eBook - ePub

Entrepreneurial Icebreakers

Insights and Case Studies from Internationally Successful Central and Eastern European Entrepreneurs

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Entrepreneurial Icebreakers

Insights and Case Studies from Internationally Successful Central and Eastern European Entrepreneurs

About this book

This book presents key insights about the challenges and the approaches they applied. All companies are featured in 15 teachable case studies – ready to use in entrepreneurship and strategy courses – that represent a broad level of diversity with regard to countries, industries, topics, growth phases, challenges and internationalization strategies.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Entrepreneurial Icebreakers by J. Prats,M. Sosna,S. Sysko-Romanczuk,Kenneth A. Loparo,Sylwia Sysko-Roma?czuk in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Entrepreneurship. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Conquering International Markets from Transition Economies

1

Entrepreneurship in Transition Economies

When Ivo Boscarol, CEO of Pipistrel – a light aircraft manufacturer from Slovenia – started his company, it was unimaginable for private persons in Yugoslavia to own their own aircraft, let alone their own aircraft manufacturing facility. If ultralight pilots wanted to fly, they had to do it covertly. They had to wait until the sports and army pilots finished flying for the day, then sneak in an hour or two of flying before darkness fell. As they flew late in the evening, using aircraft lights with triangular hang-glider wings, the local people jokingly referred to them as “bats” – in Latin, Pipistrellus.

Ivo’s first business was printing. He also had a passion for photography and even managed some rock bands. The photography helped him pay his way through college, though he got so busy with his businesses that he never graduated with the economics degree he had set out for.

At that time he had also developed an interest in flying. However, during the late 1980’s, it was difficult to fly an aircraft freely in the totalitarian regime of Yugoslavia, as the military controlled the movement of all aircraft. Ivo had a desire to fly when and where he wanted. On a visit to Italy, he saw a motorized hang glider and decided then and there that he was going to own and fly his own aircraft. Ivo knew it was difficult, if not impossible, to bring the glider into the country in one piece, as it was not legal to own your own ultralight aircraft at the time. He purchased it anyway and imported it into Yugoslavia in bits and pieces, disguised as parts for something other than an aircraft. When he finally had it all and put it together, he wasn’t satisfied with the construction. His conclusion was that it not only looked dangerous – it was made of aluminum and wire, with fabric wings and a small engine at the rear – but it was dangerous.

Ivo first modified his own glider to make it more robust and later those of other pilots who approached him. Eventually, the Italian company he had purchased the glider from contacted him and wanted Ivo to make the same modifications to their aircraft. Normally, modifications to an aircraft were not permitted without permits and drawings approved by federal aviation bodies which also require significant associated design drawings and so on, all of which must be carried out by a licensed aircraft maintenance engineer (LAME). As he spent more and more time modifying gliders he decided to build one of his own.

Ivo approached the country’s aviation authority to get the required permits and approvals to build and sell ultralight aircraft, as they were technically not permitted in Yugoslavia. He was received with a great deal of laughter because no one believed that a private individual would try to build an aircraft in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Furthermore, what kept the aviation department bewildered was that he wanted to build an ultralight aircraft – something nobody in the aviation department knew anything about as they were mostly managed by the military. The aviation department contacted a Slovenian state-owned aircraft manufacturer and asked if they knew anyone who could help them deal with the case, someone who was known as an expert in the field. They were given the name of Ivo Boscarol.

After many meetings, they gave Ivo approval. The problem, however, was that there were no systems, exams or regulations for those who wanted to manufacture their own ultralight aircraft. Ivo took this opportunity to write the exam – the same exam that he himself was required to pass to get approval to manufacture his aircraft. He subsequently wrote many of the regulations and requirements for manufacturing ultralight aircraft in his country. Ivo became the first totally private aircraft manufacturer in the former Yugoslavia – and went on to write additional chapters of aviation history.

Source: CASE 11: Pipistrel: The Freedom of Flight; p. 290

This book is about successful companies from Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) and Russia; about entrepreneurs, like Ivo, who not only defied the odds at home but also managed to build a global presence and reputation for their enterprises. We call them Entrepreneurial Icebreakers. We shed new light on how these entrepreneurs created value in less-friendly environments – for themselves as well as others. Our findings can enrich global and especially transitional entrepreneurship practice and research. We hope that prospective entrepreneurs will be encouraged to pursue and realize their ideas and are not stopped by the perception that it is an “impossible dream” when starting a company in a context that seems to put one on the downside of advantage. We also wish that professors and other players and organizations in the entrepreneurship-related ecosystem will benefit from the insights in this book and the materials we provide in order to improve business and entrepreneurship education.

When the context is not conducive to entrepreneurship

The rise of entrepreneurship throughout post-Soviet countries has fundamentally transformed their economies. Since the mid-1990s, the private sector share of GDP was constantly increasing, but did not have the same percentage of the national economy in all transition countries. It was, for example, approximately 80% in Hungary, 75% in the Slovak Republic and even 70% in the Russian Federation, but 20% in Belarus, 35% in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and 45% in Moldova (EBRD 1999). Private sector value added included income generated by the activity of privately registered companies as well as by private entities engaged in informal activity (EBRD 1999). A lot of research and reports were done to increase knowledge about the wealth-creation phenomena throughout post-Soviet transition economies. Such works explain how various countries adapted to the market economy and the political environments that enabled development. However, not much attention has been devoted to understanding how entrepreneurs from Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) have gone from lag to lead markets and have attained top positions in their respective industries.

In the first years of the 1990s, many CEE governments saw the transition to a market economy simply as a shift in the ratio of public to private businesses. Of the two routes to a private sector – privatizing existing firms and creating new ones – the policy debates focused almost exclusively on the first. Governments were concentrated on privatizing public enterprises which were struggling with new market rules, threatened with bankruptcy and at risk of creating social unrest among their thousands of employees. Everything worked against entrepreneurs at that time. Little attention was given to how reform policies could stimulate the creation and sustainability of new businesses. Indeed, the existing environment was hostile to new business creation. State-owned firms, fearing competition, harassed new entities and corrupt bureaucrats extorted bribes. Additionally, CEE markets lacked stable institutional frameworks. Entrepreneurs could not rely on courts to enforce their contracts. Bank loans were unobtainable by most and there was little legal or regulatory provision for shareholding. Issues like legal and employment restrictions made new business opportunities difficult to pursue and exploit (Johnson et al. 2002a). Still, about 5% of the adult working population of CEE countries attempted to start new firms or became self-employed.1 They did this despite having little protection of private property rights and worse starting circumstances than state companies (Peng 2001).

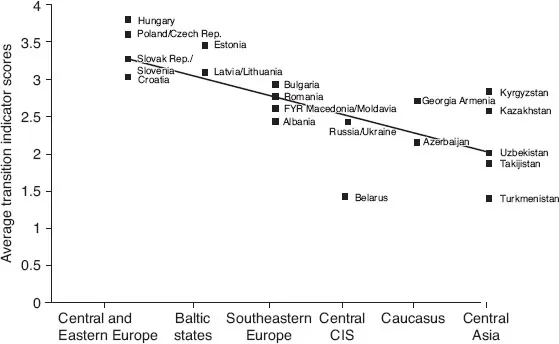

The centrally planned economy was built around state orders, state ownership of production, administered prices and a monobank system. This infrastructure was created to serve large, state-owned firms that produced few consumer goods. Small- and medium-sized firms were almost nonexistent. Trade and services were also a much smaller part of the communist economies than what was typical for a market economy. Privatization and liberalization reforms led to flexibility in prices, wages and production decisions, creating opportunities for potential entrepreneurs. Over the years, there was some evidence of an increasing clustering of countries within each geographical region according to their average scores on the transition indicators, as well as increasing similarities in the patterns of reform across the regions (see Figure I.1.1).

Considerable variation was seen in the macroeconomic indicators. The countries of Central Europe and the Baltic states registered moderate-to-strong growth (at an average annual rate of 4.5% since the mid-1990s). In Southeastern Europe (Bulgaria, Moldova and Romania), GDP contracted sharply. In the Central CIS, GDP continued to contract in Russia and Ukraine, but grew significantly in Belarus. Strong growth was recorded in Caucasus and Kyrgyzstan (see Appendix 2: Growth in Real GDP in Central and Eastern Europe, the Baltic States and the CIS).

Although there was a range of structural, political and geographical factors that distinguished the transition economies from one another, we focus on those that were of great importance to enhancing the entrepreneurial context: property rights’ guarantees, efficiency of formal and informal institutions that support market economy development, access to external financing (capital markets), a cultural dimension related to entrepreneurs’ perception in society, and human capital development.

Figure I.1.1 Regional reform patterns

Source: “Transition Report 1999: Ten Years of Transition” (November 1999), EBRD, p. 27.

Weak property rights and institutional framework

The essential responsibilities of the state in a market economy are maintenance of macroeconomic stability and law and order, including basic property rights. Some transitional governments actively discouraged entrepreneurship by weakening property rights. The right to use an asset and transfer its ownership freely was and still is a “sine qua non condition” for developing entrepreneurial activity. Experience has shown that, where property rights are relatively strong, firms reinvest their profits; where they are relatively weak, entrepreneurs do not want to invest from retained earnings. Research confirms that less secure property rights are correlated with lower aggregate investment and slower economic growth (Johnson et al. 2002b). In the first decade of the transition period of post-Soviet countries, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- Part I Conquering International Markets from Transition Economies

- Part II Case Studies of Internationally Successful CEE Companies

- References

- Index