eBook - ePub

Fandom, Image and Authenticity

Joy Devotion and the Second Lives of Kurt Cobain and Ian Curtis

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Fandom, Image and Authenticity

Joy Devotion and the Second Lives of Kurt Cobain and Ian Curtis

About this book

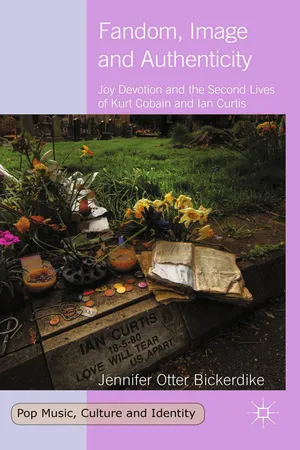

Kurt Cobain and Ian Curtis. Through death, they became icons. However, the lead singers have been removed from their humanity, replaced by easily replicated and distributed commodities bearing their image. This book examines how the anglicised singers provide secular guidance to the modern consumer in an ever more uncertain world.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Fandom, Image and Authenticity by Kenneth A. Loparo,Jennifer Otter Bickerdike in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Joy Division tribute bands

The main facts within the mythology of Joy Division remain unchanging, there will always be a handful of truisms which time cannot erode. Dates of birth, where the band recorded songs, shows performed, and place of death for Curtis are unshakeable, known. Yet the theme of whom and what the band was differs depending on location. Thus Joy Division continues to evolve long past the suicide of Curtis, the demise of the band, the release of any new material.

One aspect showcasing the ‘aesthetic interest’ (Kracauer, 1995: 76) of the legendary group is the proliferation of Joy Division tribute bands around the globe. The original line-up of Curtis, Hook, Morris and Sumner has become familiar to countless fans via mediated replication, such as YouTube clips, fictional movies of the group and interviews. The tribute band bridges the gap between the virtual of such recorded and repeatable mediums with the possibility for live, new interactions and occurrence, as groups around the world attempt to (re)create the relationship of performance – an experience both audience and musician have only known through dated recorded image. Tribute bands also offer a form of resistance that opposes the traditional models of audience as a passive consumer, allowing the fan to become both performer and producer of culture, implying a creative imagination of social possibilities – fans as self-organised social groups that seize on particular forms (such as inactive rock bands) as vehicles for newly revised and experienced creativity via old nostalgia.

Tribute bands and cover bands are not to be confused. A cover band will play a wide range of songs from a variety of artists. A tribute band, ‘dedicates itself wholly to the music of one particular group … the goal [being to] replicate, as closely as possible, in both sound and appearance, another, more famous band’ (Kurutz, 2008: 40).

Currently, there are at least 28 known, active groups dedicated to playing solely the songs of Joy Division on a regular basis.1 These bands exist in areas as diverse as San Francisco, Los Angeles, Cleveland (OH), Israel, Berlin, New Zealand, Italy, and Manchester, England, the home of the original Joy Division line-up (and now the stomping grounds of tribute act Joyce Division, a cross-dressing man who performs arrangements of the group’s canon in a cabaret style). The exposure via the World Wide Web has allowed Joy Division to reach far and wide, going in death far beyond the limited cities the band ever actually toured during their four years in existence. Joy Division has amassed a seemingly ever-growing audience posthumously through mass media.

During their short time as an active entity, the group toured the United Kingdom, only venturing out to a handful of other European countries: France, the Netherlands, Belgium and Germany. Their current fan base extends around the globe, with tribute bands in far-flung spots like Mexico City declaring, ‘We must keep the legacy of Ian Curtis alive’ (Ernesto, 2008)! Rolling Stone tribute band biographer Steve Kurutz (2008: 46) notes, ‘In the tribute world, you can go to places reality cannot possibly go’. The paramount importance placed on ‘keeping the legacy alive!’ shows ‘no independent thinking … from the audience: the product prescribes every reaction: not by its natural structure’ (Adorno and Horkheimer, 1942/1972: 137). The more posts, ‘news’ and proliferation Joy Division receives, the more influential they become, their relevance magnified by the grinding wheels of the culture industry. Tribute band members depend on this, dually for rectifying their role as imitation and for their own identity as musician/performers. Their continuous existence rests on both ‘appreciating the [original] band’s music [and being] … an equal part … seduced by the mythology’ (Kurutz, 2008: 93–4). Interviews with tribute band members exemplify this deep-seated belief in the integral significance of Joy Division. Ernesto, the Curtis figure and leader of Varsovia 54 in Mexico City, argues,

I think that Joy Division [is experiencing] something similar to what happened to Velvet Underground, only 20 years later. Velvet Underground broke up, and they were not famous, and afterwards everyone is referring to them as ‘influential,’ the Ramones, Television, many bands. The same thing happens to Joy Division. It is suddenly in vogue to say, ‘I am influenced by Joy Division’, ‘we want to sound like Joy Division’. [Now] there are many bands that sound like Joy Division: Interpol, The Editors, many others. I hope that in Mexico this is not a transient trend, I hope that it is not just cool for a while and then it disappears.

(Ernesto, 2008)

Dave Tibbs, lead singer/Ian Curtis figure for San Francisco-based tribute group Dead Souls, provides another excellent example to illustrate the deep and often personal investment in this mythology; his story provides an personification of the Adorno/Horkheimer theory of culture industry personified.

The 43-year-old Tibbs never saw Joy Division, nor has ever been to Britain. However, Tibbs (2007) believes Dead Souls are providing an essential experience to fans, allowing them at first hand to see a group ‘perform in the spirit Joy Division performed in … bring[ing] an understanding to the band’. Tibbs believes that the ‘Martin Hannett2 versions of Joy Division songs are completely different from the live shows [which were recorded and have now been widely distributed]’ (ibid.), and offer a ‘profound experience’, that ‘ need[s] to be represented, understood and explored’ (ibid.).

Curtis has had an indelible impact on every aspect of Tibbs’ life: he dresses daily in clothes directly influenced by the wardrobe pictured in photographs of the dead singer; he works with displaced mentally handicapped people, a career path similar to that of Curtis; even when having a haircut, Tibbs brings along the required picture of Ian, in order to get a matching look. Tibbs is the living incarnation of what Boorstin (1980: 192) perceives as the manner that, ‘We have become thoroughly accustomed to the use of images as invitations to behaviour’. Kurutz (2008: 40) agrees, saying, ‘tribute bands are a simulation, but at the same time they are affectingly genuine; the musicians aren’t guided by commercial interests or a record company marketing strategy, but in most cases by a sincere desire to perform’. This desire to (re)capture an imagined, created notion of ‘authentic’ is the foundation of the tribute band. Yet paradoxically, this very form of ‘self-expression’ depends on ‘band members … pretending to be other people’ (ibid.: 41). Perhaps in some cases, such as Brooklyn, New York’s Y’all Lost Control, it is not just about the look; it is the values and attitudes attributed to Joy Division Y’all are trying to mimic, a DIY,3 devil may care, art for art’s sake ethos that has come to define Joy Division. The viewpoint of Y’all’s guitarist and vocalist, Cory Watson (2012), explains this idea, claiming,

Joy Division is all about the song and emotion. They wrote incredible songs that were unique yet born out of emotions we can all relate to. They were able to go so deep with the emotions of the songs and reach a raw, visceral place that had yet to be explored. They didn’t care about musical recording/production other than they wanted the feeling to come across in the recordings. They also weren’t very skilled players but they came together and brought unique ideas to the table and told a great story about chemistry within a group and the creative process.

Another Brooklyn tribute act shares this attitude, as illustrated in their vinyl pressing and live performances of Joy Division classics. Jah Division (2007) offers a dubbed version of the classic single ‘Love Will Tear Us Apart’, re-named ‘Dub Will Tear Us Apart’. While the bass line remains somewhat true to the original song, the rest of the tune is presented to include head tripping mellow beats and tranced out guitar work (the video of the group performing on YouTube even offers the classic psychedelic ‘scrambled eggs’ backdrop of visuals). Y’all also distills the key elements of the Joy Division canon, remaking the post-punk songs in a country-and-western format. Watson (2012) notes, ‘this is an idea that intrigues fans of Joy Division but they are also very curious as to how we are going to pull it off’, noting ‘it’s amazing how well these songs translate to the country format’.

Yet Kurutz (2008: 20) asks, ‘Is a Stones tribute band without a guitarist who looks like Keith Richards still a Stones Tribute band?’ The extent of Tibb’s fandom begs this question, would people still be interested in Dead Souls if Tibbs did not look, and, to some degree, act like [they expected] Ian Curtis to?

Tibbs (as well as all of the other 27 front men of the Joy Division tribute acts) has solely experienced Joy Division virtually. His knowledge of the Mancunian foursome comes entirely from listening to recorded music, watching videos and talking to other fans, in his youth, while visiting independent record stores, now, in chat rooms, and on social networking sites like Facebook and MySpace. He also interacts with followers at live shows when his band performs, his engagement with the image and the idea of Joy Division, as a re-envisioned Curtis, one hinging on constant re-invention through social channels.

Tibbs was in several original bands concurrently with his work in the Joy Division tribute projects. However, it is only through his time as ‘Ian Curtis’ that he has been able to play at premiere venues, to have sell-out shows and travel to other cities (and not lose money). The success he has experienced dovetails with what Kurutz (2008: 45) calls the ‘pre-tested entertainment’ factor of tribute bands:

if you like the Rolling Stones, you will like Sticky Fingers [a Rolling Stones tribute band]. On the other hand, if you pay ten dollars to see an original-music act you’ve never heard before, it’s a gamble; you might discover a new favourite artist or spend the night listening to a shrill woman with an acoustic guitar sing fourteen songs about her ex-boyfriend.

As fans will never be able to see the original line-up of Joy Division, tribute bands allow access to the live music experience. As Kurutz notes, ‘at the show, you can stand right in the front, take pictures, dance with friends, meet the band and interact with the music and musicians in a remarkably direct way’ (ibid.). As each of these bands attempts to reconstruct what they envision was the ‘authentic’ Joy Division experience, they simultaneously produce their own collaboration with memory. With each re-watching of a Curtis video, they re-interpret his moves while adding their own unique twist; though they may strive to be ‘genuine’, as Tibbs has his locks sheared to Curtis perfection, it is impossible to capture Manchester 1978 through San Francisco 2014 in exact detail. Benjamin (2008: 12) argues that ‘even the most perfect reproduction of a work of art is lacking in one element: its presence in time and space, its unique existence in the place where it happens to be’.

The Joy Division story has changed, through time, re-telling and the transmission of experiences (such as Tibbs performing as Ian Curtis), to be different in Mexico City today from in New Zealand in 1993 (both places where Joy Division tribute bands exist, for example).

The separate groups also watch, review, criticise and critique each other’s performances, I was repeatedly asked by the bands I interviewed about other Joy Division groups I had seen. Kurutz (2008: 32) noted this pattern, hypothesising that by ‘impersonating a celebrity [one can become] something of a celebrity [in their] own right’. The tribute bands, themselves an evolved reproduction, watching other tribute bands, continue and create a new text, a replication of a replication ad infinitum. The very original look and feel that the bands attempt to create is threatened by their every performance, as each crowd response, video review and interaction changes the dynamic, thus, in itself, evolves the idea of ‘Joy Division’. This leaves the tribute bands with the feasibly impossible task of perpetuating something that their very existence makes futile: every concert brings them further away from any shred of the genuine.

The audience experience of each of the tribute bands reflects this evolution of the Joy Division myth. Fans in San Francisco seeing Dead Souls will have a different cultural reference point for ‘Englishness’ from that of a member of the crowd in London seeing Unknown Pleasures. With these different versions of Joy Division, the politics of who the band truly were have become diluted, even blurred, while the re-envisioning of what the band is continues to change, progress and grow through the continued cyclical interaction of fan and tribute acts, a conglomeration of both entities of audience and tribute members participating in a never ending symbiosis. This global ‘community’ of Joy Devotion is what Kracauer (1995: 76) refers to as ‘the mass and not the people … ; a mass not consisting of a particular individual; instead, an emigration of global beliefs and actions’.

The ‘mass’ watch, re-post, comment and replicate each other’s performances, both audience and bands, exhibiting ‘a current of organic life [which] surges from these communal groups … to their ornaments, endowing these ornaments with a magic force and burdening them with meaning to such an extent that they cannot be reduced to a pure assemblage of lines’ (ibid.). While perhaps not being an exact replica of the Mancunian experience 30 years ago, the performers and participants at tribute shows are creating their own unique entity of Joy Devotion, while dangling from the overarching ideals of the original concept.

Tattoo you – the hyperreal and object fetishism of the body

Embellishing the skin with images belonging to a larger group of signs represents a long-term commitment to a particular set of values inherent in the symbol. Two things are key to note here: first, the image’s meaning may change and evolve as the meaning attached to the picture itself mutates through time and replication. Second, each replica itself is a reproduction, a process that blurs and transfers the original each time it is distributed. The very authenticity and longed-for identity is truly just an homage, a chasing of the shadow of the original.

Fans obtaining a Joy Division or Curtis tattoo before the films 24 Hour Party People, Control and Joy Division were essentially both declaring their pledge to the groups’ supposed air of authenticity while joining a small subculture of devout listeners who still carried the Joy Division torch. The image of a Joy Division specific sign announces inescapable evidence of traits often associated with Joy Division – to the small group of other band followers. The fan obtaining a Joy Division tattoo today has the inescapable legacy of the movie trilogy featuring Joy Division, as well as all the other marketing mechanisms inspired by the re-ignited interest in the post-punkers. Thus their ink contains the newly minted meaning of Curtis/Joy Division from the big screen, a fictionalised entity.

Mike Parkinson, 43, acquired his Joy Division tattoo in 2005.4 His ink features the band’s most well-known song title, ‘Love Will Tear Us Apart’, emblazoned in two-inch high letters across his back. When asked of the significance of his ink, Parkinson (2011) answered,

My Tattoo … I got it coz [sic] I love the song, the words are so meaningful and without sounding a bit OTT [over the top] – I could feel the pain in the words, the way that no matter what this guys [sic] relationship was over and he couldn’t do anything to stop it – like you can love somebody to [sic] much but you can’t make them love you if they don’t anymore … it was just the words of the title are so true – you know what the song means without ever having listened to it. I was on Holiday [sic] just after I had it done and the amount of comments I got was quite amazing and most people I spoke to, who had loved and lost understood the meaning all to [sic] well – as well as a lot of them knowing the song and the band! The meaning to me is knowing a coupe [sic] of points in my life where I’ve been thru [sic] what the guy in the song has been through and I understand it totally – the line ‘There’s a taste in my mouth as desperation takes hold’ – is nothing short of astonishing, describing perfectly the metallic taste we all get when anxiety sets in.

Mike recalls being able to ‘feel the pain in the words’ of the Curtis-penned lyrics, a parallel to the tattoo’s legacy of ‘pain’ as punishment, as well as the actual agony inflicted by the act of getting tattooed, and the ‘punishment’ for ‘lov[ing] somebody to [sic] much but you can’t make them love you if they don’t anymore’ (Figure 1.1). The tattoo underscores the song’s relationship between love and pain, while creating an illustration on the body of matters felt inside.

Mike’s mention of other people ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5

- Chapter 6

- Chapter 7

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index