eBook - ePub

Nationality, Citizenship and Ethno-Cultural Belonging

Preferential Membership Policies in Europe

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Nationality, Citizenship and Ethno-Cultural Belonging

Preferential Membership Policies in Europe

About this book

This book challenges mainstream arguments about the de-ethnicization of citizenship in Europe, offering a critical discussion of normative justifications for ethno-cultural citizenship and an original elaboration of principles of membership suitable for contemporary liberal democratic states.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Nationality, Citizenship and Ethno-Cultural Belonging by C. Dumbrava in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Civil Rights in Law. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Citizenship Rules in Europe

1

Birthright Citizenship

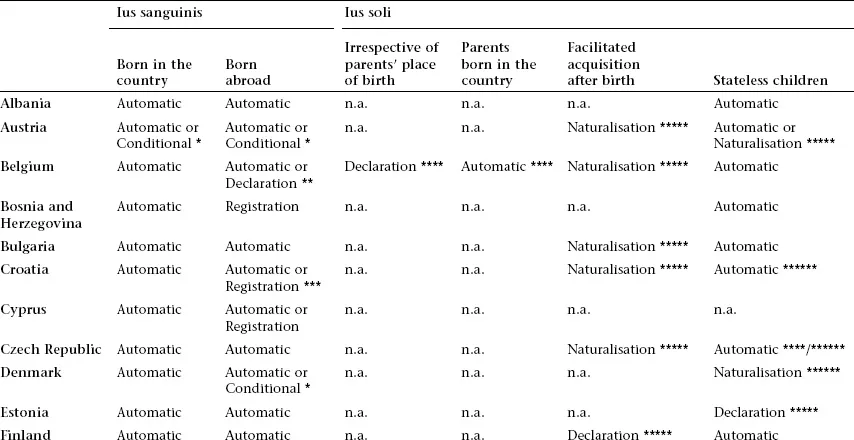

The overwhelming majority of people in the world acquire citizenship at birth through descent from citizens (ius sanguinis) or through birth in the country (ius soli). These two methods of acquisition of citizenship at birth (birthright citizenship) are not mutually exclusive because people can simultaneously acquire citizenship due to birth in the territory and also through descent from citizens. Despite the existence of different legal traditions in respect to rules of attribution of citizenship (Weil, 2001), nowadays an increasing number of countries use both methods of birthright citizenship. Recent research shows that countries have made comparable adjustments of citizenship laws, converging towards a model in which rules of ius soli and ius sanguinis are applied complementarily and conditionally (Hansen and Weil, 2001; Joppke, 2007a). In this chapter I first provide an overview of legal provisions on birthright citizenship in thirty-eight European countries and then discuss rules and aspects of birthright citizenship that appear to be inspired by ethno-cultural understandings of membership.

Ius sanguinis citizenship

The rule of ascribing citizenship at birth automatically to children of citizens is the most widespread rule of acquisition of citizenship in the contemporary world. Citizenship laws of all European countries included in the survey have ius sanguinis provisions. In fourteen countries ius sanguinis provisions apply unconditionally (see Table 1.1). In the remaining cases, ius sanguinis provisions apply with one or more qualifications. The major types of qualifications to ius sanguinis provisions concern: (a) the marital status of parents – whether the child is born within or out of wedlock, (b) the place of birth of the child – whether the child is born in the country or abroad, (c) the citizenship status of the parents – whether one or both parents are citizens, and (d) the method or circumstances in which the parents of the child acquired citizenship status – whether the parents acquired citizenship through descent or through other procedures.

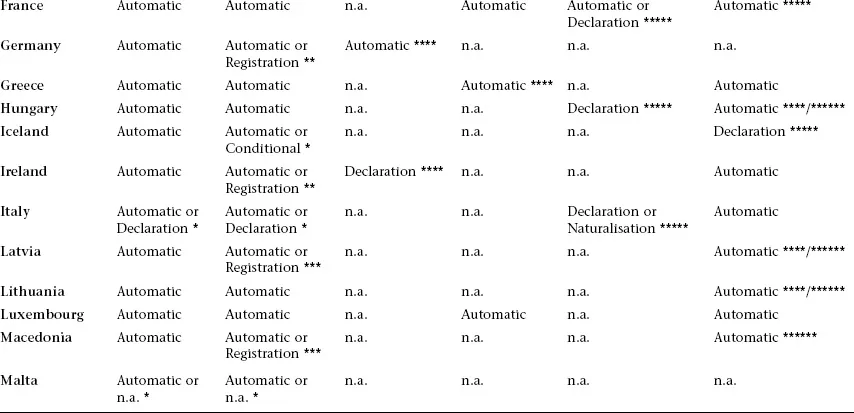

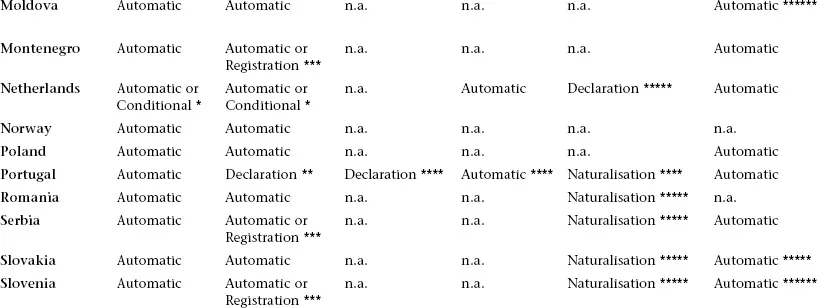

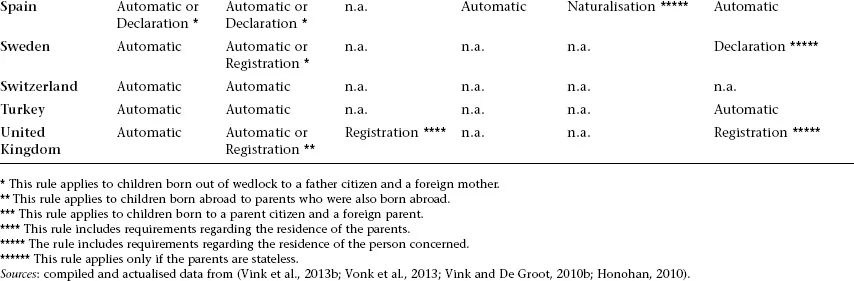

Table 1.1 Rules of birthright citizenship in Europe (2013)

There are a number of countries in the survey that make distinctions between children born within wedlock and children born out of wedlock when only the father is a citizen. Malta is the only country where children born out of wedlock to a foreign mother and a father citizen cannot acquire citizenship through ius sanguinis provisions. Whereas the majority of countries grant citizenship to children born out of wedlock to father citizens once paternity is established, the establishment of paternity has no effect on the citizenship status of these children in Austria and Denmark (Vonk et al., 2013: 52). In these two cases, children can acquire the citizenship of the father only if the parents marry. In Iceland and the Netherlands it is also possible for the father to recognise the child born out of wedlock, in which case, proof of a biological link with the child should be provided (in the Netherlands this rule applies if the child is older than seven). Cases where the legal recognition of the family relationship between parent and child has no effect on the citizenship status of the child, as well as cases where states impose substantive requirements for the application of ius sanguinis provisions, such as DNA evidence, are problematic and constitute contraventions to the provisions of the European Convention on Nationality (1997 Convention) (Vink and De Groot, 2010b: 14).1 In Denmark, Finland and Sweden, the distinction between children born within wedlock and children born out of wedlock is relevant for the application of ius sanguinis provisions only when the child is born abroad. In these cases, a child born out of wedlock to a father who is a citizen and a foreign mother can acquire citizenship if the father registers the child with the relevant public authority.

It is common that countries impose additional conditions for the acquisition of citizenship through ius sanguinis abroad. According to the citizenship laws of Croatia, Latvia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, and Slovenia, children born abroad to a parent citizen and to a parent non-citizen do not acquire citizenship automatically, but through special procedures of registration or declaration. Several countries impose additional conditions for the acquisition of citizenship via ius sanguinis abroad, but only starting with the second generation of citizens born abroad. In Portugal such restriction applies also to children born abroad to citizens who were born in the country but reside permanently abroad. In Belgium, Cyprus, Germany,2 Ireland, Malta, and the United Kingdom, children born abroad to citizens who were also born abroad can acquire citizenship only through registration or declaration. In the United Kingdom, the registration procedure includes a residential requirement. British citizens who were born abroad (citizens by descent) can register their children born abroad as British citizens only if they (parents) have resided for at least three years in the country.

Ius soli citizenship

According to the general principle of ius soli, citizenship is ascribed at birth to children who are born in the country. Rules of ius soli are less widespread than rules of ius sanguinis. Despite evidence that citizenship laws in Europe are increasingly converging towards a regime that combines elements of ius soli and ius sanguinis, the rule of ius soli “is by no means as firmly established in European citizenship regimes as it is often assumed” (Honohan, 2010: 23). First of all, no country in Europe provides for automatic and unconditional acquisition of citizenship by children of non-citizens born in the country (pure ius soli). Ireland was the last European country to maintain such a rule until 2004. Fifteen countries in the survey do not have any provisions regarding the acquisition of citizenship on grounds of birth in the country: Albania, Cyprus, Denmark, Estonia, Iceland, Latvia, Lithuania, Macedonia, Malta, Montenegro, Norway, Poland, Sweden, Switzerland, and Turkey (see Table 1.1). In those several countries where the principle of ius soli applies at birth, the acquisition of citizenship is conditioned by at least one of the following factors: (a) the place of birth of the parents, (b) the residential status or residential history of the parents, and (c) the occurrence of dual citizenship.

Children born in Belgium, Germany, Ireland, Portugal and the United Kingdom are entitled to ius soli citizenship in the respective countries regardless of the place of birth of their parents. Whereas in Germany and in the United Kingdom children born in the country receive citizenship automatically, in Belgium, Ireland, and Portugal they acquire ius soli citizenship only after their parents register or declare them as citizens. In all these countries, however, a child is entitled to citizenship only if her or his parents have been residents in the country for a minimum period of time before her or his birth. The minimum period of residence is three years in Ireland, five years in Portugal and the United Kingdom, eight years in Germany and ten years in Belgium. The case of Greece is noteworthy. According to the Greek citizenship law of 2010, children born in Greece to foreign parents can acquire Greek citizenship by way of declaration if their parents completed five years of residence in Greece as permanent residents. However, in February 2013 the Greek Council of the State ruled that ius soli provisions are unconstitutional because their automatic character does not allow for a “personalised judgment as far as the applicant’s ‘national consciousness’” (Christopoulos, 2013).

A more qualified version of ius soli requires that both the child and the parent(s) be born in the country (double ius soli). Provisions of double ius soli exist in: Belgium, France, Greece, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain. Whereas in France, Luxembourg and Spain this rule applies automatically and unconditionally, in the other countries ius soli provisions include residential requirements with regard to parents. In Portugal and the Netherlands parents must be residents in the country. In Greece they must enjoy the status of permanent residence, and in Belgium they must have been residents in the country for at least five years before the child’s birth. In the Netherlands a child qualifies for (double) ius soli citizenship if she or he is “born to a father or mother who has her or his main habitual residence in the Netherlands, the Netherlands Antilles or Aruba at the time of its birth, and if this father or mother was born to a father or mother habitually residing in one of these countries at the moment of the birth of her child, provided the child has also her or his main habitual residence in the Netherlands” (Vink and De Groot, 2010b: 26).

Apart from rules of ius soli that apply at the moment of birth, there are other provisions that take into account the fact of birth in the country. Eighteen countries in the survey have provisions of facilitated acquisition of citizenship after birth based on the fact that the person was born in the country (ius soli after birth). Whereas seven of these countries have also ius soli provisions at birth (Belgium, France, Greece, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain and the United Kingdom), in eleven cases these are the only type of ius soli provisions. These countries are: Austria, Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Finland, Hungary, Italy, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, and Slovenia. Provisions of facilitated acquisition of citizenship after birth always include, among others, requirements regarding residence in the country. The minimum period of residence required in these cases varies greatly among countries – between one year in Spain and eighteen years (since birth) in Italy and the Netherlands (Vink and De Groot, 2010b: 28–9). It is important to mention that in Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, and the United Kingdom provisions of ius soli after birth amount to an entitlement to citizenship.

The inclusive character of ius soli citizenship depends greatly on whether the country accepts dual citizenship at birth as the majority of children born in the country to foreign citizens are usually entitled to another citizenship through ius sanguinis. In Germany children who acquire German citizenship via ius soli provisions are obliged to renounce any other citizenship they possess between the ages of 18 and 23. The failure to renounce other citizenship causes the loss of German citizenship. Apart from Germany, ius soli provisions are incompatible with dual citizenship in Austria, Croatia, the Czech Republic and Spain. Whereas Germany and the Czech Republic allow for significant exceptions, such as in cases where it would be impossible or unreasonable to require the renunciation of other citizenship, Spain allows dual citizenship at birth only for citizens of certain countries3 (Honohan, 2010: 12).

Lastly, most citizenship laws contain special rules regarding the acquisition of citizenship at birth by children found in the country (foundlings) and by children who are stateless at birth. Except for Cyprus, all countries in the survey provide for the automatic acquisition of citizenship by children found in the territory. It should be noted that these provisions are based on the presumption that the parents of the child are citizens, in which case the child acquires citizenship through a presumption of ius sanguinis. Cyprus, Germany, Malta, Norway, Romania, and Switzerland do not have provisions regarding the acquisition of citizenship at birth by children who are otherwise stateless. In Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia and Lithuania the acquisition of citizenship by stateless children is conditioned on the residential status of parents, although this contravenes international norms4 (Vonk et al., 2013: 40, n.155). In Croatia, the Czech Republic, Hungary Latvia, Macedonia, Moldova, and Slovenia, children who are stateless at birth can acquire citizenship through a special procedure only if their parents are also stateless or without citizenship. This condition is problematic because statelessness can occur also when both parents are citizens, such as when neither of the parents can transmit their citizenship to the child (Vonk et al., 2013: 42). Lastly, in Belgium, Finland, France, Ireland, Portugal and Turkey children born stateless are not granted citizenship at birth if they are entitled to another citizenship.

Ethno-cultural rules of birthright citizenship

There is an ongoing debate about the normative meaning of birthright citizenship. According to one view, ius soli and ius sanguinis are indicative of different philosophies of membership. Rogers Brubaker (1992a: 187) argues that the two rules of birthright citizenship “express deeply rooted habits of national self-understanding.” Brubaker claims that the transmission of citizenship through bloodline indicates membership of an ethnic community, whereas the attribution of citizenship due to birth in the country denotes membership of a civic community. His dichotomist and culturalist view was justly criticised for its reductionism (Yack, 1996; Joppke, 2007a) and disproved by later reforms of citizenship laws in Europe. For example, in 1999 Germany – which epitomised the “ethnic” model of nationhood – adopted ius soli provisions, thus moving towards the “civic” end of Brubaker’s dichotomy (Weil, 2001).

In a historical perspective, there is no necessary link between legal rules of birthright citizenship and the civic or ethnic character of nations. In the common law tradition, the community of subjects was seen as a community of allegiance to the monarch and not as a territorial or ethnic community. As asserted by the early judgment in Calvin v. Smith (1608),5 the ascription of allegiance at birth was derived from the powers that the sovereign had over territory. In post-revolutionary France ius soli provisions were adopted to cope with problems generated by large-scale immigration. The major issue was that resident foreigners refused to acquire French citizenship in order to avoid military service. In this context, the adoption of automatic and compulsory ius soli served to impose on people born in France “l’egalité des devoirs” (Weil, 2009: 78). The adoption of ius soli in the United States was not related to immigration. It was constitutionalised through the 14th Amendment of 1868, in which the citizenship clause overruled the decision of U.S. Supreme Court in Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857),6 according to which Americans of African descent were not US citizens.

The adoption of ius sanguinis in modern Europe had less to do with the spread of nationalism than with the attempts by states to cope with modern challenges. The French Civil Code of 1803 provided that children born to French fathers, in France or abroad, acquired French citizenship at birth. Although this rule was derived from a Roman tradition, at that moment ius sanguinis expressed “a quintessentially modern understanding of membership” in which “the individual [was] no longer seen as the property of the feudal overlord, who had owned all the products of the soil, people included” (Joppke, 2005a: 53). Citizenship was thus conceived as an attribute of the person that could be transmitted to children like the fami...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part I Citizenship Rules in Europe

- Part II Ethno-Cultural Citizenship

- Part III Differentiated Membership

- Conclusion

- Notes

- References

- Index