- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Considered a notorious subset of horror in the 1970s and 1980s, there has been a massive revitalization and diversification of rape-revenge in recent years. This book analyzes the politics, ethics, and affects at play in the filmic construction of rape and its responses.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Revisionist Rape-Revenge by Claire Henry in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Remaking Rape-Revenge: The Last House on the Left (1972/2009) and I Spit on Your Grave (1978/2010)

In order to illustrate the shifts between the classic and revisionist cycles of the genre, this chapter compares two canonical rape-revenge films with their recent remakes: The Last House on the Left (Wes Craven, 1972/Dennis Iliadis, 2009) and I Spit on Your Grave (Meir Zarchi, 1978/Steven R. Monroe, 2010).1 As canonical texts with both contemporary remakes and their own ongoing cult status, these films attest to the enduring relevance and popularity of the rape-revenge genre.2 This chapter identifies key generic elements of rape-revenge instituted by these texts and uses the comparison between original and remake as a barometer of the genre’s continuities and changes. Later chapters delve into the diversity and the complexities of the revisionist genre—its more marginal, hybrid, and transnational manifestations—but I begin in this first chapter with the proposition that these films are the prototypical, or definitional, texts for the (Western) rape-revenge genre and, as such, can be used to elucidate the central features and issues of the genre.

Remaking crystallizes the process of genre repetition, so remakes are particularly useful as objects of study in the analysis of a genre. Most remakes are genre films, and they simultaneously revise the codes and conventions of their source films and their genre. Following Constantine Verevis’ approach, remaking can be understood as part of a wider intertextuality (2006, 59), and his points about the original The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (Tobe Hooper, 1974) are perhaps even truer of I Spit and Last House:

Viewers who fail to recognise, or know little about, an original text may understand a new version (a remake) through its reinscription of generic elements, taking the genre as a whole (rather than a particular example of it) as the film’s intertextual base. For instance, the producers of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre [Marcus Nispel, 2003] say that the idea of remaking the seminal slasher movie was in part motivated by research showing that 90 per cent of the film’s anticipated core audience (eighteen to twenty-four year old males) knew the title of Tobe Hooper’s original but had never seen it. (Verevis 2006, 146)

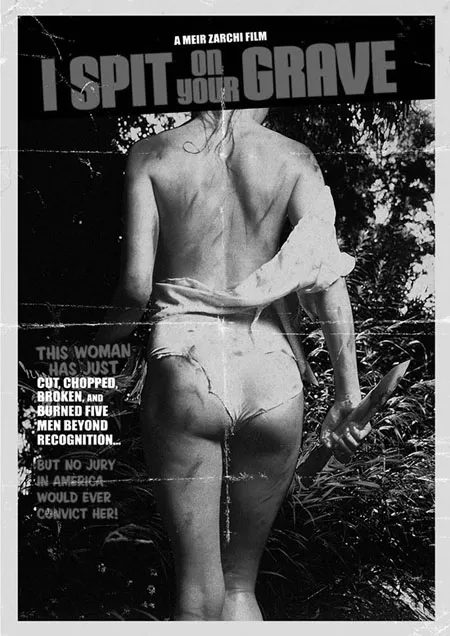

Like Texas Chainsaw 1974, Last House 1972 and I Spit 1978 are exploitation or “video nasty” titles that are mentioned for their notoriety more often than they are actually seen, particularly by younger audiences. This suggests that fidelity is not so important for the target audience; what the remake is re-creating is the original’s “narrative image” as opposed to its content (although these remakes do also rather faithfully replicate the narratives). Steve Neale argues that genre is “an important ingredient” in a film’s “narrative image,” which is an idea of a film that is widely circulated and promoted in both institutionalized and unofficial public discourse (2000, 39). For many, the “narrative image” of I Spit 1978 is the scantily clad, blood-soaked female avenger made iconic through the poster (which is replicated on the I Spit 2010 poster, but appears in neither film). This can be considered rape-revenge’s presold concept, or the reduction of the genre down to a saleable image. I Spit 2010 does not require detailed familiarity with the original source text—indeed, the spectator may only have this narrative image as a reference point—rather, it banks on the cultural memory and reputation of the original for its appeal.3

Are these remakes then—along with other contemporary horror remakes such as A Nightmare on Elm Street (Samuel Bayer, 2010) and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (Marcus Nispel, 2003)—just cynical “rebranding exercises” (Mark Kermode, quoted in Verevis 2006, 4), simply remaking a successful narrative image and cashing in on the notoriety of the originals? Commercially, there is undoubtedly a degree of this, but I will suggest that there is more to these remakes, that they involve the rearticulation of a story that needs to be retold. Leo Braudy’s view of remakes supports this:

In even the most debased version, it [a remake] is a meditation on the continuing historical relevance (economic, cultural, psychological) of a particular narrative. A remake is thus always concerned with what its makers and (they hope) its audiences consider to be unfinished cultural business, unrefinable and perhaps finally unassimilable material that remains part of the cultural dialogue—not until it is finally given definitive form, but until it is no longer compelling or interesting. (1998, 331)

Figure 1.1 I Spit on Your Grave (Meir Zarchi, 1978) film poster. Courtesy of Barquel Creations, Inc.

If it is true that, as Michael Brashinsky suggests, “When the myth of a genre (the frontier naïveté of the western, or the apocalyptic dread of the disaster film) does not match the myth of the time, the genre fades away” (1998, 167), then these contemporary remakes indicate an ongoing relevance of the rape-revenge genre’s underlying myths. Even if the “copy” is deemed inferior to the “original” (as is often the case), remakes are a rich site for exploring the genre, the epoch, and these underlying myths or “unfinished cultural business.” So this chapter asks: beyond obvious commercial reasons, why are these films being remade, and why now? Which elements of the genre are specific to the time of their production, and which are the enduring elements? How are the remakes in dialogue with their originals, with their political contexts (including war and feminism), and with their genres? In a post-9/11 American context, rape-revenge remakes have been adopted as a format for working through ideological issues around revenge, retribution, and family values. The case studies in this chapter demonstrate how the format can be shaped to align with an American political neoconservative trend toward promoting family values and clear ideological divisions between “us” and “them.” This ideological timeliness converges with rape-revenge’s generic and aesthetic currency in contemporary cinema to help explain the revival of the genre’s popularity in American cinema.

Between the production of these 1970s classic rape-revenge films and their remakes over 30 years later, rape-revenge had been “remade” many times, reasserting some conventions, reshaping others. The following comparisons of these two more direct, explicit remakings will elucidate the key changes in this period and identify the features that continue to be core. It is important to locate the changes in both sociopolitical and genre contexts. The originals can be located in terms of 1970s exploitation cinema and “video nasties,” while the remakes have strong ties to the torture porn genre, a genre that emerged in the early twenty-first century. How do these genres inflect the meanings of the films, in particular their representations of violence? The revival of rape-revenge in contemporary Hollywood horror might be attributable to the fact that the rape-revenge narrative lends itself well to being overlaid with torture porn gore, in that rape is a form of torture and its eye-for-an-eye vengeance involves other spectacles of violence or body horror. Deeper convergences with this genre can be seen through Adam Lowenstein’s reconceptualization of torture porn as “spectacle horror,” defined as “the staging of spectacularly explicit horror for purposes of audience admiration, provocation, and sensory adventure as much as shock or terror, but without necessarily breaking ties with narrative development or historical allegory” (2011, 42). In a similar way to how torture porn theorists such as Lowenstein (2005; 2011) and Jason Middleton (2010) outline their respective genre’s capacity and limitations in working through national/historical tensions and traumas allegorically, this chapter examines how contemporary rape-revenge feeds into the working through of American post-9/11 ideological and ethical questions around torture, revenge, and witnessing violence in the “war on terror.”

The originals and remakes confront and challenge the spectator in slightly different ways, and in order to understand the pleasures and displeasures offered by the genre, this chapter will closely examine their violent spectacles in both rape and revenge scenes. Analogous to Lowenstein’s finding that attractions tend to trump identification in the spectatorship mode of “spectacle horror” (2011, 43–44), we find that in these remakes, spectatorial expectation revolves not so much around the question of how far the victim-avenger will go in taking revenge, but around the more genre-savvy and spectacle-hungry question of how far the filmmakers will go in depicting it. If identification or empathy with the rape victim is not (or no longer) key, what implications does this have for the politics of representing rape? And why is it that we still want to see revenge enacted? At the level of cultural allegory, the remakes’ spectacles of violent vengeance seem recuperative as opposed to critical—celebrating rather than condemning violence, and reassuring the audience rather than implicating them in ethical questions raised by American actions in the “war on terror.” These factors related to the particular cultural/political moment are shored up at the level of genre—the imperative for revenge and the spectacle of violence are strong generic demands, which can undermine sociopolitical critique around issues of sexual violence and (allegorically) around issues of retribution and torture in the “war on terror.”

The Last House on the Left

The taglines for Last House 1972 and Last House 2009 encapsulate the films’ key sites of difference: their relationships to violence and their relationships to their respective cultural contexts. The famous and frequently imitated tagline for Last House 1972—“To avoid fainting, keep repeating, ‘It’s only a movie . . . It’s only a movie . . .’ ”—flags a disparity between the films’ uses of violence and horror: where the original teased potential audiences with the realism of the violence, challenging them to withstand a viewing and to confront its allegorical engagement with historical trauma, the remake makes blatantly obvious that the violence is that of “only a movie” by presenting pleasurable spectacles of cartoonish and gory violence (which contrasts with the news photography aesthetic of Last House 1972). Last House 1972 also begins with a “true story” epigraph, unimaginable in a remake: “The events you are about to witness are true. Names and locations have been changed to protect those individuals still living.”4 The advertising and the original’s epigraph set up different modes of viewer reception between the two films.From the outset, Last House 1972 signals to the audience that they should expect a challenge and confrontation, and while the remake similarly promises to push viewers’ boundaries, this time it is in terms of the pleasures of a Hollywood patriarchal revenge fantasy and the spectacle of screen violence, as captured in the tagline: “If bad people hurt someone you love, how far would you go to hurt them back?” While the remake is on the surface a faithful one, a closer look reveals distinct ideological agendas between the two films. The contrasts point to the adaptability of the genre, suggesting one reason for its endurance into the twenty-first century.

Last House 1972 is a story in two parts, both with climactic, brutal scenes of violence. In the first half, Mari Collingwood (Sandra Cassell) heads to a concert in the city with her friend, Phyllis Stone (Lucy Grantham), on her seventeenth birthday. Seeking to buy some marijuana in the city, the girls meet Junior, who takes them into an apartment where the Stillo gang trap them and begin their torment. The four gang members—Krug (David A. Hess), Weasel (Fred Lincoln), Sadie (Jeramie Rain), and Junior (Marc Sheffler)—kidnap the girls, then when their car breaks down by the woods near Mari’s home, they continue to intimidate, humiliate, and rape Phyllis and Mari, and finally murder them. In the second half of the film, the gang arrives at the Collingwoods’ house and asks for help, as their car has broken down. Dr. and Mrs. Collingwood (Gaylord St. James and Cynthia Carr) provide them with a meal and beds for the night but later discover that the gang has murdered their daughter and then proceed to take their violent revenge. Last House 2009 replicates this plot, with a few minor but illuminating changes. Perhaps the most significant of these is that both Mari and Junior (renamed Justin) survive. While Mari is too badly injured to play any role in the revenge and is seen very little in the second half, both her and Justin’s survival (and his switch to the good guys’ side) gives the film a more uplifting and redemptive ending. While Last House 1972 ends on a bleak and bloody freeze-frame of Mari’s parents after they have killed the gang members, Last House 2009 ends with an image of the family—Mom (Monica Potter), Dad (Tony Goldwyn), Mari (Sara Paxton), and their new surrogate son Justin (Spencer Treat Clark)—restored and heading to safety on their boat over the lake.

Roger Ebert’s review of Last House 1972 in Film Comment (July–August 1978) was prophetic: “It’s a neglected American horror exploitation masterpiece on a par with Night of the Living Dead. As a plastic Hollywood movie, the remake would almost certainly have failed. But its very artlessness, its blunt force, makes it work” (quoted in Wood 2003b, 108). In certain respects, the 2009 remake is this plastic Hollywood movie. The remake has a blandness and an insularity that disappoints against the impact of the original. The raw power of the violence, the film’s bleak condemnation of violence and implication of the spectator, the complex empathies it evokes, and its engagement with its cultural context (particularly the counterculture and opposition to the Vietnam War) are what distinguished the original film and established its ongoing cult status. The remake tends to lack these qualities with its one-dimensional characters, its bland po-faced cast, its disturbingly unaffecting violence, its lack of sociopolitical critique (regarding violence, class, the family, or the law), its emphasis on family values, and its neat adherence to Hollywood genre conventions. The contrast might be summed up with a significant icon change in the remake—Mari wears a necklace from her dead brother Ben (inscribed “Always Go For Gold Your Big Bro BEN”) rather than the peace symbol necklace she wears in the original. This necklace represents the shift from Mari’s construction as a sexually curious teenager in the original to a mourning sister in the remake, and it also serves as a marker of the remake’s broader depoliticization and return to family values. These differences are in line with Adam Lowenstein’s findings about the renouncing of politics with...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Reapproaching Rape-Revenge

- 1 Remaking Rape-Revenge: The Last House on the Left (1972/2009) and I Spit on Your Grave (1978/2010)

- 2 The Postfeminist Trap of Vagina Dentata for the American Teen Castratrice

- 3 Rape, Racism, and Descent into the Ethical Quagmire of Revenge

- 4 The Shame of Male Acolytes: Negotiating Gender and Sexuality Through Rape-Revenge

- 5 Collective Revenge: Challenging the Individualist Victim-Avenger in Death Proof, Sleepers, and Mystic River

- Conclusion: Challenging the Boundaries of Cinema's Rape-Revenge Genre in Katalin Varga and Twilight Portrait

- Notes

- Works Cited

- Filmography

- Index