![]()

1

A Survey of Behavioral Finance

Abstract: This chapter presents the core ideas of behavioral finance. We provide a glossary of terms used in the field which will be referred to extensively in later chapters. We also provide a brief survey of the literature on important behavioral drivers of investment choice: investor preferences, beliefs, heuristics, and emotions. Lastly, drawing on the research findings of neuroeconomics, the neural basis of rewards, beliefs, heuristics, and emotions that affect investor behavior will be discussed.

Keywords: beliefs; emotions; heuristics; preferences; utility maximization

Fong, Wai Mun. The Lottery Mindset: Investors, Gambling and the Stock Market. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014. DOI: 10.1057/9781137381736.0006.

1.1The behavioral finance paradigm

Much of academic research in finance is built on the idea that investors are rational. Investors in these models maximize utility using all relevant information to construct “optimal” portfolios to balance risk and returns. These rational investors hold well-diversified portfolios to eliminate idiosyncratic risks that are not rewarded in efficient markets. They eschew active trading and follow buy-and-hold strategies that economize on trading costs.

Psychology research shows that real investors do not behave this way. Behavioral finance, which borrows heavily from psychology, has produced considerable evidence that most individual investors under-diversify (Barber and Odean, 2000; Goetzmann and Kumar, 2008), exhibit a “home bias” in their portfolios (French, 2008; Solnick and Zuo, 2012), trade excessively (Odean, 1999; Barber and Odean, 2000), and show a strong preference for speculative (“lottery-type”) securities such as those with high idiosyncratic volatility and high idiosyncratic skewness (Kumar, 2009; Mitton and Vorkink, 2007). There is also evidence that individual investors chase returns both directly and via mutual funds (Ippolito, 1992; Chevalier and Ellison, 1997; Bange, 2000; Frazzini and Lamont, 2008; Barber, Zhu and Odean, 2009a, b; Fong, 2014). Importantly, the average individual investor does all of these to his detriment.

In light of the growing body of evidence that investors are not completely rational, finance is evolving a new paradigm featuring investors who often act under the influence of behavioral biases, who trade on noise as if it were information, and who are sometimes driven by emotions and sentiment.

Behavioral finance is a big part of this new paradigm. The first behavioral finance paper published in a top-ranking journal appeared only in 1972 (Slovic, 1972). Since then, behavioral finance research has gradually gained momentum. Two decades later, the profession was confident enough to present an edited volume of collected papers with the title, Advances in Behavioral Finance. The editor was Richard Thaler, a pioneer in behavioral finance research. About the same time, two psychologists, Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, made seminal contributions to the study of individual behavioral biases which inspired a large volume of research in both theoretical and behavioral finance.

Kahneman and Tversky (1979) gave the world, Prospect Theory and its offshoot, Cumulative Prospect Theory (Tversky and Kahneman, 1992) as alternative models of how people actually make decisions as opposed to how they are supposed to act. In a series of path-breaking papers, they provide convincing evidence that the carriers of utility are gains and losses rather than final wealth, and that people’s judgment is heavily influenced by how a problem is framed (whether as gains or losses), their point of reference, and a host of other mental heuristics such as the availability heuristic, the representativeness heuristic, and anchoring (see Kahneman, 2011). These heuristics are mental shortcuts that produce quick solutions to the problems people face. While heuristics can lead to accurate decisions when the environment is predictable and the decision-maker has true expertise (think doctors and engineers), they can also lead to errors of judgment outside these domains. Moreover, due to deep-seated cognitive biases, these errors of judgment may become systematic: people may repeat these mistakes over and over again.

This is not a textbook on behavioral finance nor does it provide an in-depth survey of behavioral finance research. For readers who wish to get acquainted with the seminal ideas of Kahneman and Tversky, I recommend Kahneman’s (2003) insightful essay, “Maps of bounded rationality.” Kahneman’s recent book, Thinking Fast and Slow (2011) gives an authoritative and engaging account of the self-delusions that people fall prey to. There are also many excellent surveys of behavioral economics and finance. Early surveys include Thaler (1993), Rabin (1998), and Daniel, Hirschleifer, and Teoh (2002). Subrahmanyam (2008), Debondt et al. (2008), and Barber and Odean (2013) are more recent reviews of the literature.

This book is primarily about how individual investors reduce their wealth through suboptimal investment strategies. As we will show in the subsequent chapters, behavioral biases play a big role in explaining why individual investors persistently engage in money-losing strategies.

In general, people’s investment decisions are shaped by four factors: preferences, beliefs, mental heuristics, and emotions. An investors’ preference for one type of investment over others is driven by his goals and risk tolerance. While the traditional view is that all investors are risk-averse, in reality, people can be both risk-averse and risk-seeking. As Friedman and Savage (1948) pointed out long ago, people may purchase both insurance and lotteries. Shefrin and Statman (2000) developed behavioral portfolio theory to account for this behavior.

Investors’ investment choices also depend on their beliefs about financial markets and about their investment skills. A robust finding from psychology is that people are overconfident about their abilities to perform a variety of tasks such as driving, forecasting election outcomes and picking stocks (see, e.g., Alpert and Raiffa, 1982; Lichenstein, Fischhoff and Phillips, 1982; Odean, 1999). In experiments, overconfidence is manifested by subjects expressing overly narrow confidence intervals. Overconfidence is a powerful explanation of why investors prefer undiversified portfolios despite their patchy record of earning positive alphas from stock picking.

Investors’ beliefs are influenced by what others think. When most investors become overly optimistic or pessimistic about the market, sentiment-driven trading results. Keynes (1936) points out the possibility that significant numbers of sentiment-driven traders in the market can cause asset prices to deviate from their fundamental values. Shiller (2008) argues that investor sentiment, mediated by social contagion or herd behavior, accounts for some of the most spectacular episodes of stock market booms and crashes.

As noted, mental heuristics are rules of thumb that people use to find adequate but often imperfect solutions to complex problems. We use heuristics because it is mentally taxing to work out the ideal solution especially under the pressure of time. According to Kahneman (2011), the human brain operates at two levels in making judgments: System I and System II. System I provides quick and automatic solutions to a problem, while System II is slow, deliberate, and thoughtful. Heuristics are invoked when System I is in action. The many cognitive biases that influence individual investors indicate that people often rely on heuristics to make investment decisions, perhaps to a greater extent than they realize.

Finally, our investment decisions are also influenced by emotions, particularly, pleasure from gains, pain from losses, pride, and regret. While scientists still do not have a complete theory of how emotions govern risk-taking activities, evidence from brain imaging studies clearly show that brain areas that govern emotional states significantly influence people’s attitude toward risk and rewards.

The rest of this chapter summarizes research findings from psychology, neuroscience, and behavioral finance concerning the key factors that drive investors’ preferences, beliefs, use of heuristics, and sensitivity to emotions.

1.2Investor preferences

1.2.1 Mental accounting

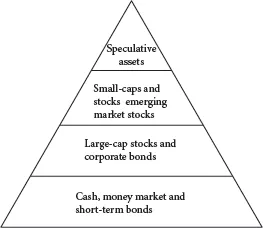

Modern portfolio theory (Markowitz, 1952; Sharpe, 1964) prescribes that investors should diversify optimally by taking into account the expected returns and correlation of assets. In reality, few individual investors follow this prescription. Shefrin and Statman (2000) argue that real investors apply mental accounting to organize their investments. Specifically, these investors think about their investment goals, then compartmentalize their goals using mental accounts where each account comprise assets whose return and risk characteristics match a specific goal. This approach leads to a pyramid-like structure of investments as shown in Figure 1.1.

At the bottom of the pyramid is a “safety account” where money is invested in risk-free assets such as cash, Treasury bills, and other money market securities. This layer serves as a liquidity fund and also as “insurance policy” against potential losses from investing in riskier assets.

Above the safety layer are other investment accounts aimed at achieving higher returns. As we move up the pyramid, the risk level increases. For example, the layer above the safety account might be invested in large-cap stocks and investment-grade corporate bonds. The next layer might consist of riskier securities such as small-cap stocks, below-investment grade bonds, emerging market stocks, and so on.

FIGURE 1.1 Portfolio pyramid

The top layer of the pyramid is essentially a gambling account. Securities held here include high-beta stocks, extremely volatile stocks, stocks with low book-to-market ratios (growth stocks), stocks with positively skewed returns, and those that have very high maximum daily returns in recent months. These stocks grab investors’ attention because of their large price movements and because they tend to attract more media attention than “boring stocks.”

Stocks with the above characteristics may also be termed lottery-type stocks. As argued by Barberis and Huang (2008), Barberis and Xiong (2012) and others, investors buy such stocks despite their low average returns for the chance of realizing extremely positive (“jackpot”) returns. Whereas lottery-type stocks have no special place in classical finance because investors are supposed to diversify broadly, research evidence shows that individual investors overweight these stocks relative to their market weights while institutional investors do the opposite. Lottery-type stocks fit rather naturally under the multiple account framework of behavioral portfolio theory.

One consequence of structuring investments using the pyramid model is that one does not explicitly factor in correlations between asset returns in the way that modern portfolio theory recommends. As such, the overall portfolio is unlikely to be mean–variance efficient. Nonetheless, the pyramid model is popular in real life. For example, contrary to the two-fund separation theorem, financial advisors often advise risk-tolerant clients to hold a higher ratio of stocks to cash and bonds compared to conservative investors (Canner, Mankiw and Weil, 1997). Rare is the financial adviser who proposes mean–variance efficient portfolios to his clients. Rarer still is an individual investor who structures his investments according to the principles of modern portfolio theory.

1.2.2 Preference for concentrated portfolios

A fundamental insight of modern finance is that it is difficult to consistently outperform the market. Diversification is therefore a sensible investment strategy. The average investor does not follow this prescription. Barber and Odean (2000) find that the average US household owns just four stocks. Goetzmann and Kumar (2008) report that even among professionals, the mean number of stocks owned is 4.86, while the mean number of stocks owned by experienced investors is less than 6. Of course, investors can and do diversify in other ways such as through mutual funds (Polkovnichenko, 2005). Still, US household data shows that the fraction of directly held equity holdings is significant. Consistent with other studies, Polkovnichenko (2005) find that about 80% of the direct investors hold fewer than five companies. The evidence indicates investors are not unaware of the importance of diversification. Rather, ...