in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Lions of London

Is it not strange that one of the coldest animals in the Zoological Gardens is the otter? (Ipswich Journal, 11 February 1837)

In September 1823, an anonymous correspondent addressed a letter to the editor of the Morning Chronicle emphasising the urgent need for a zoological garden in London. The correspondent, who gave his initials as ‘C.T.’, hoped that his letter would draw public attention to ‘a subject which other nations have not thought beneath their notice’. A national zoological collection, C.T. explained, would be of benefit to Britain, both socially and scientifically, and would raise its international image. Now, moreover, was an ideal moment to found a zoo, since a project of this nature was well suited to ‘these times of peace and general improvement’.

Outlining the reasons why he favoured the creation of a zoological garden, C.T. cited a number of factors – scientific, social and humanitarian. Firstly, a zoo would advance the discipline of zoology by providing live animals for Naturalists to study, for ‘great as are the advantages to Naturalists in the collections of animals preserved by art, yet the advantages to be derived from the study of the nature and properties of the living animal are undeniable’. Secondly, a zoological garden would function as a place of public recreation and education by furnishing ‘the idle and ill-disposed’ with ‘objects to arrest their attention, and perhaps teach them to reflect’. Thirdly, a zoo would entertain ‘the more useful class of society’, fulfilling ‘the great political desideratum ... of keeping this important part of the community in good humour’ at a time when calls for electoral reform were growing louder. Fourthly, the creation of formal gardens would ensure better conditions for the animals than existed in menageries, providing, in turn, a more pleasurable viewing experience for spectators, as ‘surely ... it is more gratifying’ to see ‘the noble lion enjoying a capacious apartment open to the free air, or the unwieldy elephant stalking forth from his spacious habitation to roll himself in a pool of water’ than ‘to see these inhabitants of the forest or refreshing glade or sequestered lake moping away their melancholy lives in the hot unwholesome air of crowded rooms!’ Finally, the establishment of a zoological garden was necessary as a matter of national pride. While France, Britain’s neighbour and rival, already had an impressive zoological garden at the Jardin des Plantes, the best London could muster was ‘a few wretched animals shut up in the gloomy confines of our Tower of London’. According to C.T., it had ‘long excited the surprise of Foreigners and the regret of many of our enlightened Countrymen, that this nation possesses nothing deserving the name of a National Menagerie’. The time had surely come to rectify this situation, not least because Britain’s powerful navy, flourishing commercial connections and growing number of settlements overseas provided the means by which to do so. ‘Possessing ... settlements in the various quarters of the globe, in extent and power beyond any other nation ... [we enjoy] opportunities ... for collecting specimens of the various animal tribes of other countries.’1

It took five years for C.T.’s vision to be realised through the foundation of the Gardens of the Zoological Society (the present London Zoo) in 1828. If his letter had little immediate impact, however, its content nicely encapsulates the main reasons for establishing zoological gardens, not only in London, but also in other British cities, where the tropes of animal welfare, rational recreation, social well-being and national pride surface again and again in prospectuses and newspaper reports. To have a zoological garden became a symbol of material wealth, social consciousness and moral progress. The creation of zoological gardens also formed part of a broader movement to open museums and other sites of education to the middle and lower classes, serving a public beyond the cultured elite.2

While other cities would copy London’s Zoological gardens, it was in the British capital that the idea first took hold. We therefore begin our study of exotic animal exhibitions in the metropolis, which, even before London Zoo came into existence, was home to an eclectic range of zoological displays. Here I discuss where people could view foreign beasts and birds, how their conditions of display changed during this period and what value and meanings were ascribed to them. The chapter starts by looking at fixed menageries and other sites of exhibition in the early nineteenth century. It then moves on to look at two key zoological establishments: the Gardens of the Zoological Society in Regent’s Park and the less well-known Surrey Zoological Gardens in Walworth.

Sites of exhibition

Though London had no zoological gardens until 1828, it was by no means bereft of exotic animals. Travelling shows provided a venue where people of all classes could view rare beasts, either singly, or, increasingly, en masse (see Chapter 3). In addition to these itinerant exhibitions, Londoners could see exotic creatures in a number of other locales, some permanent, others more temporary in nature. Most notable among the former were two static menageries whose contents were open to the public from the eighteenth century. The first of these, the Tower Menagerie, was a royal collection, dating back to the Middle Ages. The second, the menagerie at Exeter ’Change, was formed in the mid-eighteenth century for explicitly commercial purposes.

Founded in the thirteenth century, the Tower Menagerie was Britain’s oldest zoological collection and functioned principally as a glorified repository for the various exotic beasts bestowed upon the monarchy as diplomatic gifts. Originally located in Woodstock, near Oxford, the collection was moved to a wing of the Tower of London under Henry III (1207–1272). The menagerie remained in this location until 1831, when it was transferred to the Gardens of the Zoological Society. From the seventeenth century it was open to the public, who could view it for one shilling.

Though the quality of the Tower Menagerie fluctuated over the years, depending on the enthusiasm of the reigning monarch, it usually consisted of at least a handful of big cats, mainly lions and leopards. Other more unusual inmates also occasionally featured in the collection. In 1252, for instance, records show that the sheriffs of London were ‘commanded to pay 4 pence a day for the maintenance of a polar bear’, which the following year required ‘a muzzle and chain’ to hold him ‘while fishing or washing himself in the River Thames’. Three years later, in 1255, the sheriffs were ‘directed to build a house in the Tower for an elephant which had been presented to the King by Louis King of France’.3 When keeper Alfred Copps published a list of the animals in the collection in 1822, he enumerated over thirty beasts, among them a ‘striped hyena’, a ‘cinnamon bear, presented by the Hudson’s Bay Company’ and ‘a pleasing variety of parrots, parroquets, doves, manakins, nutmeg birds etc.’4 Some of these had been donated by royalty and others purchased by Copps himself.

The diarist Gertrude Savile offered a first-hand account of a visit to the collection in the early eighteenth century. Visiting the Tower on 17 August 1728, Savile described how the menagerie then consisted primarily of big cats and birds of prey, namely six lions, ‘a Tiger, a Leapard [sic], a Panther, 2 Eagles and a Vulture’. The star exhibits, two newly-born lion cubs, were on view in one room, where Savile watched them being nursed by two women ‘by a fire Side ... stifleing hot [sic]’. They were ensconced on the laps of the women, ‘wrap’d in little Quilts’ and drinking milk. During the same visit, Savile admired ‘2 [lions] together that were whelp’d here of 3 Year old, in a Den – a He and a She (which I saw a year and a half ago)’, which were ‘tame enough to let the Man Stroak [sic] them’, and two more year-old cubs ‘about as big as a pretty large dog’, which were running ‘loose in a Room’. The diarist apparently enjoyed her encounter with the animals, declaring herself ‘much pleas’d’ with the lions, particularly the young ones.5

From the early nineteenth century, the Tower Menagerie co-existed with another royal animal collection: the menagerie at Sandpit Gate. Situated in the grounds of Windsor Castle, 22 miles outside of London, this menagerie was also accessible to the wider public, who could see it for free on Mondays and Saturdays. Sandpit Gate was much more roomy than the Tower, and, in the view of one journalist, considerably more pleasant to visit, for ‘in this menagerie the animals are not pent up in miserable dens, but have large open sheds with spacious paddocks to range in, water in plenty and spreading trees to shade them from the midday sun’. While the Tower concentrated mainly on ferocious carnivores, which required strong cages, most of the animals in the Windsor collection were herbivorous, allowing for a more pastoral layout. In 1829, the menagerie’s inmates included antelopes, deer, kangaroos, zebras, ostriches, emus and a sickly male giraffe presented to George IV by Muhammad Ali Pasha of Egypt.6

The other major zoological collection in early nineteenth-century London was the menagerie at Exeter ’Change. Founded in the late 1780s, this impressive assemblage of animals was housed in the upper apartments of a building in the Strand, above a concourse of shops.7 Unlike the Tower Menagerie, which began as a royal collection, Exeter ’Change operated as an overtly commercial venture, and was designed from the outset to make a profit. The menagerie survived in its original location until 1829, when it was transferred to a more spacious building in the King’s Mews, Charing Cross; it was formally disbanded two years later. During its forty-year existence, the exhibition had three different owners: Gilbert Pidcock (1789–1810), Stefano Polito (1810–1818) and Edward Cross (1818–1831).

Exeter ’Change was the prime site for viewing exotic animals in London at the turn of the nineteenth century, attracting visitors with a constantly changing range of beasts. In 1790 the menagerie featured ‘that renowned Animal the Rhinoceros’ and ‘three stupendous ostriches, lately arrived from Barbary’.8 In 1793 it boasted ‘the most beautiful ZEBRA ever seen in Europe’ and in 1831 it contained a ‘fine’ and ‘very hearty’ baby camel, said to be the only one born in Britain.9 Several monstrosities and manmade wonders were also exhibited alongside these exotic species, including a cow with ‘two heads, four eyes, four ears and four nostrils’, and, in the aftermath of ‘The Terror’ of the French Revolution (1793–4), ‘a model of the Guillotine, or French beheading machine’.10 The menagerie’s most famous inmate, the elephant Chunee, resided in the collection for 17 years and was a great favourite with Londoners. He sadly grew unmanageable as he reached maturity and was destroyed by a firing squad in 1826.11

The creatures in Exeter ’Change were displayed in tiny cages. The walls of the building were ‘painted with exotic scenery’ to conjure images of the Tropics and visitors appear to have enjoyed quite intimate contact with the beasts, from stroking the ‘gentle zebra’ to caressing the newly-born lion cubs.12 For those spectators who wanted to learn more about the animals, printed pamphlets were available for purchase at the entrance, containing descriptions of the different creatures in the collection. In 1820, for instance, proprietor Edward Cross published a Companion to the Royal Menagerie, Exeter ’Change, to ‘attract the attention of the youthful visitor to this most pleasing and important branch of natural history, and to draw the inquiring, unbiased mind to study the characters of animated nature herself, as these rare specimens present’.13 Keepers would also be on hand to deliver short lectures on the different beasts, though how educational these were is open to question. A satirical account of a visit to the menagerie in the periodical the Fancy mocked the ignorance of the zoological guide, who spoke with a strong Cockney accent – ‘that there is the vunderful Hafrican helephant’ – and regurgitated many old myths about wild beasts, from the chameleon’s ability to live on air alone to the belief that the bear ‘licks his cubs into shape with his tongue’.14

A contemporary print by Rudolph Ackermann (Figure 1.1) gives us a sense of how the exhibition might have looked. Here we can see what appears to be a relatively small wooden-floored room with cages arranged around the periphery. The elephant’s enclosure at the far end of the room is so cramped that the animal is barely able to turn around. The cages of the lion and tiger are hardly more generous in their dimensions, allowing their inmates to do little more than lie torpidly behind bars; the monkeys’ cages, stacked on top of the latter permit almost no movement. The painted tropical foliage mentioned in verbal accounts is depicted immediately above the top storey of cages, though this is hardly sufficient to give any air of naturalness to the scene. The visitors flock around the exhibits, looking curiously at the animals, and receiving instruction from the keeper. A party in the centre of the composition stares and points excitedly at the beasts as its members decide which to approach. Their attire and physique – bonnets, top hats, canes, and, in one case, protruding stomach – suggest that they are upper or middle class, the one s...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- 1 The Lions of London

- 2 Zoo, Community and Civic Pride

- 3 Elephants in the High Street

- 4 Animals, Wholesale and Retail

- 5 Seeing the Elephant

- 6 Cruelty and Compassion

- 7 Dangerous Frolicking

- 8 In the Lions Den

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index