eBook - ePub

Japan’s Foreign Aid Policy in Africa

Evaluating the TICAD Process

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Japan’s Foreign Aid Policy in Africa

Evaluating the TICAD Process

About this book

Japan's Foreign Aid Policy in Africa seeks to evaluate TICAD's intellectual contribution to and its development practices regarding Africa over the past 20 years. A central conclusion is that, while TICAD bureaucrats lacked agency to support Japanese companies in Africa, the model of emerging powers partnerships has expanded in Africa.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Japan’s Foreign Aid Policy in Africa by Kenneth A. Loparo,Pedro Amakasu Raposo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & African Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Evolution of TICAD over the Last 20 Years

Abstract: This opening chapter reviews Japan’s foreign aid policy regarding Africa and the changes leading to Tokyo International Conference on African Development (TICAD). It traces the historical evolution of the five TICADs, in relation to each conference’s guidelines, implementing policies and action plans from 1993 to 2013. It concludes that TICAD lead the way for Asian emerging powers to establish their own development partnerships. This is relevant to understanding the context of their foreign aid policies in the last chapter.

Raposo, Pedro Amakasu. Japan’s Foreign Aid Policy in Africa: Evaluating the TICAD Process. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014. DOI: 10.1057/9781137493989.0006.

After reviewing past relations between Japan and Africa, the chapter turns to an historical analysis of Tokyo International Conference on African Development (TICAD) intertwined with Japan’s aid policy with Africa with external events providing background. The analysis relates to the guidelines, implementing policies and action plans from each conference between 1993 and 2013.

It aims to evaluate whether the terms of multilateral content (Ampiah 2010: 418) between Japan and Africa to fulfill TICAD’s primary objectives, that is, to promote high-level policy dialog between African leaders and their partners and to mobilize support for African-owned development initiatives through challenging the recipient’s development philosophy, are feasible or not following the advent of Asian development cooperation partnerships.

Paradoxically, the analysis suggests increasing efforts by Tokyo to incorporate the African development agenda into TICAD as follows: the UN New Agenda for the Development of Africa in the 1990s (1993), the Cairo Agenda (1995), the DAC New Development Strategy (1996), the Millennium Partnership for the African Recovery Program (MAP) that emphasizes ‘good governance’, the Omega Plan (2001), focused on ‘economic growth through infrastructure, education, human resource development and agriculture,’ and finally the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD) (2001) agenda (Rukato 2010: 15; Yoshizawa 2013: 392).

All these agendas suggest a new form of cooperation between TICAD and Africa. As the next chapter will show, this cooperation has not always translated into higher Official Development Assistance (ODA) disbursements, stronger trade ties or foreign direct investments (FDI) from Japan to African recipients. Japan’s passive attitude contrasts with that of China and other emerging donors. The New African Initiative (2001: 3), which merged MAP and the OMEGA Plan, observes that to date ‘global partnerships were not based on shared responsibility and mutual interest’. Perhaps the problem is neither within TICAD itself nor in the Japanese development model. In fact, the ‘New African Initiative’ (2001: 28) acknowledges the similarities between the Japanese development model and the Chinese one. Rather, the problem might be in Japan’s altruism that follows the old paternalistic Western aid mould (Eggen and Roland 2014: 99–101).

Historically, Japan obtained its first information on Africa during the Meiji era (1868–1912). Japanese knowledge of Africa was mostly based on Western values and ideology, which tended to underrate African culture and society, thus undermining Japan’s relations with Africa to the present day (TCSF 2005: 3–4).

This was the context when Japan first began dipping its toe into Africa in the 19th century when a Japanese trading company, Mikado Shokai, set up a branch in Cape Town (Ampiah 2011: 269). In 1918, Japan established its first consulate in SSA, in Cape Town (Mori 2001). From the 1920s to the 1960s, Japan’s trading ties with Africa spread, in particular to British and Portuguese colonies (Ampiah 2011: 277; Carvalho 2006: 147–150). Economic assistance, although negligible, was used to appease newly independent African states that applied Article 35 of General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) to Japan.

The oil crisis awakened Japanese interest in Africa’s natural resources. Thus, following the first official visit to Africa by a Japanese foreign minister in 1974, Tokyo imposed limited sanctions on South Africa. This reflected an important adjustment in Japanese foreign policy, and was a response to requests from bordering states within the Organization of African Unity (OAU) against the Apartheid system (Osada 2003: 49). Also, in line with the ‘all round diplomacy’ of Prime Minister (PM) Yasuo Fukuda, economic cooperation and grant aid was doubled to Africa (Alden 2003: 9). In the 1970s, Japanese assistance still consisted of long-term loans, rather than grants to fund economic infrastructure programs in recipient countries, revealing Japan’s self-interest. Cornelissen (2004:119) interpreted this as evidence of a mercantilist aid program or of securing its regional geo-economic interests while minimizing political costs (Nester 1992: 233–239). Japan’s alliance with the United States locked it into the Cold War structures to contain communism beyond Asia. Although in the 1980s Japan’s ODA was used for ‘recycling’ its trade surplus (Ohno 2014), commercial ties with Africa were gradually becoming insufficient to explain its aid activities as decolonization struggles, famine and drought demanded more adjustments to its foreign aid policy (Inukai 1993: 260; Kato 2002: 115; Lancaster 2007: 119–120).

Emergency relief from Japan to the Sahel, Eastern and Southern Africa during the Suzuki Zenko years served to bring African criticism of Japan’s trade and political relations with the ‘White Africa’ minority regimes (Namibia, Portuguese Africa, Rhodesia, and South Africa) into greater relief, while protecting America’s strategic political and security interests in the region as well its own desire for international acceptance and prestige (Ensign 1992: 21; Morikawa 1997: 171, 180, 186; Yasutomo 1986: 87). Accordingly, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan (MOFA) used US requests as leverage to improve its bargaining position vis-à-vis the Ministry of Finance (MOF) to increase ‘strategic aid’ to Egypt and Sudan in line with Tokyo’s comprehensive security policy faster than it would have, had there been no request from the United States (Orr, Jr. 1990: 107, 117–118).

Within international relations, the end of the Cold War not only accelerated peace in numerous conflict-affected countries, such as Ethiopia, Angola, Mozambique, and Namibia as both super powers strategically downgraded Africa, but also contributed to democratic transition in Liberia, Chad, Somalia, and Zaire and forced the end of apartheid in South Africa (Thomson 2010: 165–167). The failure of World Bank and IMF neoliberal economic policies through structural adjustment lending (SAL) introduced in the mid-1980s highlighted the development challenges the continent had to face (TICAD 1993: 1). Western donors’ reluctance to aid African countries, also referred to as ‘aid fatigue’, placed Africa on the sidelines of market-based globalization, which had a substantial impact on African socioeconomic conditions (Takahashi 2000: 13). From 1977 to 1991, Japan announced five consecutive medium-term targets of ODA, under which Japanese ODA would expand beyond Asia to assist African countries, eventually becoming the top’s world donor. Japan also supported the UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) on the social dimension of structural adjustment. Tokyo hosted the fifth meeting on social dimension of structural adjustment (SDA) in SSA in October 1991, aiming to ease ‘the implications of policy and budgetary shifts for poor vulnerable groups’ (UN-ECA 1992: 5). Notwithstanding Tokyo’s efforts, the perception of Japanese foreign aid policy as being mercantilist with an overemphasis in the Asian region persisted.

The political global context of the 1990s presented Japan with an opportunity to change the negative image Africa had of it, and to pursue a foreign policy agenda independent of the United States in the post-Cold War international system (Omuruyi 2001: 123).

Linked to this, there was also a mixed coalition of domestic interests, such as the demand for Africa’s resources, the need to open new markets, aspirations of international leadership and major power status and humanitarian concerns (Alden and Hirano 2003: 1; Omuruyi 2001: 123). It is worth recalling that each TICAD conference has contributed toward maintaining the focus of the international community on African development during periods when Africa no longer was at the center of global politics.

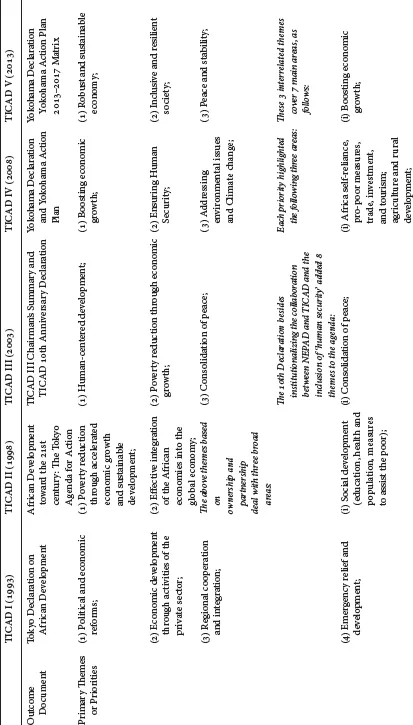

TICAD I in 1993 was hosted after the end of the Cold War amid widespread poverty and problems of governance; TICAD II in 1998 coincided with the Asian financial crisis; TICAD III in 2003 was held in the post-September 11 terrorist attacks era and TICAD IV in 2008 was convened in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. Finally, TICAD V in 2013 was held in the aftermath of Great East Earthquake (2011), with African leaders calling for TICAD to define its approach with private financing emerging countries as the new driving force in addition to ODA (MOFA 2013: 3). At this stage, it is useful to examine the primary objectives and development guidelines during the five TICAD conferences held so far, summarized in Table 1.1.

TICAD I

In October 1993, Japan convened the first-ever global conference on Africa. It drew more than 1,000 participants from 48 African countries, 13 donor countries including the European Community (EC), international organizations, and other civil society organizations (CSO). At the Conference Declaration all participants recognized the ‘continued fragility and vulnerability of Africa’s political and economic structures and situations that inhibit the achievement of sustainable development . . . agree that foreign aid has an impact on development, its role is only supplementary’ (TICAD 1993: 1). All these problems and doubts were echoed in the Tokyo Declaration on African Development of TICAD I, which stated as its primary objectives (TICAD 1993: 1–4):

1Political and Economic Reforms

2Economic Development through Activities of the Private Sector

3Regional Cooperation and Integration

4Emergency Relief and Development

5Asian Experience and African Development

6International Cooperation

The TICAD Declaration launched the basic principles (ownership by African self-help efforts and partnership by the international community in support of such ownership) on which TICAD would evolve and progress (Ampiah 2012: 173). However, the follow-up lacked guidelines to carry out the ‘successful examples of the Asian development experience’ against the adjustment-based strategy of the 1980s, which Japan supported until the early 1990s (Stein 1998: 28; Kasongo 2010: 112). At TICAD I, all participants acknowledged the relevance of experiences in Asia, illustrating the importance of TICAD’s state-led policies as an engine of growth and development (Olaniyan 1996: 142; Ampiah 2012: 172). However, it was too soon to endorse Asian experiences, as participants felt ‘no one model of development can be simply transferred from one region to another’ (TICAD 1993: 4). Another objective lacking substance was the priority given to ‘emergency relief and development’, clearly showing Japan’s unfamiliarity with security matters due to constitutional obstacles (Ochiai 2001: 42), as both Japan and its partners’ roles are unclear. Other limitations at TICAD I derived in part from within Japanese bureaucracy and ministries, in part from within African and international communities (Kasongo 2010: 202–205). Still, TICAD’s emphasis on stability and security as prerequisites to sustainable development at an international level and the support Japan (as the first developed country) offered for South–South Cooperation (SSC) at TICAD through sharing Asian experiences (UN 1993: 5; CPD 2014: 14), provided hope to African leaders at a time when they most needed it.

TABLE 1.1 Primary themes or priorities in the outcome documents from TICAD I to V

TICAD II

Amidst the East Asian economic and social crisis in October 1998, TICAD II welcomed 80 countries (including 51 African, 10 Asian, and 16 donor countries), and international organizations. For Tokyo the lessons learned from structural adjustment policies and its negative effects in Africa required action by Japan to reduce the collateral damage of globalization in Africa (Takahashi 1999: 144–147).

Behind Japan’s altruist gesture was its desire to show the international community that it was a global state (ibid.). Naturally, Africa was a central partner. On the basis of the now-formalized principles of ownership and partnership, TICAD pursued action-oriented objectives for economic and social development: poverty reduction to raise the living standards of African countries. In contrast to the first conference, TICAD II clarified the concept of ownership based on the Cairo Agenda (1995), which enhanced African countries’ roles in pursuing their own set of priorities in partnership with Africa’s development partners. Another difference is that TICAD I was broader in its primary objectives but limited in its development approach. Hence the ‘Tokyo Agenda for Action’ (TAA) established an overall framework for cooperation in Africa with more than 370 potential development programs and projects (Toda 2000: 52–54), including the ‘List of Ongoing and Pipeline Projects for African Development’. The TAA (MOFA 1998) was divided into two main themes, as follows:

1‘Poverty reduction and integration into the global economy through accelerated economic growth and sustainable development’.

2‘Effective integration of African economies into the global economy’.

To accomplish the above themes the Agenda identified several approaches, such as ‘strengthening coordination’, ‘regional cooperation and integration’, and ‘south–south cooperation’, to break the cycle of instability, poverty, and inequality. These approaches were aimed at increasing African ‘capacity-building’, ‘gender mainstreaming’, and ‘environmental management’. Finally, an action plan incorporated the concepts of the New Development Strategy of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development- Development Assistance Committee (OECD-DAC) of 1996 to implement guidelines for development between African countries and their partners based on specific goals. With this method, TICAD aimed for a results-oriented approach with numerical targets. As Eyinla (2000: 225–227) notes, the TAA’s ambitious agenda turned out to be its biggest problem. Although Japan announced a new assistance program based on the ‘Action Plan’ there were at least three major difficulties: first, the lack of cooperation and coordination between African states and donors; second, the recipients’ inadequate infrastructural facilities and low aid absorptive capacity to attain the Agenda goals; and third, the economic and social asymmetries among the African states and the need for political will and commitment to pursue the Action Plan. The latter was by far the greatest challenge of all (ibid.).

TICAD III

In September 2003, TICAD III welcomed 23 heads of ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- 1 The Evolution of TICAD over the Last 20 Years

- 2 Japanese ODA Through the Five TICAD Conferences, 19932013

- 3 TICAD: A Partner or a Partnership Problem?

- 4 Japans African Diplomacy in Africa: The Interaction of External and Internal Factors

- 5 Japans SouthSouth Cooperation and Triangular Cooperation in Africa: Implications for TICAD

- 6 TICAD in the Context of Foreign Aid Policies of Emerging Powers

- Conclusion

- References

- Index