eBook - ePub

Social Education for Peace

Foundations, Teaching, and Curriculum for Visionary Learning

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Carter illuminates and validates the vital role of visioning in social education. The book features peace in social education with instructional recommendations, planning resources and descriptions of transdisciplinary learning. It elaborates mindful citizenship across social, environmental, ethical, geographic, economic and political realms.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Social Education for Peace by C. Carter in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education Curricula. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Foundations of Social Education for Peace

Abstract: Notions of peace and how people accomplish it have existed worldwide, for millennia. The precursor to the accomplishments was envisioning peace. While principles of spiritual and indigenous traditions provided signposts for paths to peace, harmful responses to conflict also stimulated peace efforts. Eastern philosophies and Western ideologies offer the connected world a solid foundation for building peace in all regions. Students can learn global peace concepts and develop visioning skills in each of the subject areas. This chapter identifies other capability goals in peace education as well as domains of conflict transformation and provides a case example of students’ peace dramas.

Carter, Candice C. Social Education for Peace: Foundations, Teaching, and Curriculum for Visionary Learning. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015. DOI: 10.1057/9781137534057.0005.

Theoretical foundations

Forming the foundation of social education for peace are notions that spanned millennia as well as recent ones in the past two centuries. There are multiple ideas about how people might live together in a condition of peace. Modern peace education was constructed with such conceptions and research that analyzed their implementation. Teachers have incorporated as curriculum the conflicts in their society and world. Their motivation for active response to societal and students’ needs is a crucial component of visionary education as well as peace-oriented citizenship. Proactive people who address conflict apply theories that are foundations of social education and peace development (Carter & Kumar, 2010; Diamond, 2000; Nagler, 2004). The prosocial stance of peace educators and peacemakers has foundational ideas about how a society could improve its situation, especially through the avoidance of violence. The term prosocial refers to an orientation that may be evident in dispositions or skills known for supporting improvement of society. The motivation for prosocial modeling comes from a desire for improvement of circumstances where harmful responses to conflict exist. Envisioning other types of responses is the crucial work of educators and their students on the ideological paths that peacemakers have made.

Throughout the world, people have envisioned peace and then taken action with the use and augmentation of existing ideas. People who pursued peace have also advanced new ideas. Many of their accomplishments, which peace history documents, occurred after they pictured better situations than the ones they observed or knew about (Curti, 1985). Ian Harris (2008) explains how wars in Europe and then a world war stimulated the formation of peace societies whose members called for education to prevent war. Organizations that held visions of life without violence, like the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, are peace societies. While a disposition toward social responsibility or stewardship was evident in the minds of many proactive people during the past century, professors, teachers, and mentors motivated others. Informing about notions of and goals for societal and personal improvement have been important lessons that teachers, as well as community and family elders, sages, and spiritual leaders, provided. Conceptions of a good society have been germane while ideas about how to bring about “the good” have varied. These variations exist as diverse ideas and means for maintaining a good society (Bellah et al., 1991; Dajani, 2006). They are worthwhile considerations for students acquiring visionary social education in a multicultural world (Mills, 1997).

Principles across spiritual traditions

Principles are the ethical standards in a society that have held people socially, and sometimes legally, accountable. They serve as guideposts of right action for the well-being of the society or the culture that maintains the principles as ideological and behavioral codes, if not membership criteria. Principles traditionally provided by scriptures promote envisioning. For example, Proverbs 29:18 of the Bible states, “Where there is not vision, people perish . . . ” (Bible Study Tools, August 4, 2013, para. 1). Principled living that sustains a society occurs through picturing how that way of life can occur. Consequently, each society has had a foundation of clarified principles that enabled peaceful interaction between its members. The book Spirituality, Religion, and Peace Education (Brantmeier, Lin, & Miller, 2010) provides in-depth descriptions of how the principles served as the foundation of learning and guidelines for peace in many world regions.

It is important to acquire knowledge about principles that support unity across cultures and regions. The principles of a culture offer visions of and standards for a good life. For example, many cultures have edicts to sustain and preserve human life. A comparison of principles in various religions reveals the commonality of people in different cultures. People desire a life in the condition of peace. When viewing differences of surface culture as interesting rather than objectionable, comprehension of deep commonalities across cultures supports a disposition of acceptance. Modeling by adults of acceptance when they encounter cultural differences facilitates this disposition development by youth who see that behavior. In other words, cultivation of acceptance happens during observation of that enacted disposition as well as in demonstrations of curiosity about cultural differences (Pate, 1997). The principle of unity within a culture is evident worldwide. There is unity in diversity across cultures as well as within one society. Diversity of thoughts and skills has been crucial for survival, especially in the face of conflict. Experts in conflict resolution and transformation have identified how helpful it is to have different perspectives of a problem included in the work for its solution (Lederach, 2003). A component of indigenous peace as well as current conflict work by specialists in problem solving is the ideology of unity. The notion of unity orients humans toward cooperation and interdependence as a community of life forms.

Indigenous concepts

Indigenous concepts of peace have existed throughout the world. Enduring concepts of peace in the daily living of indigenous people influence their avoidance of and solutions for problems (Odora Hoppers, 2002; Ramose, 1996). For example, the African concept of e Munthu (Malawian language) that translates as “humanness” expresses a notion of fraternity in a community. To be fully human, one must interact well with others, thereby demonstrating ethical responsibility (Sharra, 2006).

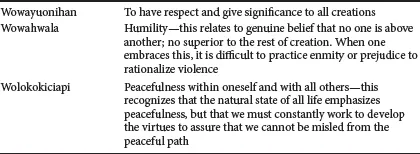

From the Indigenous Peoples of North America, we have similar viewpoints, illustrated by examples in Table 1.1 from the Lakota People (Four Arrows, 2010, p. 137).

The laws known as the Great Peace, which the Iroquois Confederacy has maintained for many centuries, articulate the responsibilities of individuals and groups within and across communities to maintain ethical interactions. Included in the laws of the Iroquois are notions of conflict management and dispute resolution with a future orientation. For example, Law 26 calls on political leaders to serve as mentors and spiritual guides with use of the following statement.

Hearken, that peace may continue unto future days!

Always listen to the words of the Great Creator, for he has spoken.

United people, let not evil find lodging in your minds.

For the Great Creator has spoken and the cause of Peace shall not become old.

(Murphy & National Public Telecomputing Network, 2012)

TABLE 1.1 Lakota principles

Incorporated into the Aboriginal worldview, with the notion of the “Dreaming” that preceded all creation, is vision. As envisioned in the Dream, peace results from compliance with “the law” that embodies the rules for living well in the created world (Tonkinson, 2004). Modes of living to manifest the Dream vary across regions and cultures. Diversity in pursuit of peaceful lives is normal and interesting to learn about in oral and written accounts (Mathis, 2001).

Literature about the pursuit of peace in traditional societies reveals people have had similar notions and processes of peacemaking, although there are differences in particular norms. One common strand has been methods for peaceful communication and exchange across cultures. With differences in values and norms that distinguish cultures, careful social interaction can maintain optimal relations between groups. Balance and mutuality necessitate good relations across as well as within groups (MacGinty, 2008).

Strands of indigenous peacemaking that have recently been adapted into modern society are restoration of relations through compensation for losses, honoring the harmed, and other processes (Carter, 2010b). For example, modern peace initiatives incorporated from indigenous practices include Circles for communication about harm and restoration of well-being. A Circle is a process in which people meet for communication together. Participation in a Circle by all affected people enables sharing of perspectives while it can convey interest in addressing the needs that the harmful act evidenced, in addition to the outcomes of the harm. Schools as well as other community organizations now use Circles for problem solving with a future orientation (Pranis, 2005). With an orientation toward restoration of peace, schools have been unknowingly following in the footsteps of indigenous peoples by taking steps to restore damaged relationships and develop new ones that improve social interactions in the learning environment (Amstutz & Mullet, 2005; Cavanagh, 2009). Faith groups around the world adapted restorative practices of First Nations, long before education became secularized. In The Spiritual Roots of Restorative Justice (Hadley, 2001), the contributors of each chapter identify how restoration has been occurring in many spiritual as well as religious traditions. The book identifies these enduring practices as expressions of human hope that have been evident in a multitude of faiths and regions. Awareness of the worldwide notions of peace and paths to it that people have taken throughout human history, across religious and spiritual traditions, builds understanding of human commonality in the desire for peace. To counteract cultural polarities that are evident in discourse about conflicts between groups, educators emphasize how people in each group have used their own culture’s notions of peace in response to violent conflict.

Eastern philosophies

In the Eastern Hemisphere, visions of peace became enduring philosophical and spiritual traditions that Westerners have adopted. For example, a notion that educators as well as many others have fused in their responses to conflict, if not their daily practices, is the Tao (the Way). The Way involves simple and harmonious living with people and all of nature. In the Tao of Teaching (1998), Greta Nagel shares through stories about teaching in the USA how the Tao influenced personal as well as professional actions, and non-actions, that have a peace orientation. For example, she applies the goal of balance that yin and yang represent. Methods to pursue the Way are balance of gender representation in the curriculum and classroom interaction as well as teacher and student talk time. Additionally, balancing one’s work and relaxation time enhances one’s ability to benefit others, due to increased personal contentment. Another facet of Taoism is facilitation of harmony. The ideal is human balance with nature as well as with other people, especially in the fulfillment of life-sustaining needs. The modern ecological movement resonates with reverence for nature in pursuit of the Tao. Other philosophical traditions also express the notion of balance and harmony.

Buddhism promotes the idea of the Middle Way, which is a path of moderation that avoids extremes, such as destructive behaviors with the self and others (Yeh, 2006). Nirvana, which translates to enlightenment, derives from the elimination of dualities that obscure progress on the path to peace. Justification of destruction is an outcome of a dualistic viewpoint that rationalizes harm. Principles of Jainism and Buddhism recognize harm of anything as harm to everything. The Sanskrit term ahimsa, which is a life principle for Jains and Buddhists, refers to doing no harm, or nonviolence. In lessons about life choices of Mohandas Gandhi and the founder of Buddhism, Siddhartha Gautama, teachers can provide examples of living in accordance with these notions. For example, the organization Soka Gakkai International applies the principles of Buddhism in current educational and cultural activities. Students learn how Gautama, known as Buddha, eschewed the material well-being he inherited. This facilitated his enlightenment and a way of life that benefited others who were suffering, especially from poverty. In their study of Gandhi, known as the Mahatma (“Great Soul” in Sanskrit), Martin Luther King Jr., who adopted the Mahatma’s strategies, and Nelson Mandela, who applied them in South Africa, students learn how nonviolent action brought about needed change where social injustice existed. The notion of satyagraha, or insistence for truth, was a foundational principle of visionary political actions in response to injustice. With truth (satya) and firmness (agraha), major efforts to eliminate oppression continue to be successful in bringing about envisioned changes throughout the world. Instead of passive resistance that Westerners, such as the female suffragettes, used to bring about political changes, those who embraced satyagraha engaged in activities that prompted oppositional responses. The attention...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- 1 Foundations of Social Education for Peace

- 2 Peace-Focused Policy for Social Education

- 3 Responsive Curriculum and Instruction

- 4 Transdisciplinary and Powerful Learning

- 5 Mindful and Engaged Citizenship

- Appendix: Standards for Peace Education

- References

- Name Index

- Subject Index