eBook - ePub

Comparative Welfare Capitalism in East Asia

Productivist Models of Social Policy

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The author aims to develop conceptual refining and theoretical reframing of the productivist welfare capitalism thesis in order to address a set of questions concerning whether and how productivist welfarism has experienced both continuity and change in East Asia.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Comparative Welfare Capitalism in East Asia by Mason M. S. Kim in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Development Economics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

What is the precise nature of welfare arrangements in capitalist East Asia? Are East Asian welfare states suitably fitted into the tripartite framework of liberal, conservative, and social democratic models developed by Esping-Andersen (1990)? If not, is there an overarching East Asian welfare model, just as many Asian scholars think of social policy in East Asia as being primarily “productivist” (Holliday 2000)? If the so-called “productivist” model is compelling and acceptable, what are the main characteristics of this model? Is it fair to assume that productivist welfarism has not experienced paradigmatic changes and therefore the key features are mostly identical among East Asian newly industrialized economies (NIEs)? Or if East Asian welfare states have evolved into a number of subtypes with systematic variations, what are the driving forces behind these variations? In short, how can we understand the presumed continuity and change of today’s East Asian welfare regime?

In fact, such questions regarding East Asian welfare capitalism are by no means new in comparative welfare research. The surge of research interest in East Asia that has grown over the last two decades started with attempts to explain how East Asian NIEs could manage to combine remarkable economic dynamism with low rates of taxation and welfare spending while exhibiting impressive achievements on key quality-of-life indicators such as infant mortality, life expectancy, and literacy. East Asia’s unique experience has even propelled ideological debates between right- and left-wing politicians in the West. The Labour Party in Great Britain, for example, viewed East Asia as a role model, highlighting the importance of the active role of the government for the simultaneous promotion of economic growth, social cohesion, and welfare standards. By contrast, the Conservative Party of Great Britain saw East Asia as a good example that illustrates how the creeds of neoliberalism such as individual self-reliance and low government spending can be essential, not only for economic productivity, but also for a financially sustainable social security system (White and Goodman 1998, p. 3; Ramesh and Asher 2000, p. 3). Noteworthy in either of these conceptualizations of East Asian welfare states is that the “miracle” was largely parallel with a relatively low spending level. Indeed, East Asia’s welfare expenditures – measured either as a percent of gross domestic product (GDP) or as a portion of total government expenditure – are much lower than those of most advanced European countries and even Latin American developing countries (Segura-Ubiergo 2007; Haggard and Kaufman 2008).

Yet, what makes East Asian states distinctive is not only the low level of welfare spending, but also the pattern of social policy development. Unlike other advanced capitalist societies where social security is the major policy area of public expenditure, most East Asian states invest heavily in human capital formation, such as education and job training, as part of an economic development strategy while being less willing to spend on other “protective” areas, including pensions, health insurance, and social assistance. East Asian NIEs have certainly placed more emphasis on the “productive” role of social policy than on the “protective” effects (Rudra 2008). The primacy of this productivist tendency has attracted considerable research interest, providing important scholarly insights to those like Holliday (2000) who proposed the so-called “productivist welfare capitalism” (PWC). Undoubtedly, the PWC thesis offers a compelling account of East Asia’s welfare state development as an exercise in East Asian “exceptionalism” (Peng and Wong 2010, p. 658). At the same time, however, questions about the validity of the productivist welfare theory have risen recently as new “protective” social policy initiatives were introduced in several East Asian countries like South Korea (hereafter Korea) and Taiwan. In these countries, the scope of social protection has substantially broadened (Choi 2012).

Thus, this book aims to develop conceptual refining and theoretical reframing of productivist welfarism to address a set of questions concerning whether and how welfare capitalism has experienced both continuity and change in East Asia. The remainder of this chapter briefly reviews debates on the issue of East Asian welfare types, including Holliday’s description of productivist welfare capitalism, and then presents the main arguments of the book. An explanation of these terms, scope, and methods used in each chapter follows.

A. Debates on the East Asian welfare type

Since the publication of Esping-Andersen’s (1990) book entitled Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism that presented a widely cited and influential threefold typology of social democratic, conservative, and liberal welfare regimes, the East Asian model of welfare capitalism has become an increasingly important field of comparative welfare studies. Without doubt, the understanding of similarities and differences of welfare states in a language of categorization is important because welfare modeling provides a key route to the conceptualization of socioeconomic and political conditions for welfare state development (Wilding 2008). As part of this effort, some scholars have attempted to explain how individual East Asian cases fit into one of Esping-Andersen’s three types of welfare regimes (Esping-Andersen 1997; Ku 1997; Kwon 1999, for example). However, such an approach was immediately criticized by those who raised questions as to how it would be suitable and possible to understand East Asian welfare by using a framework developed in the Western context.

Actually, efforts to conceptualize the unique experiences of East Asian welfare development (or underdevelopment) had already begun in the 1980s among those who investigated cultural determinants with a focus on the impact of Confucianism as a distinct driving force behind the overall course of East Asian welfare. Chow (1987) explored cultural and historical differences between the West and China with respect to the role of kinship in providing welfare support for family members. Other researchers expanded the practice of cultural analysis beyond the Chinese case. The most well-known perspective of this sort includes the concepts of “oikonomic welfare states” (oikos being Greek for “household economy”) and “Confucian welfare states” that were introduced to describe how Confucian doctrines have influenced the economic success and social policy in Hong Kong, Singapore, Taiwan, and Korea (Dixon and Kim 1985; Jones 1990, 1993; Goodman and Peng 1996; Rieger and Leibfried 2003). According to the historical-cultural perspective, East Asian societies have strongly adhered to the Asian values such as filial piety, respect for authority, loyalty, patriarchy, and the close family and kinship ties that would be fundamentally incompatible with the Western style of socioeconomic and political systems. The long-lasting Confucian tradition of patriarchal responsibility for care and protection of the family household has therefore hindered the development of Western conceptions of the welfare state in East Asia. Hence, East Asia’s low level of welfare expenditure is most often attributed to “familialism” that has produced an aversion to public social services.

However, the cultural approach was soon criticized by those who argue that the East Asian region is too diverse to lend itself to easy generalization (Ramesh and Asher 2000, p. 7). Indeed, Confucianism cannot explain why various welfare programs such as pensions, health insurance, and unemployment benefits that are at odds with the core “Asian” values have developed in various forms over time across East Asia. Furthermore, the cultural approach suffers from methodological limitations, including lack of indicators to conceptualize and measure the influence of culture. After all, the concept of Confucian welfarism, with its emphasis on family obligations, education, and social harmony, became secondary or even marginal in the field of comparative welfare research (Hudson, Kühner, and Yang 2014, p. 303).

Another important stream of East Asian welfare studies has come from those who have examined the role of growth-oriented soft authoritarian states. This approach was mainly predicated upon the theory of a developmental state that is “a shorthand for the seamless web of political, bureaucratic, and moneyed influences that structures economic life in capitalist Northeast Asia” (Woo-Cumings 1999, p. 1). Put differently, a developmental state is one that plays a strategic role in economic development with a competent bureaucracy that is given sufficient policy measures to take initiatives and operate effectively. Johnson (1982) portrayed Japan as a pioneer model of the development state, arguing that the post-war Japanese bureaucratic autonomy was central in achieving national economic development. He stated that the Japanese government tightly regulated the financial market and channeled funds into strategic industries for rapid industrialization. This developmental–statist model also affected the industrialization strategies of Korea and Taiwan where the soft authoritarianism– capitalism nexus emerged in the 1960s (Johns 1987; Amsden 1989; Haggard 1990; Wade 1990).

Strongly influenced by the developmental state approach, a number of studies explored how the emergence of welfare politics was intertwined with the socioeconomic conditions in East Asia. Since Midgley (1986) presented the concept of “reluctant welfarism,” a group of scholars joined in the debate, arguing that social policy has been largely subordinated to the overall developmental goal of rapid economic growth. Deyo (1989, 1992), for example, asserted that the underdevelopment of social welfare in the tiger economies was closely associated with export-oriented, labor-intensive manufacturing that required cheap and disciplined labor for fast growth in the 1960s and early 1970s. Tang (2000) added that East Asian governments established a range of social welfare programs, including education, social security, health insurance, housing, and social services, for the promotion of labor stabilization and political legitimization of the authoritative regimes. In short, East Asian welfare states featured low public social expenditure, relative labor market flexibility, limited universalism and egalitarianism, and the application of social security as an instrument to target politically important interest groups (Tang 2000; Midgley and Tang 2001; Kwon 2005; Hudson, Kühner, and Yang 2014).

Developmental welfarism that viewed the role of social policy as a means to foster nation building and political legitimacy of undemocratic regimes has been later extended in a more nuanced manner by Holliday (2000, 2005), who proposed the concept of “productivist welfare capitalism” (PWC). Whereas the PWC thesis was almost identical with the developmental welfarism approach, in that social policy is understood as subordinated to economic policy objectives, the productivist welfare approach emphasized the dynamics of capitalist market economies over the political need of autonomous states (Choi 2013, p. 212).

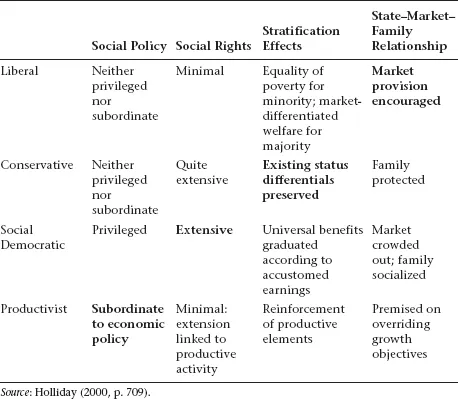

A great deal of Holliday’s productivist welfare approach involved criticism of Esping-Andersen’s Three World typology. Drawing upon Polanyi’s (1944) view, Esping-Andersen asserted that different types of historical class coalitions produced distinctive patterns of social rights, social stratification, and state–market–family relations and in turn largely determined the main features of welfare models. The class coalition of the working class and farmers, according to Esping-Andersen, shaped the “social democratic” model of welfare capitalism in the Nordic countries that promoted an equality of the highest standards and the principle of universalism. In the continental European countries, political conservatives formed “reactionary” alliances, which led to the “conservative” model of the welfare state. The Anglo-Saxon countries, where the “liberal” model emerged, did not experience a class coalition and with only a modest level of welfare benefits becoming prevalent. As such, based upon three criteria, including “the quality of social rights,” “social stratification,” and “the relationship between state, market, and family,” Esping-Andersen identified a liberal world prioritizing the market, a conservative world defined by status, and a social democratic world focused on welfare (Table 1.1).

According to Holliday, however, the identification of East Asian welfare capitalism requires one more criterion because the three-model typology does not fit the reality of East Asia. First, the influence of capitalists in East Asia was not strong enough to fuel the formation of “liberal” welfare states. Indeed, capitalism in East Asia was crafted historically as part of the process of state-led industrialization (Cumings 1984). Second, there was no powerful landlord class in East Asia during the post-war era that would have promoted the formation of “conservative” welfare states (Kay 2002). Third, East Asia did not have a coalition combining the working class and farmers, which might have favored the development of “social democratic” welfare states (Kamimura 2006, p. 316). Given this peculiar historical context, the East Asian welfare regime needed another yardstick to identify its nature; thus, Holliday presented “the subordination of social policy to economic policy objectives” as the fourth criterion for welfare state modeling.

Table 1.1 Four worlds of welfare capitalism

The core argument of the productivist welfare thesis is that social welfare in East Asia has been mainly determined by productivist principles of minimal social rights with extensions linked to productivist activity, reinforcement of the position of productive elements such as education and job training in society, and state–market–family relationships directed toward growth (Table 1.1). Due to the belief that the government’s social welfare spending gives rise to a burden on the economy and consequently undermines international price competitiveness, family welfare and/or occupationally segregated corporate welfare have become the major methods of social security provision in East Asia (Song and Hong 2005, p. 180). As such, Holliday and the advocates of productivist welfarism maintain that East Asia’s economic strategies have led the governments to avoid any strong financial commitments to social welfare, while expanding investment in education, in order to build a more competent labor pool to facilitate national economic growth. This is why few right-based welfare programs were developed during the fast-paced industrialization period of the 1960s to 1980s (Pierson 2004, p. 11).

Undeniably, the productivist model reflects the key features of East Asian welfare capitalism that distinguishes East Asia from other parts of the world. However, despite its significant contribution to the welfare state debate, productivism per se offers little to explain why the pattern of adoption and extension of PWC has not been uniform in the region (Kim 2010). Indeed, it is not hard to observe the surge of institutional variation and dynamism of East Asian welfare regimes since the late 1990s (Peng and Wong 2008, 2010). Although some states like Singapore, Hong Kong, and Malaysia remain productivist by fostering individual savings schemes which emphasize the self-help principle, other nations have developed redistributive social insurance schemes with an expectation of risk-pooling effects. An expansion of this type is remarkable in Korea and Taiwan, among others. Also, another group of East Asian states, including Thailand and China, have pursued a dualist approach, embracing both social insurance and individual savings schemes simultaneously. In other words, the scope and extent of social policy protection have been substantially broadened in some countries, although it is equally true that there has been little paradigmatic change in the philosophy and the fundamentals of productivist welfarism. To be sure, productivist welfare states have experienced both continuity and change (Kwon and Holliday 2007; Peng and Wong 2008; Choi 2012). This trend raises a question as to whether it is still useful to characterize East Asian welfare states as productive. If productivism is still a key unifying theme, how can the recent growth of social protection programs be understood within the analytical framework of PWC?

There are many inter-regional comparative analyses that look at contrasting features between East Asia and other parts of the world, but few studies have explored the issue of intra-regional variation of East Asian welfare regimes in a systematic manner. Thus, this research aims to show that, despite the similar nature as productivist welfare states, East Asian economies have evolved into three different types of productivist welfarism. To test this argument, this book first presents a three-model typology of PWC and then investigates the political–economic conditions under which systemic variation occurs.

B. Arguments in brief

(1) Three models of productivist welfarism

Productivist welfare capitalism offers a captivating account of welfare state evolution in East Asia, viewing the provision of social security benefits as being subordinate to the imperatives of labor production, human capital formation, and sustainable economic growth. However, despite the continuity and steadiness of its productivist credentials, the institutional design and implementation of PWC are not identical in the region. This variation began in the post-war years and has become more significant since the 1997 Asian financial crisis (Kwon, H. 2009). Indeed, the financial crisis was a momentous watershed not only because it hit the region hard and wide, but also because it led many of the East Asian states to realize the importance of a social protection mechanism. For example, the expansion of social insurance plans and public assistance programs is more prominent in Japan, Korea, and Taiwan, whereas compulsory individual savings schemes play a leading role in Singapore, Malaysia, and Hong Kong. Unlike these two groups, China and Thailand are deliberately pursuing a mixed system, combining social insurance and individual savings.

Given this presumed variation, the current single-lensed productivist welfare approach does not fully address the question of whether and why East Asian productivist welfare states ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Institutional Variation in Productivist Welfare Capitalism

- 3 What Drives the Institutional Divergence of Productivist Welfare Capitalism?

- 4 Three Cases of Productivist Welfare Capitalism

- 5 Conclusion

- Appendix

- References

- Index