![]()

1

Excise Taxation in Context

Conventional accounts of the origins of the British fiscal state have an aversion to exploring in detail the advent of markets for debt securities. Most historians agree that in the British Isles the transition from a late medieval demesne-state to a tax state occurred in the seventeenth century, culminating in the Financial Revolution of the 1690s (Schumpeter, 1918; Braddick, 1994, pp. 1–21).1 Yet no major work of scholarship has looked closely at the link between the two. For most scholars what began during the Civil Wars and Interregnum reached fruition only after the Revolution of 1688/1689. Some authors may acknowledge that post-1688 finance was built on pre-1688 practices, but few have attempted to reconstruct these practices in any detail, much less to link them to the Financial Revolution and the new species of public borrowing which financed the eighteenth-century state. Those who have done so at all have tended to locate structural change within the Restoration period (Brewer, 1988, p. 95). By overcoming the significant archival challenges of reconstructing Interregnum experiments in public finance, this book illuminates the origins of the durable institutions, structures and practices that formed the foundations of the fiscal state in the British Isles. More importantly, however, especially in the second decade of the twenty-first century, this study firmly locates the origins of the public debt in Interregnum experiments with excise taxation. Failure to adopt forms of long-term debt associated with post-1688 finance arose not from a lack of familiarity with these instruments, but rather political instability and the spectre of regime change foreclosed the possibility at key moments. This finding has significant implications for historians of early modern Britain and for macroeconomic policymakers looking to prescribe the means of reassuring markets and citizens alike of a state’s ‘credible commitment’ to honouring its public debts.

As Davenant’s reflections in Discourses on the Public Revenues of 1698 should remind modern readers, advising governments about how to best manage their debts is not a distinctly modern preoccupation. The advent of the Washington Consensus, however, has made institution building a priority for nation-states and for supranational and global governance structures. Almost twenty-five years after North and Weingast’s first publication in 1989 of their famous ‘Constitutions and Commitments’ article, historians and economists alike have identified four key elements of ‘credible commitment’. Yet each of these factors—parliamentary control over the public finances, transparency in public accounts, accountability via creditor action and surprisingly deep secondary markets, as well as a stated commitment to maintaining the ‘publike faith’ and the use of common law procedure to adjudicate disputes between taxpayers and the regime—were, in fact, in place during the Civil Wars and Interregnum under the Long Parliament and Commonwealth regimes. But they did not, in themselves, produce credible commitment mechanisms for generating support for long-term public debt. Rather what the first twenty years of the British experiment with excise taxation teaches modern students of its history is that these are ‘necessary but not sufficient’ conditions. Instead there is strong evidence that the most important ingredient in the durability of commitment mechanisms is also the most elusive and contingent: the perception of the stability and permanence of a given regime, whether it be representative and deliberative or monarchical and autocratic.

Four years of archival research for this project uncovered new manuscript material and made possible the re-visitation of known sources that had not been seriously studied for over half a century. Both have yielded a wealth of new information about institutional practices and resistance to them. By drawing together methodological tools employed by historians of public finance, political culture and economic thought, this study assesses what contemporaries learned from successive regimes’ experiments with commodity taxation and elaborates the mechanisms by which the unintended consequences of their actions produced permanent structural and even constitutional change. The Financial Revolution emerges as a product of indigenous institutions and practices, not of presumptive English tutelage to ‘Dutch Finance’.

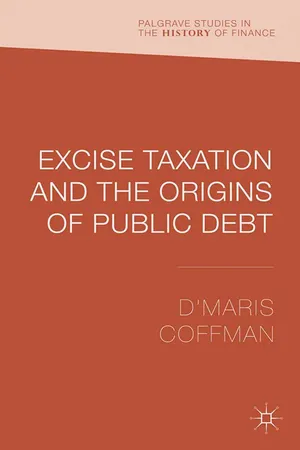

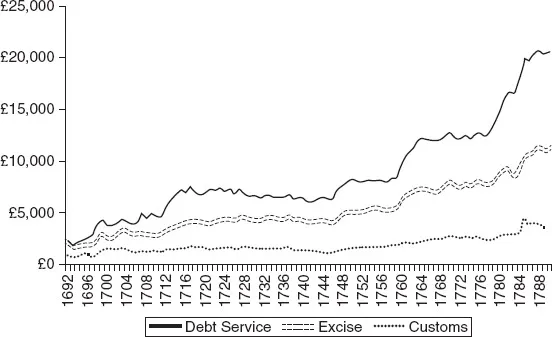

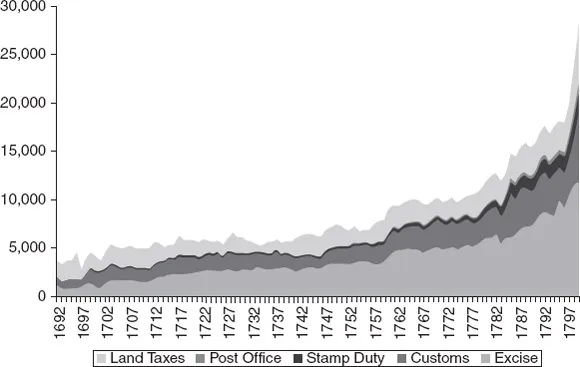

The close connection between excise revenue and government debt service (Figures 1.1–1.3) observable over the course of the eighteenth century arose from the Long Parliament and Commonwealth regimes’ practice of assigning specific revenues to service particular debts (Brewer, 1990; Coffman, 2008). Unfortunately current scholarship follows North and Weingast (1989, p. 821) in ascribing the practice of assigning revenue ordinances to service particular debt instruments exclusively to the post-Revolutionary period (Murphy, 2013). The practice actually began during the 1640s under the Long Parliament, and was fundamental to the manner in which public debt instruments were issued. Creditors both large and small understood the regime’s debts to be secured by revenue ordinances, and would refuse to lend unless they believed the collateral to be sufficiently unencumbered and judged the security to be ‘good’ (Coffman, 2008). The parliamentary regime took very seriously indeed the need to maintain the ‘publike faith’. It is no exaggeration to say that the propensity for creditor action that Murphy (2013) ascribes to the post-Revolution period can also be perceived in the Interregnum.

Figure 1.1 Excise and customs revenues versus debt service charges, 1690–1790

Source: Mitchell, 1988, pp. 575–580. Figures in thousand £ sterling.

Figure 1.2 Composition of the public revenues, 1692–1799

Source: Mitchell, 1988, pp. 575–580. Figures in thousand £ sterling.

Figure 1.3 UK national debt, 1692–1799 (funded and unfunded)

Source: Mitchell, 1988, pp. 575–580. Figures in million £ sterling.

As the epigram to this chapter suggests, Davenant had perceived in 1698 an essential truth of eighteenth-century British public finance, namely that the public had an almost unlimited appetite for funded debt. Collateralisation of revenue streams as security for annuities with a range of term structures provided the means with which Britain fought a series of costly eighteenth-century wars. Yet this was not the first time the state had needed to raise unparalleled revenues. In its most basic sense, this study addresses how, nearly a half century earlier, a fledgling parliamentary regime dealt with the unprecedented levels of expenditure necessary to fight the Civil Wars and then to secure the Commonwealth and Protectorate’s stature on the international stage. Parliament’s success at imposing on a deeply divided kingdom an extra-legal species of indirect taxation, which hitherto had been constitutionally anathema and politically unpalatable, remains one of the most striking features of the period. The excise and the levels of government borrowing it supported became permanent parts of the Restoration financial settlement, yet that was far from a foregone conclusion. Understanding how and why excise taxation achieved legitimacy, while preserving a sense for the contingent nature of that process of negotiation, speaks directly to broader questions of the possible rhetorics of legitimation available to any regime.

The settlement of excise taxation was contingent. There were powerful forces working against it. Opponents of the excise questioned its legality, offered penetrating critiques of its incidence and proposed ingenious alternatives. Domestic commodity taxation appeared to violate the Tudor conception of the kingdom as the ‘manor of England’, in which the landed voted impositions on themselves to supply their king. For those who wanted to restore a financial regime that can be termed ‘fiscal feudalism’, excise taxation was particularly loathsome. When it did not bear the taint of Dutch republicanism, the excise smacked of continental absolutism. Proponents thought it the ‘most insensible imposition’, but as disaffected royalists, radicals and independents alike pointed out, the taxation of domestic commodities fell heaviest on the poor. Many Englishmen thought the poor should not pay taxes at all. In the mercantile community, the approval of the excise was far from universal. Special interests argued specific excises hurt trade, destroyed fledgling industries and rewarded professional tax collectors at the expense of more productive members of society.

From the perspective of the state, excise taxation proved nicely suited to the evolving English economy and its new commercial society. Under the Commonwealth regime, officials recognised that the excise could be used to expand the fiscal frontier. Historically, the Home Counties and London contributed disproportionately to the king’s revenue. Extending the geographical reach of the state also offered non-fiscal benefits too. Proponents and opponents alike saw the potential for using excise officers to gather intelligence and monitor dissent. Others cited non-fiscal benefits: the excise discouraged consumption of luxuries, promoted social cohesion (by making the poor stakeholders), encouraged the protection and consolidation of domestic industries, enforced a positive balance of trade and gave the regime the capacity to reduce or expand the quantity of coin in circulation.

The excise was adopted in a moment of crisis. Precisely because it was so controversial, the excise required new justifications and created new possibilities. The excise created a contemporary discussion about the principles of taxation that shifted the terms of the debate away from constitutional analogies to domestic realities. During the Civil Wars, this was possible in part because the legality of the excise imposition rested on the ‘necessity’ argument, but also that the ‘ancient constitution’ had been sundered by the regicide. If the ‘manor of England’ was to be reconciled with the Commonwealth regime, then it had to be re-thought. Under the Protectorate, those who wanted to resurrect the ‘fiscal feudal’ model had to contend with the excise in their analysis, if only to discredit it. In the process of that re-thinking and re-negotiation, other models occurred to contemporaries. Most were continuations of older strands in economic thought. Others were novel. Some, such as Thomas Hobbes’ (1991) Leviathan, employed the language of an abstract state. Some reasoned from fundamental principles, others from experience.

Conflicts over the excise reveal the contradictions in Protectorate political culture, but these debates also had long-term consequences. To understand the Restoration financial settlement, historians must appreciate both the importance of retaining the excise and the significance of the constitutional fiction created to do so. How far did the Convention Parliament ‘restore’ the status quo antebellum? If the language of the Restoration Settlement preserved the ‘medieval doctrines of supply’, the reality was quite different. The fiscal innovations of the Interregnum had altered what might be called ‘state structure’. William Petty’s A Treatise of Taxes and Contributions (1662) saw four pirated printings and dozens of references in contemporary economic thought. Excise taxation facilitated a ‘Fiscal Revolution’ in two senses. It catalysed structural change, but furnished a political compromise, which preserved pre-revolutionary discourses of legitimation even as new ones evolved to describe the new underlying realities. Precisely because of that paradox, the fate of the excise was paradigmatic of the Stuart Restoration. At the same time the experiments in public borrowing under the Long Parliament offered a blueprint for what was possible after the accession of William and Mary.

Ninety years after Joseph Schumpeter coined the concept, standard narratives of early modern European state formation remain anchored to his notion of the transition from a feudal demesne-state to the beginnings of the modern tax state. In a very narrow sense, claims for a fiscal Revolution of the Interregnum are uncontroversial. Before the Civil Wars, the Crown relied upon feudal demesne revenues (revenues from Crown lands, forest fines and the proceeds of escheat, aids and the court of wards), prerogative taxation (purveyance, ship money, forced loans, imposts and monopolies), and the great and petty customs. By contrast, the Tudor subsidies (which had been based on contested assessments) and the tonnage and poundage (i.e. parliamentary customs voted to the monarch for life until the reign of Charles I) made up less than a quarter of the total. If the tonnage and poundage duties are re-classed as prerogative taxation after 1628 (when the king began to collect them without parliamentary assent), the proportion is even smaller. After the Restoration, over 90 per cent of the Crown revenue came from parliamentary taxation (Braddick, 1996, pp. 1–20).

This book seeks to explain why that structural change occurred and why it endured. Most narratives of the British tax state sidestep those questions. The conventional explanation for what ‘caused’ the modernisation of the British fiscal system turns on the ‘functional crisis of monarchy’ (Russell, 1979, 1973; Braddick, 1994, pp. 1–10). By the mid-1630s, prerogative taxation had proved inadequate to meet expenditure. Charles had been forced to call the Short Parliament to obtain funds with which to fight the Bishops’ Wars in Scotland. When civil war broke out in England, the Long Parliament needed new revenue sources to pay their armies. First they abandoned the Tudor subsidies in favour of assessments, and then they adopted the excises. In doing so, they pled necessity. They promised to continue these new taxes only long enough to bring the king to heel and to satisfy the debts incurred in doing so. Within the conventional legal framework, these were sources of extraordinary supply, raised to meet extraordinary expenses. How and why did they become a permanent part of the revenue? Explanations that favour ‘functional crisis’ over structural change take for granted that temporary fiscal expedients would inevitably be made permanent.

This study demonstrates that excise taxation provided the engine of Schumpeter’s structural change and the catalyst for a shift in ideological justifications of parliamentary taxation. This interpretation hinges on three related claims. The first is that excise taxation proved far more successful than anticipated, both in its capacity to raise needed funds and in the speed with which the parliamentary regime was able to create a durable and disciplined revenue establishment. Had it failed to accomplish both, it would not have endured. Second, the relative regularity and transparency of collection, the high degree of centralisation and new methods of auditing and control permitted the development of new short-term debt instruments, which could be secured by the excise ordinances and priced by the market. The market pricing of short-term debt broadened and deepened credit markets. Third, the excises had no legal precedent (or dubious ones at best) and thus required new justifications. By voting to retain the excise in exchange for the permanent abolition of the court of wards, the Cavalier Parliaments maintained a constitutional fiction based on medieval doctrines of supply. In effect, the excise offered a solution, acceptable both to adherents of an older model of fiscal feudalism and to those who pressed for reform.

English Excise Taxation

In July 1643, the English Parliament passed the first excise acts in order to raise money to finance the army.2 The king followed suit in December and the Scottish Convention of Estates in February (Engberg, 1966). Very few records of the royalist excise impositions remain, but those that do hint at the desperate state of Charles I’s finances. The royalist schedule of commodities was more extensive than those of Parliament’s original ordinance, and their rates were higher. The royalists desperately needed new sources of funds. John Wandesford, collector for the excise, won his post through his willingness to make loans to the king. The duties themselves were eventually collected by the clerks of the markets or, alternatively, by royalist commanders.3 Although they may well have inspired a proposal in the 1660s for the clerks of markets to collect the excise, no reference to these royalist imposts has been found in contemporary discussions of the excise after the Restoration (BL Add MS 28078, f. 452). Elias Ashmole, king’s commissioner for the excise at Lichfield, was the sole known royalist excise officer to have a career in the excise after the Restoration. Ashmole served Charles II as excise comptroller and audito...