eBook - ePub

Policy Signals and Market Responses

A 50 Year History of Zambia's Relationship with Foreign Capital

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Policy Signals and Market Responses

A 50 Year History of Zambia's Relationship with Foreign Capital

About this book

The study presents archival evidence to show how President Kaunda raised political and economic exclusivity in Zambia in the early years of Zambia's independence, and how this retarded capital investment. Despite formal reforms and a new government, this institutional mechanism still dominates and constrains Zambia's political economy today.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Policy Signals and Market Responses by Stuart John Barton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Finance. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction and Background

Introduction

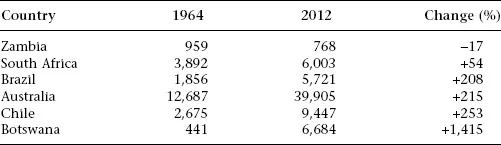

When looking back over 50 years of Zambian independence, it is disappointing to note how unsuccessfully its leaders have converted the country’s abundant natural resources and peaceful political history into economic growth. In fact, by some measures, Zambians are worse off today than they were at Independence in 1964. According to the World Bank, for example, real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per Zambian has shrunk by almost a fifth since 1964, a poor result considering the impressive growth enjoyed by so many other resource-rich economies (Table 1.1).1

On 24 October 1964, the Republic of Zambia emerged peacefully from the British protectorate of Northern Rhodesia as a multi-party democracy, endowed with one of the world’s largest deposits of copper and cobalt, a growing national economy, and a healthy reserve of foreign currency.2 But despite this relatively fortuitous start, in less than ten years, its economy was near collapse, and the nationalist Government of the Republic of Zambia (GRZ) was relying increasingly on foreign borrowing.3 By the mid-1980s, Zambia had not only become one of the poorest countries on earth but also amassed one of the largest public debts in history, equal to almost four times its entire GDP.4

This rather dismal economic performance has affected all aspects of Zambian life, and over time Zambians have fallen well behind many of their peers in terms of life expectancy, literacy, and education. In 2013, the United Nations Development Programme ranked Zambia just 163rd in terms of Human Development, only marginally ahead of Djibouti, Benin, and Rwanda.5

Table 1.1 Comparative GDP per capita since 1964 in constant 2005 USDs

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators.

Existing explanations for this rather poor performance have grown from economic and political analyses focused on the effects of four constraints: the persistent legacy of colonialism in the region, the country’s deep dependency on copper exports, its landlocked geography, and the economic impact of domestic policy. For example, Richard Hall has highlighted the economic strain on the GRZ of dealing with its ideologically opposed ‘white’ neighbours, and Alastair Fraser has emphasised the impact of volatile copper prices on the government’s planned economy.6 David Bloom et al. have all looked to Zambia’s geography for explanation, while Benno Ndulu has considered how these otherwise exogenous constraints may have been exacerbated by domestic policy.7

Historians have added to these analyses by showing how seemingly independent factors may in fact have been linked, and how a more nuanced, path dependent explanation for Zambia’s slow growth may prove more instructive.8 Gareth Austin, for example, has emphasised the importance of considering causative relationships arising from particular historical paths, and his approach may help explain some of the GRZ’s policy decisions as an inevitable reaction to Zambia’s unique colonial and pre-colonial history.9 Daron Acemoglu et al. have developed this causative and path dependent approach by building on Douglass North’s field of New Institutional Economics (NIE) to argue that economic outcomes evident in countries today may be explained by earlier institutional formation.10 This too may help explain Zambia’s reversal.

Testing this approach, Sophia and Stan du Plessis have confirmed a statistical link between Zambia’s institutional history and its economic growth, and to date their work stands out as one of the best applications of NIE theory to an African economy.11 However, by relying on a largely econometric methodology, their study demonstrates the existence of a relationship between one measure of institutional quality (contract intensive money) and economic growth but does not describe a mechanism through which the relationship may have manifested itself. In fact, no published account of Zambia’s history has yet provided a fine-grained narrative of how its institutional history has affected its economic growth.

This gap may be due to the availability of data. Quantitative sources from the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), for instance, are considerably more accessible than the more qualitative historical data held in archives in Lusaka, and the cost of data collection may have resulted in this quantitative focus. This book attempts to fill that gap by presenting previously unpublished archival evidence to explain Zambia’s disappointing trajectory through a mechanism that links its institutional history with its economic growth.

The book aims to answer the question: How has institutional quality affected Zambia’s economic growth? It charts Zambia’s 50-year relationship with foreign capital by exploring the link between the institutional change brought about by successive Zambian governments, the signals these institutional changes sent to providers of capital (both investors and lenders), and their related responses. By doing so the book hopes to expand our understanding of the relationship between institutional quality and economic growth by presenting one mechanism through which this frequently cited relationship may have manifested itself in Zambia. The book argues that growing institutional exclusivity in the 1960s and 1970s reduced constraint on Zambia’s Executive branch of government, resulting in increased policy uncertainty, which in turn retarded capital investment and ultimately restrained economic growth.

To make this argument, the book builds on three sub-arguments presented in chronological order in Chapters Three through Five, namely that: (1) a growing political exclusivity between 1964 and 1970 modified Zambians’ perceptions and expectations of their President and the State, and that this both allowed and encouraged President Kenneth Kaunda to make a series of sub-optimal economic policy decisions; (2) a growing economic exclusivity, brought about by political exclusivity and popular pressure, narrowed the field of economic interests in Zambia and most importantly excluded some foreign investors; and (3) the IMF’s balance-of-payments support between 1976 and 1983 lifted the foreign exchange constraint on the GRZ, a constraint that would have otherwise challenged exclusive and non-economic practices through the discipline imposed by market forces.

The book proceeds to apply this institutional perspective to interpret Zambia’s more recent history in Chapters Six through Eight, to help understand how formal reform after 1991 catalysed economic growth, highlighting that: (1) while formal reform was required, it was not sufficient to bring about the institutional reform needed to overcome established informal and exclusive practices; (2) the persistence of these exclusive practices, coupled with the GRZ’s history of policy volatility, required considerable concessions to attract foreign investment and privatise state-owned mines in 2000; and (3) Zambia’s Multi-Facility Economic Zone (MFEZ) initiative was a successful attempt by the GRZ in 2007 to mitigate this institutional history and engineer a popular ‘short-term win’ as well as to nucleate broader reform elsewhere.

As a whole, the book argues that seeking to explain Zambia’s economic history solely by interpreting the impact of seemingly independent events (such as volatile copper prices and the GRZ’s implementation of specific policies) oversimplifies the causes of Zambia’s slow growth by overlooking the institutional environment which framed the government’s actions and reactions. Specifically, it shows how promises made by President Kaunda and his United National Independence Party (UNIP) before Independence in 1964 precipitated the inevitable unravelling of institutional constraint in the 1960s and 1970s, and subsequently facilitated path-altering policies that can be demonstrated to have impeded investment and economic growth in the 1970s and triggered an addiction to debt in the 1980s, before resisting reform in the 1990s and leading to the highly concessionary privatisation of the country’s largest copper mines in 2000.

Methodology and sources

The book analyses unpublished archival evidence collected in Zambia, South Africa, and the United Kingdom, as well as newspaper reports, and elite interviews to engage with and build on previous academic findings and arguments. Wherever possible, multiple sources have been sought to provide triangulation and perspective on important events.

Before approaching primary sources, a comprehensive review of previous literature discussing Zambia’s economic history was conducted, the results of which are presented in Chapter Two. This literature can be divided by approach into three distinct time periods. Early analysis (1960–1980) was dominated by highly quantitative economic approaches, extending economic methods applied in Europe and the United States to newly independent Zambia. The dominance of this approach in Zambia’s early years may be the result of the quantity and quality of data available at the time but was also a result of a perhaps naïve belief in the economics profession, where models and methods designed in more developed economies would be directly applicable to independent Zambia. Analyses after 1980 recognised this problem and began to acknowledge the importance of policy-making to economic outcomes, focusing on this interaction to expand on earlier more quantitative analyses. By the mid-1990s, following the disappointing result of synchronised political and economic reform in Zambia, analysis began to focus on the formal institutional underpinnings of Zambian social, political, and economic activity, including the importance of institutions in stabilising policy. This book incorporates findings from all three of these periods and approaches to build on the emerging institutional analysis.

Following the literature review, a comprehensive search of the press was conducted, both electronically where available and in original paper format in Zambia. Three newspapers were found to be particularly useful: The Times of Zambia, The Guardian, and The Wall Street Journal. These sources were chosen ahead of others for three reasons: firstly, their broad distribution – The Times of Zambia was until the 1990s Zambia’s most read newspaper, the Guardian one of the United Kingdom’s leading broadsheets. Secondly, their coverage of the Zambian economy – The Guardian provided consistent coverage of Zambian politics as well as the fortunes of the country’s largest investor Anglo American Corporation (Anglo), while The Wall Street Journal offered a financial perspective on American interests in Zambia through coverage of its second largest investor American Metal Climax Inc. (AMAX). Thirdly, the accessibility and searchability of the sources – several complete copies of The Times of Zambia exist and are readily available in Zambia (Lusaka and Kitwe), while complete electronic copies of The Guardian and The Wall Street Journal covering the period 1964–2014 exist and are searchable through electronic data providers. Other less complete searches were conducted of the Zambian Post, The Financial Times, The Times, Bloomberg News, Chinese Xinhua News online as well as numerous trade newspapers.

Once these reviews were complete, the backbone of the research began. Archival searches were conducted across three visits to Zambia between 2010 and 2013. All the Zambian collections accessed were housed either in the National Archives of Zambia, the UNIP archive, or the Parliamentary archive in Lusaka. Photographic copies were taken of all documents viewed in the UNIP archive and some, where allowed, in the National and Parliamentary archives. While the three archives were readily accessible, the indexing and condition varied greatly and in some cases proved incomplete. In general, the National Archive provided the best conditions for research, the Parliamentary archive collection was highly incomplete, and the UNIP archive was only partially indexed. Of the collections accessed, few have been published and many have either never been analysed or the results never published. In most cases, the archival documents used in this book have not been referenced by historians before.

The National Archive in Lusaka holds three collections relevant to this book: the Industrial Development Corporation of Zambia (INDECO) collection, the Zambia Industrial and Mining Corporation (ZIMCO) collection, and The Sardanis Papers. The INDECO collection contains internal and external correspondence between INDECO officials, customers, suppliers, members of the civil service, members of Parliament, and President Kaunda himself. The collection also includes minutes of meetings, including those discussing the nationalisation of Zambia’s mines. While highly informative, this collection is small and gives the impression of being quite selective. The ZIMCO collection is far larger and contains similar correspondence and minutes as well as financial reports and audits for the ZIMCO conglomerate after its formation in 1982. However, this archive proved incomplete, with an entire box of documents from August 1969 entitled ‘INDECO mines take-over’ (referenced in the archive as ZIMCO 1/1/14) missing from the collection. The Sardanis Papers, again a small collection, comprise mainly personal correspondence between Andrew Sardanis, CEO of INDECO 1965–1970, and senior government officials, including Kaunda. What is notable about this collection is that, unlike the other two, it is made up mainly of copied documents deposited in the archive by Sardanis himself and therefore may also be selective.

The UNIP archive in Lusaka is a far less formal collection of documents. The collection is stored in an airy pre-fabricated building behind the now near-defun...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations

- 1 Introduction and Background

- 2 What the Literature Already Tells Us

- 3 Control: Responsibility and Risk (1964–1970)

- 4 Exclusion: Centralisation and Contraction (1970–1974)

- 5 Crisis: Decline and Denial (1975–1981)

- 6 Conditionality: Inertia and Adjustment (1981–1991)

- 7 Reform: Building Trust and Raising Capital (1991–2005)

- 8 Inclusion: Stability and Growth (2005–2014)

- 9 Zambia’s 50-Year Relationship with Foreign Capital

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index