eBook - ePub

Building High-Performance, High-Trust Organizations

Decentralization 2.0

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Some vanguard companies have evolved to a higher level of decentralization originating in the enabling-and-autonomy paradigm. A new kind of deep leadership is practiced by these spirit-driven organizations. This book brings together theory and case studies to cover historical origins and developments of both types of decentralization.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Complexity is a consequence of living in a sandpile world

In the business world, complexity has become the name of the game. The once still relatively rural global village has evolved into a sprawling, bustling, global city. New neighborhoods have sprung up energetically to economic prominence, while the overspending older ones have been complacently drowning in a quagmire of problems of their own making. Although the balance of power is shifting, all parts of this city are becoming more tightly interconnected and interdependent. The consequences of a seemingly insignificant event happening in one part of the city may unpredictably self-amplify, and spread uncontrollably like wildfire throughout the whole city, leaving its occupants in a state of dismay and feeling helplessly uncertain about their futures. Despite the ritual display of neighborhood leaders being firmly in control, there exists a general feeling that things are growing increasingly out of control.

For their fourth biennial Global CEO Study published in 2010, IBM researchers interviewed over 1500 CEOs, general managers, and public sector leaders worldwide. Contrary to previous reports where ‘change’ was consistently identified as their most pressing challenge, the CEOs reported that ‘coping with complexity’ was their new primary challenge. Alarmingly, they felt that while complexity was expected to continue to rise, the majority were open enough to admit that they felt unable to cope effectively with these new levels of complexity. The IBM CEO Study, titled ‘Capitalizing on Complexity,’ calls the difference between those CEOs (eight in ten) who anticipate higher levels of complexity over the next five years and those (fewer than half) who feel prepared to handle it, the ‘complexity gap.’ The study emphasizes that this 30 percent complexity gap is a ‘bigger challenge than any factor we’ve measured in eight years of CEO research,’ and concludes that the new reality is a world rapidly becoming a structurally different and ‘dramatically more complex’ system. The emergent complexity entails more volatility, uncertainty, and unpredictability. The roller-coaster behavior of the stock market since 2008 is merely an eerie epitome of what is happening on a worldwide scale in these CEOs’ business ecosystems.

Given the unsettling complexity gap, it is encouraging that CEOs identified ‘creativity’ ‘as the single most important leadership competency for enterprises seeking a path through this complexity.’ They were aware that, to start, they must deeply question their own leadership styles as well as their organizations’ ‘business models, old ways of working and long-held assumptions.’ Open-minded CEOs were to remove organizational silos and create ‘new and flexible structures for their businesses’ that respond quickly to changing customer needs. They were to ‘encourage experimentation and innovation throughout their organizations,’ reinvent their relationships with customers and ‘make customer intimacy their number-one priority,’ and so on. It all sounds somewhat familiar—even old hat—but taken seriously, as never before, the response to increasing complexity by enhancing creativity at all levels of thinking, and doing so throughout an organization, makes a lot of sense. And, as we will see, it is at least utterly sound from a systemic point of view to create more variety in organizational responses.

Admittedly, we do not feel very comfortable with the idea of a complex world. Our brains are just not wired to deal with complexity. We like simplicity and order better, simply because it is easier to adapt to a simple, predictable environment than to a complex, capricious one, as the systems scientist and mathematician Rapoport commented a long time ago. The search for simplicity, he argued, is almost an innate activity that may be rooted in a survival mechanism—predictability leads to the possibility of a quick response to, and control of, a situation. There is another good reason that we have become attached to our view of the world as a system of what is called organized simplicity. Ever since Isaac Newton published his Principia Mathematica in 1687, we have been led to believe that ours is a clockwork world, ruled by simple laws, as deterministic and predictable as falling apples and orbiting planets. One of the seven sages of ancient Greece, Thales of Miletus, became famous for his prediction of an eclipse of the sun. Legend has it that when Thales fell into a ditch, while studying the night sky, his female companion, probably somewhat jealously, commented, ‘How can you tell what’s going on in the sky, when you can’t see what lies at your own feet?’ We do not know Thales’ exact dates of birth and death, but we are almost certain that the eclipse took place on May 28, 585 BC. Newton’s ‘system of the world’ as he ambitiously framed it, was a gigantic mechanism, reliable and predictable like good old clockwork.

Of course, we have long been aware that very complex systems exist, such as gasses and liquids, composed of zillions of atoms and molecules. In principle, however, we believe that they all follow exactly Newton’s laws of motion, but in practice it is far too complicated to keep track of them—even with today’s powerful computers. Furthermore, the movements of the colliding molecules are completely erratic and disordered. They don’t go anywhere, which has actually given rise to the term ‘gas.’ The Dutch scientist van Helmont is said to have derived the word in 1632 from the Greek word chaos. With the help of statistics, however, we find that on average there are again simple statistical regularities in these, as they are appropriately called, systems of disorganized complexity. The triumph of simplicity and predictability again!

It was not until the second half of the last century, that this centuries-old and pleasantly reassuring dual mindset of organized simplicity and disorganized complexity was about to be revolutionized. In 1963, meteorologist and mathematician Edward Lorenz of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology published an inconspicuous paper with the delusively simple title ‘Deterministic Nonperiodic Flow’. It was so disturbingly paradoxical that it was completely overlooked—which proves again that you only see what you want to see. That deterministic systems could be nonperiodic was like cursing in the church of clockwork periodicity. Clocks, that is, the good old pendulum clocks, fortunately always return periodically to the same point. As happens often in the history of science—most recently with the 2013 Nobel prizewinner Peter Higgs’ first (rejected) article in 1964 on his famous particle, explaining the origin of mass—Lorenz’ paper was ignored for a decade.

Lorenz was interested in convection—think of the rising of hot air—an important subject for the study of weather. He used three over-simplified mathematical equations to describe convection, but there was a snag. Two out of the three equations contained a nonlinear term—changes in the two dependent variables were not quite proportional to the values of these variables. Not really a big deal, but it was unusual, because in the Newtonian world everything was linear. The problem is that, whereas linear equations can usually be analytically solved by pen and paper—that’s why Newton was so popular—nonlinear equations stubbornly resist such treatment. Fortunately, Lorenz was lucky because he had one of the first computers at his disposal. To his big surprise he discovered that his three variables at some point started to act strangely, when they were plotted as a function of time. As he wrote later in his path-breaking 1993 book The Essence of Chaos, they became ‘chaotic,’ that is, ‘seemingly random and unpredictable behavior that nevertheless proceeds according to precise and often easily expressed rules.’ (Differential equations are nothing but simple ‘rules’ to update the values of the variables as time progresses.) The plots of the variables as a function of time did not make any sense at all, no pattern, periodicity, nor predictability—indeed, just like the behavior of real weather. But remember, the equations, the rules underlying the dynamics of the system of variables, are still fairly simple and deterministic. The science of ‘deterministic chaos’ or, as I suggested in 1994, to fit the naming pattern of the previous two approaches to scientific problems, chaotic simplicity was born.

By accident, Lorenz discovered that his computer simulations were extremely sensitive to whatever initial conditions he gave them to start from. He called this the ‘Butterfly Effect,’ which implies that the flapping of a butterfly’s wings today—in Brazil, he actually said—may set off a tornado in Texas tomorrow; or it may not. Nothing is certain in a chaotic world. It became a famous expression, because underlying the chaos a new pattern was discovered, called a strange attractor, which showed that the trajectory of the chaotic system as a whole was moving at random round a strange figure that looked somewhat like a butterfly. It is interesting to note, without going into the mathematics, that there was a curious non-Newtonian circularity hidden in the equations of Lorenz’ simple model of convection flow. As said, there were three variables. Let’s call them X, and think, for example, of the flow velocity, Y, the temperature, and Z, the pressure. Mere inspection of the equations shows that X has an immediate effect on Z, and Z has an immediate effect on Y, and, here is the circularity, Y has an immediate effect on X again. So, each variable feeds, as it were, back on itself through the others. A small perturbation in one of them may, therefore, quickly amplify into a big disturbance. This is called positive feedback. In daily life we recognize these runaway amplifications as, for example, vicious circles, self-fulfilling prophesies, and stock market booms. On the other hand, a small perturbation may also be dampened to insignificance, something we call negative feedback. Now, it is important to know that a hallmark of complex systems is the presence of a multitude of these feedback loops, positive and negative, that are responsible for the complex and unpredictable behavior of these systems.

Science writer James Gleick, in his 1987 book Chaos: Making a New Science, all but immensely popularized the chaos movement. The upshot was the destruction of the Newtonian myth that simple deterministic systems could not behave randomly or chaotically and, therefore, become quickly unpredictable and uncontrollable. As Gleick put it, ‘where chaos begins, classical science stops.’ Lorenz thus confirmed what everybody knew, the weather never repeats itself. Locally small perturbations that go unnoticed may cascade into global catastrophes, or they may not. Nobody knows. It is unpredictable. The dream of all meteorologists that, with more powerful computers and an ever denser network of weather stations spanning the world, they could make better and better long-term predictions was shattered. Thanks to a simple butterfly.

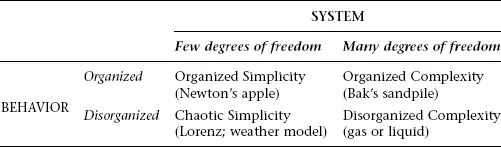

But chaos is not complexity. For sure, the Butterfly Effect makes it impossible to predict when and where an atmospheric depression may start to develop. But once it starts and the familiar beautiful depression spiral, as seen from above by today’s weather satellites, begins to evolve, forming a coherent pattern in which uncountable numbers of atmospheric particles organize themselves over long distances of hundreds of kilometers, we are witnessing an example of self-organization. Quite appropriately, this phenomenon is called organized complexity, a term that had been coined in 1948 by systems scientist Warren Weaver. He observed that the dual mindset of organized simplicity and disorganized complexity left out a host of interesting problems, which should also become subjects for scientific study. Long before organized complexity became a popular subject in the early 1990s, and before Lorenz’ discovery of chaos, Weaver noted that ‘scientific methodology went from one extreme to the other—from two variables to an astronomical number—and left untouched a great middle region.’ This region is characterized by problems with a considerable number of variables, but ‘the really important characteristic of the problems of this middle region, which science has as yet little explored or conquered, lies in the fact that the problems, as contrasted with the disorganized situations with which statistics can cope, show the essential feature of organization. In fact, one can refer to this group of problems as those of organized complexity.’ And he adds, ‘they are all problems, which involve dealing simultaneously with a sizable number of factors which are interrelated into an organic whole.’ Complex systems are indeed aggregates of many, sometimes very many, interacting components or elements. One may think of a developing embryo, the weather, an ecosystem, an economy, an organism, or the brain. To avoid confusion, and to summarize the various problems of science we have discussed, see Table 1.1.

Table 1.1 System vs behavior

To read the table, look at the top that says ‘system.’ Two kinds are distinguished, those with few degrees of freedom (df), that is, variables or components, and those with many variables or components. Then look at the left-hand side of the table, where we are interested in the ‘behavior’ of the system. This can be either organized or disorganized. Now you can read the table. Systems with few df showing organized behavior are in the category of Newtonian organized simplicity, while those with many df displaying disorganized behavior are categorized as disorganized complexity, and so on. Our focus will be on the upper right corner, problems of organized complexity, because that’s the kind of complexity we talked about at the start of this chapter, and it is characteristic for economies and business ecosystems.

So, what is this complexity? For a long time the subject has been somewhat vague and fuzzy, characterized by sayings such as ‘the whole is more than the sum of its parts.’ There are various definitions of complexity, but they usually add to the confusion and do not help our understanding very much. To really understand complexity we need a simple and comprehensible metaphor that helps us to grasp why, interestingly enough, widely disparate complex systems still display very similar behaviors. For more than a quarter of a century, a powerful metaphor has been available that explains in an uncomplicated way some important aspects of behavior common to very different complex systems. One aspect is the evolution over time of a complex system—how it works. And, it turns out to be highly relevant for our purposes of understanding complexity in the business world. Once you understand, it knocks your socks off, and will forever change your view of nature and, by the same token, your view of the business environment you are in.

In 1987 the Danish physicist Per Bak, together with two co-workers, published a short paper with the title ‘Self-Organized Criticality’ (SOC). It became one of the most cited papers of its time. In 1996, Bak published his seminal book with the gripping title How Nature Works, in which he gives numerous examples of SOC from earthquakes to the extinction of biological species, and from solar flares to stock markets. The fundamental idea is that complex systems composed of many interacting components organize themselves into a poised, critical state, way out of balance—and, importantly, without the interference of an outside agent. In this usually robust self-organized critical state, anything from small events to catastrophes can happen unpredictably, though surprisingly, according to well-defined statistical laws. The prototypical metaphor of SOC is the familiar sandpile, which best explains how it is that criticality generates complexity.

Go back to your childhood, and imagine you are on the beach. Start to trickle grains of sand through your fingertips on the flat surface of the beach. Initially, falling grains of sand upon hitting the beach stay close to where they land and will, at most, disturb a few other grains nearby. This is the subcritical state of the system with relatively little interaction between the various parts of the flat pile. Gradually, the sandpile increases in height with a slope that gets steeper and steeper, and every now and then we will observe little sand slides. At some point, on average, the slope will not get any steeper and we will observe that a single falling grain will induce avalanches of grains of all sizes spilling down the sides of the pile. Mostly we see many small avalanche events of a few toppling grains, sometimes somewhat bigger intermediate-sized avalanches and, more rarely still, a catastrophic avalanche in which almost the whole pile may collapse. This is the critical state of the system. It is important to understand that in the initial subcritical phase the fate of the falling grains can be explained in the old reductionist way of A hit B, which was leaning against C and D, so they moved over. But then the energy of the falling grain had been entirely dissipated, and the system had regained its equilibrium situation. However, in the critical state such an explanation will not do. The complex dynamics of the avalanches can only be understood as an emergent property of the sandpile as a whole, being in a critical state, far from equilibrium.

One may plot the number of avalanches N(s) of a particular size, the number of toppling grains, on the vertical axis against the size s on the horizontal axis. We may then see that for very small avalanche sizes the curve will peak, and with progressively larger sizes will drop off rapidly into the tail end of the curve. For this type of skewed curve it is more interesting when we plot the logarithm of N(s) against the logarithm of s. Now remember, log 10 = 1, log 100 = 2, log 1000 = 3, and so on, when the log has 10 as its base. The statistical distribution on a log–log plot turns out to be a remarkably straight line, with the high end at the upper left and the low end in the lower right of the plot, indicating inverse proportionality between log N and log s (see Figure 1.1). This is a so-called inverse power law. This means that an avalanche of, say, 1000 grains of sand is ten times less likely than an avalanche of 100 grains of sand, and is 1000 times less likely than an avalanche of ten grains of sand. Simple computer simulations as discussed in Bak’s 1987 paper, and empirical experiments with all sorts of real sand and rice grains—one of the preliminary experiments was done at IBM’s research center in New York, indicating IBM’s early interest in complexity—have generally confirmed these findings. This inverse power law is really the footprint of SOC. It can be found in all kinds of complex systems indicating that they are in a critical state, where a small perturbation (a single grain of sand) or fluctuation (a butterfly may flap its wings near the pile) may induce avalanche events of all scales.

One well-known example of this simple straight-line power law is the famous distribution of earthquake magnitudes called the Gutenberg–Richter law. In his book Bak clearly shows that in earthquake regions such as the south-eastern United States, about 1000 earthquakes of magnitude four on the Richter scale may occur per year. Then, about 100 ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Prologue

- 1 Complexity is a consequence of living in a sandpile world

- 2 Only variety absorbs complexity

- 3 Top-down decentralization and the folly of power

- 4 Going against the grain: aborted bottom-up decentralization

- 5 Commonsense decentralization by working with human nature–not against it

- 6 Deep leadership provides the social glue keeping high-variety organizations together

- Epilogue

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Building High-Performance, High-Trust Organizations by Gerrit Broekstra in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.