- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Language for Specific Purposes

About this book

This book fully explicates current trends and best practices in LSP, surveying the field with critical insightful commentary and analyses. Covering course areas such as planning, implementation, assessment, pedagogy, classroom management, professional development and research, it is indispensable for teachers, researchers, students.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Concepts and Issues

1

Historical and Conceptual Overview of LSP

This chapter will:

- Outline the history of LSP

- Provide a conceptual overview of the field

- Discuss the interplay of theory-driven and data-driven approaches

- Discuss the interplay of theory and pedagogy in LSP

1.1 Introduction

When people speak of Language for Specific Purposes, they generally think about English for Specific Purposes, a subject that is usually broken down into English for Academic Purposes and English for Occupational, Vocational or Professional Purposes, as well as many other finer categories, such as English for business, English for engineers or even English for museum guides. But Language for Specific Purposes is a field that extends well beyond this to parallel domains in languages other than English, ranging for example, from Arabic for Religious Purposes and Portuguese for Academic Purposes to Chinese for Occupational Purposes. We wish to clearly acknowledge that much important LSP research and practice is taking place in languages other than English, although at this time studies in English dominate the published literature.

The study of the ways in which language can be used in specific contexts and to achieve specific ends is not new. Rhetoric and the power of rhetorical devices have been studied and taught at least since Classical Greek and Roman times in the West and for at least 24 centuries in the East (though the traditions of rhetoric teaching are quite different. See, for example, Gernet 1972/2002: 92–93).

The teaching of language for specific purposes burgeoned in the early decades of the renaissance in Italy: ‘alongside the ars notarie developed the ars dictaminis and the ars rhetorica, the medieval arts of writing and rhetoric, basic educational building-blocks’ (Denley 1988: 288). Leon Battista Alberti, for example, devised specialist terms, not without technical difficulty and some opposition, for architecture and related fields (Laurén 2002: 91).

The seventeenth century saw major developments in science and a concurrent development of a language of science. Gotti (2002: 65 et seq.) has pointed out the numerous complaints of seventeenth-century scientists such as Galileo, Bacon, Boyle and Digby about the inadequacy of everyday language and their recognition of ‘the need for a novel scientific language, quite different from ordinary speech’ (Gotti 2002: 65). Halliday also places the birth of scientific English in the seventeenth century, citing Newton’s Treatise on Opticks as a key text (Halliday 1993: 57–62).

The need for agreement on technical and commercial terminology as world trade expanded in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries resulted in a growth of lexicographical works aimed at fixing standard linguistic usage in much the same way as the Napoleonic metric system and the imperial system of weights and measures aimed to fix a universal standard of measurements. The need to control language diversity through definition of standards was also closely connected with the spread of European imperialism. ‘In 1862 one appeal for volunteer helpers in the national dictionary project refers explicitly to “the race of English words which is to form the dominant speech of the world”’ (Harris 1988: 18).

From the beginning of the twentieth century this need for language which avoids ambiguity became even more evident and for a long time now, trade groups such as the European Union and political groups such as the United Nations have spent significant time and resources on ensuring that negotiators, translators and interpreters agree on what their words mean. The political agenda, while perhaps not expressed in the same unapologetic words as in the nineteenth century, remains significant, and has stimulated considerable research and comment in recent years (Phillipson 1992; 2013, Tollefson 1995; 2011).

Much of the work on language for specific purposes in the twentieth century was, and still remains today, in the field of technical terminology. A number of schools of thought in the study of terminology as an academic field were established, perhaps most notably the Vienna School associated with the names of Wüster, Felber and others. Their work is undoubtedly important in the study of specific-purpose language and has been very influential in language planning and standardisation, particularly in international trade and political bodies. Some of their basic concepts, however, have been challenged. Their strict separation of meaning (‘concept’) and form (‘linguistic sign’), the insistence on the primacy of the concept, and the underlying assumption that concepts can be unambiguously defined have been strongly contested by terminology scholars (for example, in Temmerman 2000), by more socially-situated studies of language and by those who use newer technologies such as corpus analysis to reveal the dynamic nature of language in context (see, for example, Flowerdew 2012). The status of terminology as a separate field of study has also been challenged, for example by Sager (1990: 1): ‘Everything of importance that can be said about terminology is more appropriately said in the context of linguistics or information science or computational linguistics’.

Concept 1.1 The five principles of the Vienna school for terminology

- A definition of the concept precedes the allocation of a term

- Concepts can be clearly defined in relation to other concepts

- Concept definition uses specific definition-types: intensional (i.e. a listing of characteristics differentiating the concept from similar concepts), extensional (a listing of all the objects belonging to the concept) and part-whole (a definition relating the part to a superordinate concept)

- There is a one-to-one correspondence between term and concept (the principle of univocity)

- Terminology studies are synchronic – terms are assigned permanently and there is no room for language development

(Felber 1981)

Recent works on standards have questioned whether the idea of standardisation can be maintained. In their edited volume on Standard English: The widening debate, Bex and Watts (1999) note that ‘notions of “Standard English” vary from country to country, and not merely in the ways in which such a variety is described but also in the prestige in which it is held and the functions it has developed to perform’ (5).

It is a widespread idea that what is specific about specific language is the terminology used: that technical language uses technical words, scientific language uses scientific words, the language of particle physics use particle physics words, and so on. This is the lay, common-sense view, and it is not surprising that novice teachers faced with the task of devising a highly specific course (on, say, Russian for marine engineers), sometimes reach for the lexicon and construct their course as a series of vocabulary-building exercises. In fact, some published special-purpose textbooks do very little more.

It will be evident, however, that successful communication involves far more than establishing the meaning of individual lexical items and phrases. How much more will become apparent in the pages of this book, which is concerned with what is encompassed in the field of language for specific purposes (LSP) and the ways in which its intellectual development and practical applications have interacted with each other and can proceed into the future.

1.2 Theory, practice and research in LSP

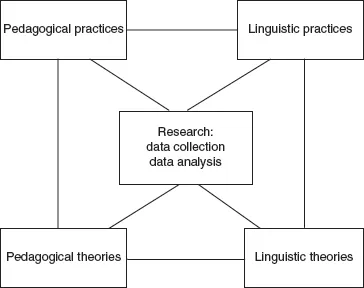

Varantola (1986) distinguishes between LSP as a description of a language variety and LSP as a curriculum/pedagogic variety. At first sight, this distinction seems similar to that between theory and practice, but it is not completely congruent with that distinction, as the existence of linguistic theories and pedagogical practices can be paralleled by pedagogical theories and linguistic descriptive practices (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Theory, data and practice

Nonetheless, the parallels between the linguistics/pedagogical divide on the one hand and the theory/practice divide on the other are often assumed and underlie much of the debate in LSP as well as in applied linguistics more generally.

Some researchers in the field have little or no interest in teaching applications, seeing these as belonging to a separate field (of ‘didactics’, ‘pedagogy’, ‘andragogy’ or ‘education’), while their own work is a sub-field of linguistics. Some practitioners see research as having no immediate relevance to their teaching classrooms, where issues of what motivates learners and what ‘works’ in class may be based on a pragmatic mix of activities driven by experience rather than theory. The field of LSP has at different times been predominantly theory-driven and at other times predominantly practice-driven.

A further distinction is made by de Beaugrande (1989: 15) between ‘theory’ and ‘data’. De Beaugrande suggests that linguistics in general has been sometimes data-driven, sometimes theory-driven.

Quote 1.1 de Beaugrande on theory and data

Linguistics has long vacillated between models of theory and models of data. In general, ‘structural’ linguistics gathered unprecedented quantities of data, but was rather sparse in its theories, whereas ‘generative’ linguistics created many models of theory, but was quite noncommittal about obtaining data.

(de Beaugrande 1989: 15)

An early attack on the function-based ESP textbooks of the 1970s also referred to these distinctions, suggesting that the then newly-emerging ESP textbook series such as Focus (Allen and Widdowson 1974 and later) and Nucleus (Bates and Dudley-Evans 1976 and later) were driven by linguistic theory without data and by pedagogical theory with little attention to pedagogical and curriculum development practice.

Quote 1.2 Ewer and Boys on state of EST textbooks in 1970s

Although the [10 EST] textbooks examined claimed unreservedly to teach the language of science and technology, there is little evidence that their authors have made the necessary efforts to find out what this language consists of in the first place, and the lack of agreement between textbooks as regards their valid teaching contents only emphasises the haphazard nature of the linguistic criteria applied. As a result, the teaching points selected in each case cover only a small proportion of the significant features of scientific discourse; at the same time there are serious inadequacies in the ways in which these points are explained, exemplified and exercised, as well as a general lack of additional help for both students and teachers.

(Ewer and Boys 1981: 95)

By contrast, Dudley-Evans (1997: 59) denies that LSP has an established theory and suggests that training in LSP should focus on course design procedures rather than theory.

Quote 1.3 Dudley-Evans on LSP theory

… there is not an established theory for ESP in the same way as there is for, say, Communicative Language Teaching and Second Language Acquisition. … The emphasis on ESP/LSP courses has been on the procedures followed in setting up courses, carrying out text analysis and writing and evaluating teaching materials. … LSP training needs to concentrate on this ‘set of procedures’.

(Dudley-Evans 1997: 59)

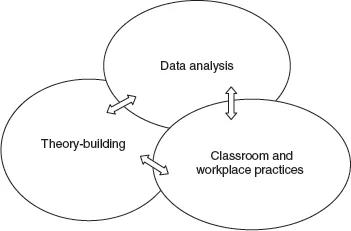

We would like to suggest that the connection between teaching, research and theory is, and should be, much more complex. While there are many different research perspectives on the field of language for specific purposes, and we will outline many of these in this book, our interest is in the multi-directional flow between research, teaching and the theories that inform and are informed by practice and analysis (see Figure 1.2). We suggest also that theory-building, data analysis and workplace/classroom practice, while interdependent, have at different times each taken a dominant role in the development of the field.

In the field of language for specific purposes, where the ‘language’ component is closely linked to the ‘special purpose’, there are at least two interlocking systems at play. One Venn diagram like Figure 1.2 might link our own professional practice as linguists with linguistic theory and linguistic data, while a parallel set of components would represent the professional practices, the data and the theories of the targeted special purpose. The complexities of the resulting connections might lead us to question whether there can ever be a single set of generally accepted principles for the field of LSP.

Figure 1.2 The relationship between theory, data and professional practice

We see LSP as necessarily interdisciplinary, drawing on insights and practices from a wide variety of sources. In particular, LSP is not a mere sub-field of foreign language teaching, though it looks to foreign language teaching as one of its sources. We see LSP as interdisciplinary not merely because it deals with the language practices of other fields, but as interdisciplinary even within linguistics and other academic disciplines. LSP gains insights from, and contributes to, fields such as pragmatics, discourse analysis, motivation theory, philosophy of science, genre and register theory, sociolinguistics, cognitive linguistics, technical and professional communication, literacy, terminology studies, intercultural communication, epistemology, management communication, computational linguistics, lexicography, language planning, semantics, text linguistics, stylistics, language acquisition, translation and interpreting and many others.

Despite its overlap with so many other disparate fields, and its inherent overlap with special-purpose fields, it is worthwhile to try to define what it is about LSP that can give it an identity as a professional field. What is the agenda for LSP? What are the areas which practitioners, theorists and researchers can agree are worthy of our attention? For us, the LSP agenda is to characterise the ways in which language is used in specific contexts by specific groups for specific purposes, to explore the extent to which language use in such contexts is stable, to examine the role of language in establishing, maintaining and developing group values and self-identification, and to identify and evaluate the means by which people can become proficient in using language in specific contexts for their own specific purposes, and can graduate to membership of their target group or groups.

1.2.1 A theory-driven stage: communicative language teaching and notional syllabuses

There were many examples of specialised goal-oriented courses before the blossoming of LSP, and in particular ESP, as a self-identified field in the 1970s. Not all of these were as focused on terminology and word-frequency as is sometimes thought. An interesting example is a 1932 book designed to teach ‘medical Arabic’ for medical workers in Syria and Palestine whose first language was Hebrew, French or English. The book consisted of questions and answers, with translations, of the kind to be expected in doctor-patient interaction, and of ‘conversations’ in colloquial Arabic based on medical topics as they might be explained to a patient (Haddad and Wahba 1932, described in Rosenhouse 1989). Another example is the introduction of German as a Foreign Language into the curriculum of a Medical School founded by a German doctor in 1907 in Shanghai, China (Fluck and Yong 1989).

Although LSP was clearly not ‘inv...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- General Editors’ Preface

- Acknowledgements

- About the Authors

- Introduction

- Part I Concepts and Issues

- Part II LSP in the Classroom

- Part III Conducting Applied Research in LSP

- Part IV Resources

- References

- Author Index

- Subject Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Language for Specific Purposes by Sandra Gollin-Kies,David R. Hall,Stephen H. Moore in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Comparative Education. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.