- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The City in Urban Poverty

About this book

The contributors respond to the absence of critical debate surrounding the ways in which spaces of the city do not merely contain, but also constitute, urban poverty. The volume explores how the spaces of the city actively produce and reproduce urban poverty.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The City in Urban Poverty by C. Lemanski, C. Marx, C. Lemanski,C. Marx in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Development Economics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Poverty and ‘the City’

Susan Parnell

Introduction

The twenty-first century is the first truly urban epoch. However, the well-circulated graphs that reveal the inexorable urban transition of past and future decades are only part of the story. Accompanying the headline demographic message, that this is an era where urbanisation is the dominant motif, is the reminder that the locus of the twenty-first century has shifted away from Europe and North America. We not only now live in an urban world but also a Southern world, in which Asia and Africa are numerically dominant. As the absolute epicentres of population, cities and towns are the places and spaces that provide the foundations on which contemporary and emerging global systems and values will be built (Miraftab and Kudva, 2014; Roy and Ong, 2011). There are other substantive ways in which, over the next few decades, what happens in and is exported from ‘cities of the South’ will come to dominate our collective lives: cities will have massive impact on natural systems changes; the production, distribution and circulation of goods and services; and the experiences of everyday life, health, culture and politics (McGranahan and Martine, 2014; Parnell and Oldfield, 2014; Revi and Rosenwieg, 2013; Elmquist et al., 2013). For the global majority, life will be shaped by urban conditions and expectations. But for all of its centrality, we do not really understand what constitutes ‘the city’ or how urban form, urban management, urban life and identity interface with the experiences of, or responses to, poverty. For over a decade the ambiguity over how poverty and the city interact has been overlooked, as personalised experiences of poverty in the city have been intellectually and programmatically foregrounded. As we face the post-2015 development challenge, some recalibration is in order.

It is not possible to escape the fact that city in the Global South matters more now than ever before in addressing the perennial issue of poverty. It is this reality that underpinned the push to include an ‘urban’ goal, targets and indicators in the United Nations’ sustainable development goals (Parnell et al., 2014). The demographic and spatial transformation of world populations, not least of which is the massive expansion of the number of people living in poverty in cities (Chen and Ravallion, 2007), raises the question of the intellectual apparatus required in setting out the complex practical and intellectual tasks that lie ahead.

Rather than reiterating the now fairly widespread call for more globally relevant urban theory formation (Watson, 2009; Robinson, 2002), I want to be more specific in my suggestion of a way forward; arguing that to have any resonance at all with the world’s wicked problems, like poverty, alternative research perspectives have to either begin from or engage substantively with ‘the city’ by moving beyond the focus on the individual or micro neighbourhood projects to re-emphasise the materiality of the built form and to explore fundamental urban system reform. The issue of scaling up anti-poverty projects from the neighbourhood scale is a major part of this, but understanding the urban system and the system of cities is more than just expanding micro household- or area-based interventions or even of encouraging national urban strategies or global urban development goals, strategic as those interventions may be.

What has happened over the last decade or so is that the city itself (how it is built, serviced, structured, managed and experienced) has slipped in priority as explanations of urban poverty have placed an increasing emphasis on human agency, livelihood strategies and community mobilisation (Moser, 1998; Rakodi and Lloyd Jones, 2002; Mitlin and Satterthwaite, 2013). The focus on people-centred or bottom-up views of the last two decades are in no way wrong, but the human emphasis has meant that the structural and institutional role of ‘the city’ in shaping the experiences of poverty and the responses to poverty are now relatively poorly understood (Pieterse, 2008). In the face of the boosterish calls to let the poor take more control of their lives, anti-poverty action at the city scale can (sometimes inadvertently) be reduced to oppressive, invasive or post-political technocratic urban management (Swyngedouw, 2007). This, in my view, is an error.

Failure to fully recognise that how cities are structured physically and organisationally impacts directly on the poor is naïve; a Southern corrective is due that brings ‘the city’ back into poverty studies, in the same way that the material and ecological understanding of Northern cities saw a resurgence following the work of Marvin and Graham on splintered urbanism (2001). This is not the cry of a lone wolf: there is thankfully a now burgeoning literature focused on urban infrastructure and poverty (Silver et al., 2013; Jaglan, 2013); on the importance of public spaces for the poor (Kaviraj, 1997); and the enduring specialist areas of urban poverty work that are concerned with sectorial elements of the built environment like sanitation, housing or transport. Within the social development and development planning arenas, however, these poverty workstreams have been largely ignored, or alternatively are brought forward as if in response to community demands for local and national governments to address the imperative of scaling up (Tomlinson, 2014; Mitlin, 2014). Rather than this incremental or reformist position that grows out of a participatory planning view, Harrison (2014) argues that what is actually needed is a more fundamental ontological realignment that allows a re-engagement with the materiality of cities and their planning regimes.

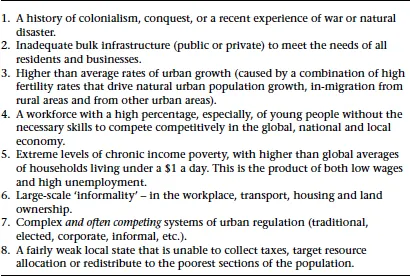

Set against Harrison’s philosophical challenge, the central argument of this chapter is that the nexus of ‘the city’ and ‘poverty’ needs to be reinterrogated from the perspective of the large-scale structural urban realities of the Global South, by which I mean a focus on poverty and the city of the Global South, not just poverty in the city of the Global South. Crudely, this might be described as a top-down rather than bottom-up perspective; more accurately it is a concern with urban systems and urban form, rather than only urban residents or the urban economy. To achieve this objective of rebalancing the modes through which poverty and the city is constructed, the chapter assumes a Southern perspective; that is, one that takes as the urban norm conditions of urban growth, extreme and pervasive poverty as well as large-scale informality and a fairly weak state (Table 1.1). Clearly there is no neat set of ‘Southern urban indicators’, and Table 1.1 does not seek to define such a comprehensive list, but it is included to focus discussion on recognisable and often replicable conditions in cities and countries with extreme rates of poverty that must, because of their (often overlooked) structural consequences, have impact in framing the urban poverty challenge.

In building a Southern view on the city and poverty, I begin by defining ‘the city’ and ‘the city scale,’ clearing the way to construct the argument that because of the vast numbers involved, thinking about the role of the urban in shaping and ameliorating poverty has not been so important since Engels wrote about deprivation and industrialisation in the late nineteenth century, or the early Chicago School writers put the city at the centre of their explanations for black Americans’ disadvantage in the early twentieth century. I then move to reflect critically on the urban poverty research that has current academic and policy currency, demonstrating that the work on urban demography and gender in the city, livelihoods and rights-based analyses made significant advances in understanding urban poverty from the perspective of individuals and communities. Conceptually, however, this emphasis obscures the way poverty is located in the wider workings of the city and does not do justice to the scale of the urban poverty problems outlined in the first section. In seeking alternatives to the micro-scale lived experiences, I revisit important urban poverty work on ‘gender and the city’. Like both Chant and Datu (in this volume) and Moser (2014), I suggest that the older literature on gender included a valuable structural interpretation of urban poverty that has been diluted in recent decades. Reprioritising the more material mode of thinking in the gender and the city writing provides a corrective to inform a framework of ‘poverty and the city’ that gives weight not just to areas of overtly city-scale anti-poverty action, but also to understanding the underlying governmentality, regulatory, natural resource and technical systems that underpin the urban system. Viewed alongside existing knowledge, this more structural, institutional or political economy view provides both an intellectual and political case from which to better understand and advance the fight against urban poverty.

Table 1.1 Potentially distinctive characteristics of ‘Southern cities’ that, individually or collectively, may be significant in assessing poverty profiles, dynamics and responses

What is ‘urban’ poverty?

This chapter rests on the notion that poverty in an urban world is somehow constituted differently from that of a rural world. This is not just an issue of settlement scale, density or function. Moreover, appropriate poverty responses that are grounded in the building and running of the city and which meet basic needs as perceived by urban citizens are essential if global sustainable development goals (SDGs) are to be met and if the globally unacceptably high levels and rates of poverty are to be pushed back. For individual cities, accepting that there is a great deal that can and must be achieved at the sub-national or city scale, puts the political focus of anti-poverty action on actors both within and outside of national government.

Describing the ways that urban poverty is distinct from national rates of deprivation is not simple. Scholars like Moser (1998) and Gilbert (2002) have helpfully and clearly expressed how, in the absence of subsistence livelihoods and access to land, cash or assets become the means for securing rent, transport and food in the city – making income a poor basis of urban-rural comparisons. Mitlin and Satterthwaithe (2013) moreover provide an authoritative account of why urban poverty is consistently underestimated and misrepresented because the specificities of cities (crucially, the dominance of cash-based economies and high levels of inequality) are overlooked. Emphasising the central role of cash in the city has its own dangers and much of the influential new work on urban poverty data, including efforts to move beyond GDP measures, seek to quantify non-subsistence and extra-income variables that determine well-being for urban contexts (c.f. Kanbur, 1987; Kubiszewski et al., 2013). Acknowledging the differential characteristics and measurements of urban poverty in this way is a start to rethinking the city/poverty nexus – but it is far from the whole, not least because the nature and quality of the physical fabric remains an underappreciated or enumerated driver (or ameliorator) of poverty.

The most obvious manifestation of a definitional ambiguity of urban poverty is the reluctance of quantitative poverty specialists, who have just acclimatised to using multi-definitional approaches to poverty, to enter the definitional mire of ‘the urban’ even though, as several chapters in this book suggest, identifying or ‘seeing’ the urban poor is critical for both state and civil society (see also Scott, 1998; Beall and Fox, 2011; Mitlin and Satterthwaite, 2013). Recognising that poverty is not a uniform or singular experience means not only embracing multiple livelihood strategies, but also conceding poverty will vary in its manifestation over time and space (Bradshaw, 2002). The problem is that an inability to define ‘the urban’ means that innovations in measuring chronic and transient poverty at the city scale have lagged behind national and global assessments (c.f. Hume, 2005; Hume and Sheppard, 2003). The weak analytics for urban poverty in turn detract from sustained analysis of specific urban, place-based, drivers of poverty.

The absence of a global working definition of cities/towns/villages is especially tricky when the point is to talk about a physical form and scale of experience and not an administrative entity. Understanding what is meant by the city or urban scale is also complicated by the fact that in many parts of the world, especially Africa and South Asia, it is very difficult to distinguish peri-urban or low-density areas that either have no formal governance or where some form of subsistence livelihood prevails (Simon, 2008; Bryceson and Potts, 2006; Montgomery, 2008). Given that the informal or peri-urban fringe is often where the majority of poor residents live, it would seem logical to use the most inclusive and expansive definition of cities/towns/villages. If drawing the line between rural and urban is hard, so too is it difficult to distinguish the boundaries of cities – as inevitably large cities like Rio, Cairo, or Seoul sprawl way beyond their formal edge. Moreover, new city regions or conurbations, such as that of greater Lagos, are in formation (UN-Habitat, 2014). In the case of big cities it is especially hard to distinguish who actually runs the greater urban area, as it is rare that the metropolitan authority is the sole or even the most important political player in the city region. Despite the slippage in defining what an urban ar...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- 1 Poverty and the City

- 2 Women in Cities: Prosperity or Poverty? A Need for Multi-dimensional and Multi-spatial Analysis

- 3 Space and Capabilities: Approaching Informal Settlement Upgrading through a Capability Perspective

- 4 Constructing Informality and Ordinary Places: A Place-Making Approach to Urban Informal Settlements

- 5 Constructing Spatialised Knowledge on Urban Poverty: (Multiple) Dimensions, Mapping Spaces and Claim-Making in Urban Governance

- 6 Refugees and Urban Poverty: A Historical View from Calcutta

- 7 Expanding the Room for Manoeuvre: Community-led Finance in Mumbai, India

- 8 Where the Street Has No Name: Reflections on the Legality and Spatiality of Vending

- 9 Gangs, Guns and the City: Urban Policy in Dangerous Places

- Conclusion

- Index