eBook - ePub

A 'Macro-regional' Europe in the Making

Theoretical Approaches and Empirical Evidence

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A 'Macro-regional' Europe in the Making

Theoretical Approaches and Empirical Evidence

About this book

Macro-regional strategies seek to improve the interplay of the EU with existing regimes and institutions, and foster coherence of transnational policies. Drawing on macro-regional governance and Europeanization, this edited volume provides an overview of processes of macro-regionalization in Europe displaying evidence of their significant impact.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A 'Macro-regional' Europe in the Making by Stefan Gänzle, Kristine Kern, Stefan Gänzle,Kristine Kern in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Comparative Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Introduction

1

Macro-regions, ‘Macro-regionalization’ and Macro-regional Strategies in the European Union: Towards a New Form of European Governance?

Stefan Gänzle and Kristine Kern

‘Macro-regionalization’ and the making of the European Union’s ‘macro-regional’ strategies

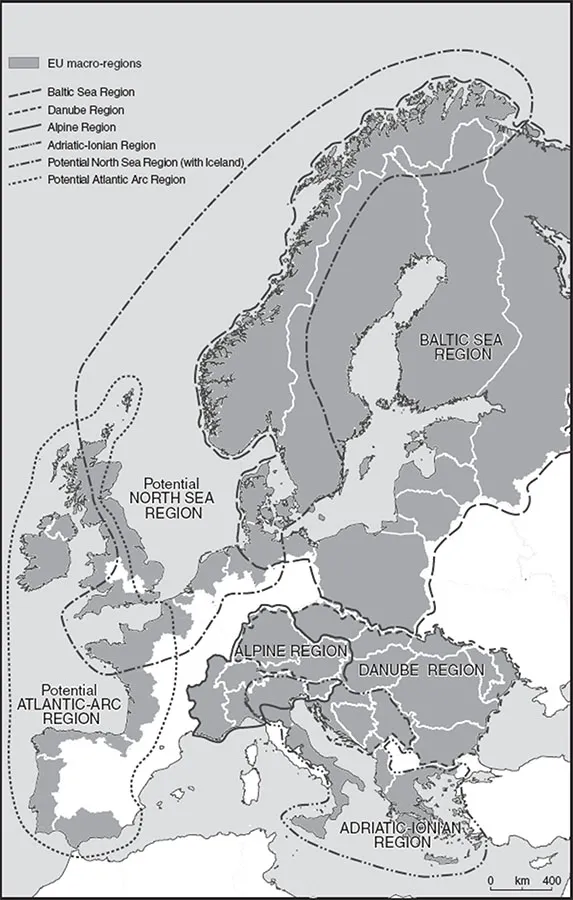

With the adoption of its first ‘macro-regional’ strategy in 2009 – the EU Strategy for the Baltic Sea Region (EUSBSR) – the European Union has started to charter new territory in transnational cooperation and cohesion policy. Subsequently, other ‘macro-regions’ have begun to self-identify – such as the Danube (2011), the Adriatic–Ionian basin (2014), the Alpine (2015) and the North Sea regions1 (see European Parliament, 2015) – and are in the process of developing similar strategies of their own, often drawing on ‘the inspiration from the EU Strategy for the Baltic Sea Region and the Danube Region’ (North Sea Commission, 2011, p. 2). These developments suggest that some parts of Europe, if not the entire EU, could come to be covered by some kind of macro-regional strategy. Indeed, in 2013, the Lithuanian Presidency of the EU Council proposed a ‘Europe of macro-regions’ (Lithuanian Presidency of the EU Council, 2013, p. 9) and an ever-increasing area has been described as having succumbed to a kind of ‘macro-regional fever’ (Dühr, 2011, p. 3). Such observations and the concrete developments that underpin them warrant a critical assessment of this ‘“nouvelle vogue” of transnational cooperation’ (Cugusi and Stocchiero, 2012), which has also been depicted as a new ‘tool of European integration’ (Dubois et al., 2009, p. 9; see also Bellini and Hilpert, 2013).2

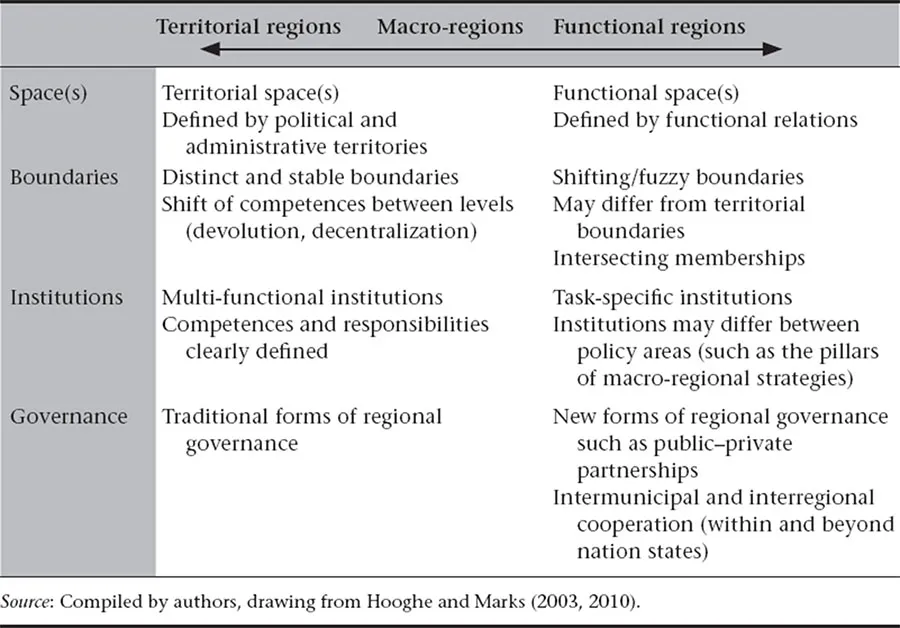

According to a widespread definition first put forth by the then EU Commissioner for Regional Policy, Paweł Samecki, a ‘macro-region’ refers to ‘an area including territory from a number of different countries or regions associated with one or more common features or challenges’ (European Commission, 2009, p. 1, original in bold). Consequently, such regions are socially construed and ‘demarcated’ by ‘flexible, even vague’ boundaries (European Commission, 2009, p. 8; see Table 1.1). This is not to say that historical and cultural commonalities do not matter at all in the formation of such regions, but macro-regions are both ‘imagined’ and ‘manufactured’ by the need for functional cooperation around, for instance, a common regional sea, mountainous area or river system, which ‘transcend[s] all territorial frontiers’ (Forsyth, 1996, p. 29). Turning to the notion of ‘strategy’, it is conceptually useful to maintain that a macro-regional strategy ‘(1) is an integrated framework relating to member states and third countries in the same geographical area; (2) addresses common challenges; (3) benefits from strengthened cooperation for economic, social and territorial cohesion’ (European Commission, 2013a, p. 3). The concept is based on five core principles construed around the need to integrate existing policy frameworks, programmes and financial instruments; to coordinate between sectorial policies, actors or different tiers of government; to cooperate between countries and sectors; to involve policymakers at different levels of governance; and to create partnerships between EU member states and non-member countries (see European Commission, 2013a, p. 3). EU macro-regional strategies are neither single-issue focused in terms of policy nor exclusively or primarily limited to the realm of intergovernmental collaboration. Rather, they frame ‘a bigger picture’ and aim at mobilizing existing funding schemes, tapping on the expertise of existing epistemic communities and stakeholders from all tiers of the EU’s multilevel system. EU macro-regional strategies seek to provide a strategic platform or framework of reference for existing actors that would allow them to adjust to the activities of other stakeholders. EU macro-regional strategies refer to the objective of integrating different policy sectors that influence one other, such as land-based versus sea-based sources of pollution. While none of these dimensions are anything new in themselves, their systematic integration in a comprehensive and evolving new governance architecture at the macro-regional level is. We must therefore be drawn to contemplate whether this new development has been successful to date and whether it does or might trigger tangible changes on its macro-regional constituencies. It is the core goal of this edited volume to find an answer to this question.

In the words of the European Commission, macro-regional strategies account for no less than ‘regional building blocks for EU-wide policy, marshalling national approaches into more coherent EU-level implementation’ (European Commission, 2013a, p. 5, emphasis added). These ‘regional building blocks’ aim to foster a genuinely transnational perspective, to draw functional cooperation and territorial cohesion closer together, and to encourage collective action between public and private actors across all levels of EU governance in areas such as transportation, infrastructure, economic development, public health and environmental policy. Macro-regions or subregions are not new phenomena per se. In contrast, hybrid forms of functional–territorial regions or, alternatively, ‘soft spaces’ (Metzger and Schmitt, 2012; Stead, 2011, 2014) that cut across national boundaries of existing political entities have existed before (see Joas et al., 2007). Terms such as ‘macro-’ and ‘meso-regions’ (Christiansen, 1997) have been used before to depict ‘both globally significant groups of nations (the EU, ASEAN etc.) and groupings of administrative regions within a country’ (European Commission, 2009, p. 1), such as, for instance, Romania’s four macroregiune as features of the country’s territorial organization. In short, a macro-region refers to a meso-level bringing together a group of units that are at the same time part of (or related to) a more comprehensive political entity. Yet, macro-regions constitute a novel development in that they seek to systematically enhance European or generally global policies in the functionally defined territory of a macro-region by using existing institutional structures in a comprehensive, coordinated and cross-sectoral way. Building on functional commonalities of a given macro-region, macro-regional strategies aim at minimizing the transaction costs of collective action and provide for better and more effective regulation:

Table 1.1 Macro-regions: hybrids between territorial and functional regions

[F]or most environmental problems the EU is not an optimal regulatory area, being either too large or too small. In a number of cases – for example, the Mediterranean, the Baltic Sea, or the Rhine – the scope of the problem is regional rather than EU-wide, and is best tackled through regional arrangements tailored to the scope of the relevant environmental externality. (Majone, 2014, p. 319)

Because macro-regional strategies come as a rather new addition to the EU Commission’s toolbox of concepts and ideas, they should be approached with due caution and in a critical manner. With this caveat in mind, and with the aim of distinguishing ‘macro-regions’ from previous developments such as those mentioned above, we suggest the concept of macro-regionalization (Gänzle and Kern, 2011, p. 267; Salines, 2010, p. 27), as it allows us to capture dynamics that have not yet resulted in the elaboration of a macro-regional strategy, but which are ultimately comparable. This will allow us to also discuss the cases of the North Sea and the Atlantic Arc regions. Hence, we define macro-regionalization as processes, eventually underwritten by macro-regional strategies and underpinned by a single strategic approach. This approach must aim at the construction of functional and transnational spaces among those (administrative) regions and municipalities at the subnational level of EU member and partner countries that share a sufficient number of issues in common. In contrast to previous attempts at forging territorial cohesion in the EU, macro-regionalization is a much more comprehensive approach across policy sectors, and as an EU-wide process, it can be conceived as a de facto (but not de jure) prototype of territorial differentiation in European integration (see Dyson and Sepos, 2010; Gänzle and Kern, 2011) – at its very early stage, if at all (Figure 1.1).

With respect to the composition and number of countries involved, macro-regional strategies differ quite significantly from each other. The EUSBSR, for instance, targets eight EU member states – Sweden, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany (specifically: Hamburg, Schleswig-Holstein and Mecklenburg-Vorpommern), Latvia, Lithuania, Poland – as well as two ‘partner countries’ in northeastern Europe – Norway and the Russian Federation – and can almost be conceived as an EU internal strategy (see Gänzle and Kern, chapter 6 in this volume), while the EU Strategy for the Danube Region (EUSDR) is far more diverse, exhibiting a strong external focus that covers fourteen countries in total, from the source of the river to its estuary (see Ágh, chapter 7 in this volume). It brings together nine EU member states and five accession, candidate and partner countries of the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) – along with the corresponding subnational authorities thereof.3

Figure 1.1 Overview of European macro-regions

© University of Agder, S. Gänzle

© EuroGeographics for the administrative boundaries Cartography: F. Sielker, University of Erlangen 2015

© EuroGeographics for the administrative boundaries Cartography: F. Sielker, University of Erlangen 2015

Although macro-regions can be traced back to various subregional schemes of intergovernmental cooperation – most of which mushroomed in the 1990s – the EU’s successive enlargements in 2004 and 2007 certainly served as the point of departure for the EU strategies in the Baltic Sea and Danube regions (Ágh, 2010; Beazley, 2007). With the accession of Poland and the three Baltic States in 2004, along with Romania and Bulgaria in 2007, the situation in the Baltic Sea and Danube regions changed fundamentally and increased quite substantially the EU orientation of the countries making up the Baltic Sea and the Danube regions. Although the first steps in initiating a Baltic Sea Strategy were taken by the European Parliament (Antola, 2009, p. 5; Schymik, 2011), the launching of both the Baltic and Danube strategies involved the member states and certain subnational authorities (notably, Baden-Württemberg) playing a pivotal role. The development of the Danube Strategy also indicated a shift of power and influence from the European Parliament to the European Commission, since the Commission facilitated and later actively shaped the process of developing the macro-regions, while pursuing an independent and holistic approach compatible with existing policies.

The emergence of macro-regions in their current form has been prompted by a number of exogenous factors primarily instilled at the EU level, and at the level of the macro-regions themselves. There are several important drivers from the EU level. First, the Treaty of Lisbon’s objective is to achieve territorial cohesion, alongside social and economic cohesion. Hence, Art. 174 of the Treaty on the EU stipulates:

In order to prom...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on Contributors

- List of Abbreviations

- Part I: Introduction

- Part II: Development of EU Macro-regional Strategies

- Part III: Theorizing Macro-regionalization and Macro-regional Strategies in Europe

- Part IV: Governance Architecture and Impact of Macro-regional Strategies in Europe

- Index