- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The book analyzes how the administrations of Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush, Bill Clinton, and George W. Bush used force in response to incidents of international terrorism - providing comparison between each of the administrations as they grappled with the evolving nature and role of terrorism in the United States and abroad.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Presidential Policies on Terrorism by D. Starr-Deelen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & European Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

One of the most enduring expressions from George W. Bush’s administration was the claim (or a variant) that “everything changed on September 11, 2001.” As most people on the planet watched on TV that day, 19 hijackers in four hijacked planes shocked the world by flying into the World Trade Center, the Pentagon, and a field in Pennsylvania. The final death toll was almost 3,000 with thousands more injured and the United States traumatized (Duffy, 2005:1).

The terrorist attacks were attributed to Osama bin Laden and the al Qaeda network that was blamed for previous attacks on American embassies in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam in 1998 and the USS Cole in 2000. A noted American expert on terrorism wrote that “bin Laden himself has re-written the history of both terrorism and probably of the post–Cold War era—which he arguably single-handedly ended on September 11th” (Hoffman, 2001:4).

The terrorist attacks in the United States had a profound effect on how Americans and the American government viewed terrorism and counterterrorism. After the attacks, the Bush administration began a “war on terror” that emphasized the use of military methods in combating international terrorism. As a result of the attacks, the United States removed the Taliban regime in Afghanistan late in 2001 because of its support for Osama bin Laden and the al Qaeda network. The Bush administration also articulated a doctrine of “pre-emptive self-defense” in its National Security Strategy, which permitted the United States to strike militarily at any state that threatened its security before the country became the victim of an armed attack.

In March of 2003, the administration of George W. Bush led an invasion of Iraq, which eventually toppled the regime of Saddam Hussein and led to his capture. This invasion was justified as a part of the “war on terror,” even though there is currently no evidence that Saddam Hussein was involved in the attacks of September 11. While the US-led military action in Afghanistan was largely accepted by the world community as legitimate, the legality of the invasion of Iraq remains hotly disputed. Also, the quality of the intelligence that was used to advocate invading Iraq remains controversial.

The dramatic events of the second Bush administration (reaction to the 9/11 attacks, “war on terror”, invasion of Iraq, establishment of Guantanamo) often appeared to be drastic departures from earlier administrations, particularly the preceding administration of Bill Clinton. This research closely examined how different the second Bush administration was, and explored the constraints on presidents in their foreign policy decision making as it pertains to using force against international terrorism. In particular, the roles of the American legislature, the Congress, and the judiciary were analyzed to determine whether balanced institutional decision making was evident regarding decisions to use force in counterterrorism operations.

There is a special dynamic at work regarding the expansion of executive branch powers and terrorism that was not unique to the Bush II administration. Not only is the executive more likely to grab power in its counterterrorism operations, the other branches of government are most likely to acquiescence to the power grab. The evidence indicates this is due to a combination of several factors: (1) the special dynamic of terrorism in which a frightened public demands action after an attack while accepting government secrecy; (2) lack of congressional incentives and political will to practice effective oversight of the executive when it uses force against international terrorism; and (3) a tendency of American courts to defer to the executive branch regarding national security decisions. Furthermore, if an administration pursues a war instead of a law enforcement approach to the problem of international terrorism, there are more theoretical constraints on executive branch action than real constraints.

A serious examination of the constraints faced by modern American presidents regarding their foreign policy decisions on the use of force in counterterrorism indicates that there are fewer constraints than one assumes. In this regard, the notion of an “imperial president,” where presidential power is not adequately balanced by the other branches of government at the expense of presidential accountability, forms an essential part of the analysis. The approach and underlying assumptions of Schlesinger’s concept of the imperial president underlie the use of force by the past four administrations. (Schlesinger, 2004) A pattern of “executive initiative, congressional acquiescence, and judicial tolerance” regarding presidential actions in foreign affairs emerges (Koh, 1990: 5). Finally, the common themes and norms of behavior among the administrations reviewed suggest what the Obama administration might do if faced with responding to a major “armed attack” by terrorists.

An examination of the administrations indicates that a confluence of factors, involving terrorism, the balance of power among the world’s strongest states, and domestic political realities, shaped various presidents’ decisions to resort to force against terrorism. In addition, the threat posed by international terrorism changed during the course of the administrations from state-sponsored to non-state terrorism with resulting repercussions and policies. At the same time, the Cold War ended with the dissolution of the Soviet Union, which eliminated the superpower rivalry and encouraged a more multipolar world. Despite the pledge of a “new world order” in the early 1990s, the United States retained its nuclear arsenal, a large standing army, and the capacity to project its armed forces around the globe. The basic rules allocating the power to deploy force in the American system of government were written at the Constitutional Convention in 1787, under vastly different circumstances. The evidence since 1980 suggests that these factors encourage an executive more imperial and unfettered than constrained and accountable when using force to prevent and respond to international terrorism.

This book questions whether the claim that “everything changed on 9/11” applies to the use of force by American administrations to combat international terrorism. Specifically, it explores whether the administration of George W. Bush was significantly different from the previous three administrations regarding decisions to use force. It also examines the current Obama administration and its uses of force, especially the use of armed drones. Several concepts need to be defined and discussed before detailing the five administrations. For instance, what is meant by the term “terrorism”? How has international terrorism changed from the administration of Ronald Reagan to that of Barack Obama? The first chapter addresses these questions and the international legal norms regarding the use of force.

At first blush, claiming that one extremely spectacular terrorist attack by non-state actors “changed everything” appears like an exaggeration. It seems improbable that 19 hijackers with four planes could seriously damage the international legal regime that the United States, the United Kingdom and other countries laboriously built after WWII to restrain the resort to force. Perhaps the more accurate claim is that the Bush administration’s reaction to the terrorist attack of 9/11, that is, the use of military force against the regimes in Afghanistan and Iraq and the doctrine of pre-emption, changed everything.

My interest in writing a book on terrorism and the use of force under international law came about as a result of living near Washington, DC, on 9/11 and experiencing the changes in tone, if not substance, that occurred in the Bush administration’s post-9/11 foreign and domestic policies. I noted that “everything changed on 9/11” was used as an excuse for pursuing all types of questionable policies, and accusing someone of a “pre-September 11th” mind-set was as effective as calling him/her a communist in the 1950s for closing down political debate. The climate of fear that pervaded Washington, DC, on September 11, 2001, continued in the autumn of 2001 and extended into 2002 and 2003 and beyond as the public grappled with al Qaeda, the anthrax attacks, sniper assaults, and various terrorism scares that unnerved people and may have unwittingly facilitated the Bush II administration’s plans for a “war on terror.” The Bush administration’s links between al Qaeda and Saddam Hussein prior to the Iraq war in 2003 were troubling, and the uncertain nature of compelling constraints on the administration was unsettling. Due to my background in international law, it seemed natural to evaluate the status of the norms governing the use of force and what constrained American presidents regarding the use of force.

Interviews

One problem I encountered in conducting interviews on the topic of counterterrorism was the unwillingness of former members of the Bush II administration to disccuss the administration’s “war on terror” with me. Due to the partisan atmosphere that prevails in Washington, it was difficult to get anyone to discuss the administration’s policies. However, I was able to interview Colin Powell’s former chief of staff, Lawrence Wilkerson, and two former members of the CIA. The following people were interviewed for this research:

•Peter Bergen: National Security analyst and author of several books on Osama bin Laden and al Qaeda.

•Louis Fisher: Former senior specialist on Separation of Powers, Congressional Research Service, and author of many books on constitutional government including The Constitution and 9/11: Recurring Threats to America’s Freedoms.

•Interviewee A: Former CIA analyst who worked at the CIA for 21 years; she was in the Counterterrorism Center (CTC) at the CIA during the end of the Clinton administration and for the first three years of the Bush II administration.

•Paul Pillar: Former deputy chief of the CTC at the CIA and author of Terrorism and U.S. Foreign Policy.

•Lawrence Wilkerson: Former chief of staff to Secretary of State Colin Powell from 2002 to 2005.

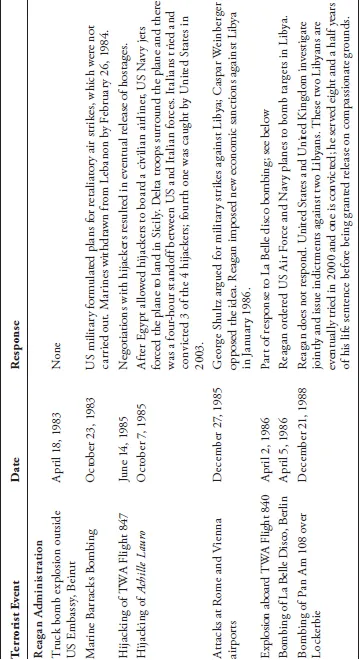

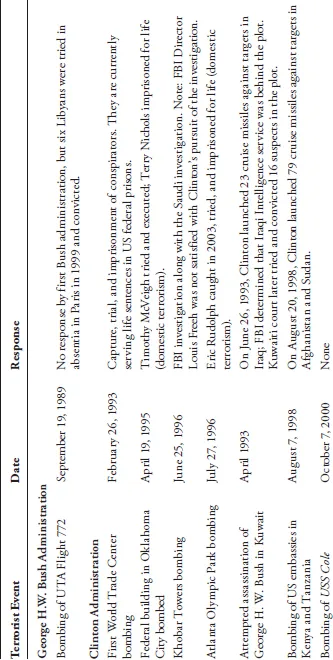

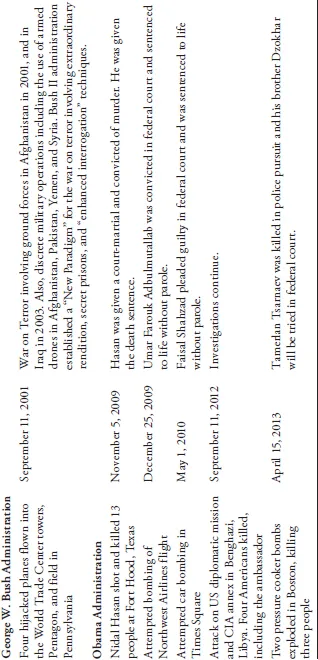

Table 1.1 illustrates the most significant events, dates, and responses during the five administrations.

Table 1.1 Major Terrorist Events from Reagan to Obama

Terrorism Defined

One particular challenge of this book is the subject matter of terrorism; there is no one generally agreed upon definition of terrorism and, in fact, the UN Special Rapporteur on Terrorism and Human Rights noted that 109 definitions were put forward between 1936 and 1981. Many commentators, lawyers, and states have struggled for a common definition when negotiating international treaties, but it remains elusive, mainly due to the oft-stated proposition that “one man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter.” In addition, there are many variants of terrorism including terrorism by the state, state-sponsored terrorism, religious terrorism, revolutionary terrorism, and transnational terrorism, to name but a few categories (Townsend, 2002). The focus in these chapters is on non-state terrorism and the particular reactions of various administrations to acts committed by sub-state agents against the United States. Therefore, cases of state terrorism where the state engages in terror for internal control or repression, or for external aggression, are by definition not part of this analysis.

My book will not explore the many types of terrorism or attempt any social, political, or economic explanation for its occurrence. The notion of “catastrophic” terrorism involving weapons of mass destruction (WMD) and high levels of casualties became common in academic literature written after 9/11. To the extent that WMD’s are discussed, it is in the context of the Bush administration’s rationale for invading Iraq in 2003. The focus will be on international, not domestic, terrorism and the definition used in this work is “premeditated, politically-motivated violence perpetrated against non- combatant targets by sub national groups or clandestine state agents, normally intended to influence an audience” (Reich, 1998:262). The most relevant elements of that definition for this research are twofold: the use of violence for political ends, with the agents using the violence being non-state entities.

Another challenge posed by the subject matter is the fact that terrorism as a tactic is not static. Indeed, international terrorism changed significantly from Ronald Reagan’s administration in the 1980s when the focus was on state-sponsored terrorism to the Islamic fundamentalist terrorism that dominated the Bush II administration and remains the focal point of the Obama administration. Later chapters trace the changing nature of the terrorist threat faced by the administrations.

The Crime versus War Dichotomy

Scholars and national security experts have written a great deal about the merits of different methods of preventing terrorism and responding to specific acts of terrorism. According to one analyst, the United States has employed different tools since WWII to combat international terrorism, including international legal conventions outlawing specific acts, defensive measures, addressing the causes of terrorism, articulating a policy of no concessions, economic sanctions, prosecution of perpetrators, preemption, disruption, and the use of military retaliation (Tucker, 1997: 72). This book focuses on the use of force from 1980 to the present because, in addition to being controversial, it illustrates one area of foreign policy making where the president encounters few real constraints imposed by the other branches of government.

Broadly speaking, there are two schools of thought or models regarding modern approaches to combating international terrorism by liberal democracies. These are not merely descriptive, but “provide moral frameworks for judging the actions of governments and determining what the law should be” (Finkelstein, Ohlin, and Altman, 2012: 5). The first approach is to categorize international terrorism as not “merely” criminal activity, but as a national security threat that imperils the very existence of the state. According to this view, international terrorism is more like war, with its signature violence and indiscriminate killing, than a crime, where the primary motive is often economic gain. This is also known as the armed-conflict model as it categorizes terrorists as enemy combatants who intentionally target civilians while fighting without distinguishing themselves from civilians. Moreover, according to this model, terrorists violate the laws of war and, if captured, “it is morally and legally permissible to try them in military courts and accord them a less rigorous form of due process than is found in civilian criminal courts” (Finkelstein, Ohlin, and Altman, 2012: 6). However, there is no legal obligation to try to capture terrorists; it is lawful to direct lethal force against them, just as any country at war targets the enemy’s fighters. Terrorists represent a grave national security threat, so the use of military force against them to protect the nation is warranted.

The war or armed-conflict model posits that treating terrorism as a crime ignores its fundamental nature and results in ineffective counterterrorism measures because “proactive” measures, necessary to protect the institutions of the state and retain public confidence in the government, are precluded. Long before the second Bush administration used military force in response to the 9/11 attacks, some members of the Reagan administration, including George Shultz (secretary of state from 1982 to 1989), advocated proactive measures against state sponsors of terrorism involving the preemptive use of military force. Another advocate of proactive measures, Abraham Sofaer, legal advisor to the Department of State from 1985 to 1990, was critical of UN efforts to agree on international methods to reduce terrorism. In an article in Foreign Affairs Sofaer wrote, “International law has been systematically and intentionally fashioned to give special treatment to, or to leave unregulated, those activities that cause and are the source of most acts of international terror” (Sofaer, 1986: 922). Sofaer and Shultz foreshadowed proponents of “going on the offense” against terrorism in the second Bush administration when they advocated an “active defense” against terrorism, arguing that the United States could lawfully use force to prevent, preempt, and deter further attacks.

After the 9/11 attacks, Sofaer, now at the Hoover Institution, supported the Bush II administration’s embrace of the concept of preventive action with the “objective of preventing terrorist threats before they are realized—rather than primarily treating terrorism as a crime warranting punishment after the fact” (Sofaer, 2010b:109). He criticized the UN Charter rules on the use of force as inadequate in light of modern realities and non-state actors because, in Sofaer’s view, these rules “effectively protect terrorists, proliferators, and irresponsible states” (Sofaer, 2010b:111). His solution was to propose a set of “guidelines” that, while not strictly lawful under UN Charter rules, remain true to the Charter’s purposes of maintaining peace and security. Under Sofaer’s guidelines on the use of preventive force, a state could use force against non-state actors in a foreign state without permission to prevent a terrorist attack even if there is no UN authorization as long as the use of force complies with the overall purposes of the UN Charter.

The other school of thought or model, frequently known as the law enforcement model as it treats terrorism as a criminal act, is represented by academics like Paul Wilkinson. Proponents of the law enforcement model contend that terrorism should be handled like any other serious crime; police,...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Principles Allocating Foreign Affairs Powers

- 3 The Administration of Ronald Reagan

- 4 The Administration of George H. W. Bush

- 5 The Administration of Bill Clinton

- 6 The Administration of George W. Bush

- 7 The Obama Administration and the War on Terror

- 8 The Legacy of the War on Terror

- Appendix 1: UN Charter

- Bibliography

- Index