- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Compliance Patterns with EU Anti-Discrimination Legislation

About this book

This book provides an in-depth and timely analysis of the member states' compliance patterns with the key European Union Anti-Discrimination Directives. It examines the various structural, administrative, and individual aspects which significantly affect the degree and the nature of compliance patterns in select European Union member states.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Compliance Patterns with EU Anti-Discrimination Legislation by Vanja Petri?evi? in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Civil Rights in Law. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Reassessing Compliance: Discrepancies in Application of EU Law

While the European Union (EU) finds itself in the midst of a protracted financial crisis, the persistence of racially and ethnically motivated violence constitutes an additional setback for the region. It is a sobering reminder that threats from racism and discrimination are more than relics of a distant past. The violent attacks on immigrants in Greece in May 2011,1 a brutal beating of a graduate student of African descent in Ireland in November 2011,2 racially motivated shootings in Italy and Belgium in December 2011,3 and Germany’s shocking discovery of a multi-year string of neo-Nazi murders (Crossland 2011), all present an alarming pattern of racially motivated violence in Europe. Given that the last half-century’s experiment in integration has been premised in part on the free movement of peoples, recent challenges to multiculturalism merit systematic attention. As economic austerity measures make groups at society’s margins ever more vulnerable, questions must by necessity be asked about responses from public officials at all levels. There is, indeed, mounting agreement that the EU cannot ignore the issue of discrimination or miscalculate the danger that this poses for its unity and long-term political and economic prosperity.

Despite implementation of new legislation, ten years of existing anti-discrimination directives, the broadened mandates of the “equality bodies,” and ongoing negotiations about—and expansions of—venues for democratic participation, the fact is that ethno-racial discrimination remains prevalent and “it is getting worse.”4 This book builds upon existing work in political science and organizational behavior to add important new explanations of member states’ efforts to outlaw discrimination within their jurisdictions. It also seeks to expose the underlying causes of state-level variation in compliance with EU Anti-Discrimination Directives. While some countries show far-reaching progress in implementing and complying with the anti-discrimination legislation, others lag behind in their legal commitments. The goal of this book is to identify and assess the explanatory power of several factors undervalued by the extant compliance literature. In particular, this study proposes a multilevel explanatory framework by identifying key factors at the structural, institutional, and individual levels that condition the patterns of variance in member states’ compliance and testing the least researched relationships within that framework.

Discrimination in the European Union

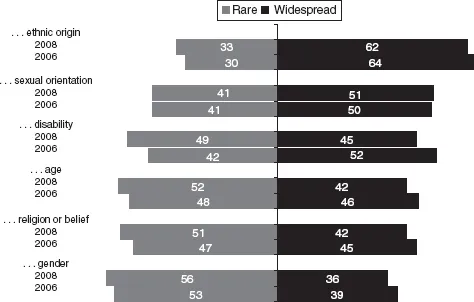

According to a 2008 Special Eurobarometer survey, ethnic discrimination has become a prevalent and recurring challenge for the Union and the then 27 member states. The survey illustrates that out of the different types of discrimination, “discrimination on ethnic origin [ . . . ] is seen to be the most widespread form of discrimination in the EU” (Figure 1.1)5 and the results of the first ever EU-wide survey, focusing exclusively on ethnic minorities and immigrants, reveal that racism and xenophobia continue to affect a significant number of EU citizens.6 Minorities are affected by discrimination in all aspects, and it penetrates into minorities’ daily lives from all corners and, with that, not only isolates them further into the ethnic enclaves but, more fundamentally, challenges the idea of Europe’s “common home.” Discrimination has plagued Europe for centuries, and it clearly continues today. The reemergence of structural barriers to minorities’ further integration (be it in employment, housing, or education), not to speak of verbal and physical attacks toward foreigners across Europe, is not only a reminder of Europe’s past but also an indication that there is no such place as a “safe haven” from ethnically motivated discrimination.7 According to the European Parliament, “the issue [of racism] is not one which the European Union can afford to ignore.”8 The EU faces the challenge of establishing a common identity.9

Figure 1.1 Perceptions of discrimination on the basis of [ . . . ].

NB: “Don’t know” and “nonexistent” (SPONTANEOUS) answers are not shown.

Note: 2008 figures based on EU 27, 2006 based on EU25.

Source: Special Eurobarometer 296, 2008.

In an attempt to contain and then reverse the rise in discrimination, the EU adopted a legal approach by implementing various directives with the goal of member states’ proper and timely adoption of its legislative framework. However, only recently has the EU gained additional powers to take action in the field of discrimination on grounds of sex, racial or ethnic origin, religion or belief, disability, and sexual orientation. Despite the fact that the EU was founded on the principles of liberty, democracy, and respect for human rights, for many years its institutions only dealt with discrimination based on “nationality” and “gender” (as these two grounds of discrimination have been conceived as primary threats to the functioning of the internal market during the 1960s and 1970s). However, the rise of extreme right parties, emergence of the Internet and its exploitation by propagandists, as well as cross-national racially-motivated collaborations gave a strong impetus for the establishment of an EU framework for combating racism. Thus, the adoption of the Amsterdam Treaty in 1997 (and specifically Article 13),10 which went beyond nationality and gender to include discrimination on grounds of sex, racial or ethnic origin, religion or belief, age, disability, and sexual orientation, “changed the way EU looks at questions of equality and anti-discrimination” (Nolan 2004, 4). Soon thereafter two directives, the Racial Equality Directive and the Employment Equality Directive, were adopted to provide a legal basis for the principle of equal treatment irrespective of racial or ethnic background. The transposition of the Directives into national legislation was to take place by 2003 for the EU-15, where May 1, 2004, was set for the then acceding ten member states, while Bulgaria and Romania had to transpose them by the date of their accession, which was January 1 of 2007.11

Of particular interest are the provisions of the Racial Equality Directive, which will be taken as a benchmark of how racial and ethnic discrimination is defined in this study. The Directive is the key piece of EU legislation with the purpose of providing legal measures for combating racial and ethnic discrimination. It sets out to eliminate four main types of discriminatory behavior. These include situations where a person is treated less favorably compared to another due to his or her racial or ethnic origin (direct discrimination), where a person is treated less favorably than another in a situation that appears to provide equal criteria for all (indirect discrimination), where a person’s dignity is undermined (harassment) and where instruction to discriminate on the basis of racial and ethnic origin is present. The scope of this Directive covers access to employment and working conditions, vocational training, organizational membership, social provisions, education, as well as provision of goods and services, including provision of housing. It was innovative in respect to requiring countries to establish not only judicial procedures to assess violations of equal treatment (especially in countries where such regulations had not previously existed) but also to institutionalize “equality bodies” to further the principle of equal treatment. Under the Directive, certain legal entities were also created in support of victims of discrimination and, aside from defining more clearly the concept of discrimination, the burden of proof was shifted in favor of the complainant; meaning, if discrimination had indeed taken place it should be brought only by the complainant him- or herself requiring the defendant to prove otherwise. The overall goal of the Directive was to provide ethnic and racial minorities with a right to equality and protection against discrimination before the law.

Enforcing European Union Anti-Discrimination Law

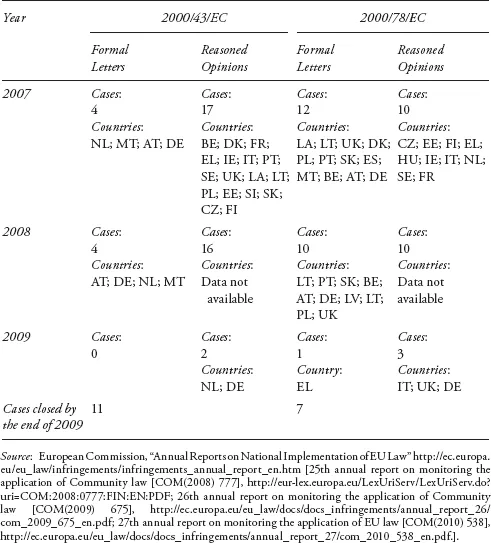

While the Directives have established minimum standards for combating discrimination, these standards are interpreted, transposed, and complied with differently in the various member states. Variation in compliance with the anti-discrimination directives can be observed from many aspects by examining the cases of infringements of the two Directives (Table 1.1), the role attributed to the equality bodies by the individual governments, and sanctions issued for violations of the principle of equal treatment. All of these are indicators of the compliance mechanisms that are currently in place within the individual member states. While some succeed in keeping a low profile in the infringement proceedings, empowering equality bodies and issuing sanctions when needed, others are far from fully complying with the Directives.

Table 1.1 Infringements of 2000/43/EC and 2000/78/EC

Since the adoption of the Directives in 2000, several countries were subject to infringement proceedings. For example, in the 2006 Letter of Formal Notice to the Czech Republic, the European Commission argued that the country failed in reference to several points, some of which included missing definitions of the various types of discrimination in the national legislation, insufficient grounds of protection for the individuals covered by the Directive, and absence of an equality body.12 In 2007 alone, the severity of breaches of the Racial Equality Directive varied across the EU. These ranged from lack of full protection against discrimination in various sectors of society (e.g., Czech Republic, Spain), limited transposition of the Directive to the field of employment (e.g., Latvia), or countries’ incorrect definitions of equal treatment (e.g., Slovakia) and racial harassment (e.g., Italy).13 Similarly, in 2008 several countries received Reasoned Opinions and Formal Letters for infringements of the Employment Equality Directive.14 For example, Lithuania received a Letter of Formal Notice in 2008 for violation of the Article 6(1) of the Employment Equality Directive, which refers to protection of age discrimination.15 While some cases were closed by the end of 2009, in 2010 and 2011 new Reasoned Opinions were issued and referrals were made to the European Court of Justice for breaches of EU law. In 2010, the European Commission referred Poland to the European Court of Justice for incorrect transposition of the Racial Equality Directive. Aside from the employment sector and at the time of this research, Poland does not have any legislation outlawing ethno-racial discrimination in access to social services, housing, and education, among other sectors covered under the Racial Equality Directive.16 In 2011, Italy received a Reasoned Opinion for nationality-based discrimination in recruitment of university professors, and was referred to the European Court of Justice for discrimination in access to public sector employment.17 In addition, Spain and Greece received Reasoned Opinions for nationality-based discrimination in access to public sector employment that same year.18

In addition, both Directives mandate the establishment of the equality bodies that are to take responsibility in monitoring and, in the long-run, eradicating discrimination. While some member states have taken a lead in establishing equality bodies, others have rather remained silent on that issue. Statistics indicate that the Czech Republic, Luxembourg, and Spain were lagging behind in the establishment of equality bodies and only established them several years after the adoption of the Directives.19 In other cases, the already established equality bodies have limited powers. For example, the Greek Ombudsman plays a mediating role without having authority to issue sanctions or legally support victims in court proceedings. Rather, it can make recommendations that, in turn, are not legally binding for the authorities. Similar statements can be made for equality bodies in Lithuania, Denmark, and Cyprus. Lastly, some equality bodies are considered ineffective in terms of receiving and processing ethno-racial and discrimination-related complaints, as indicated by the cases of Poland and Slovenia.20

The absence of sanctions in ethnic and racial discrimination cases is another, indirect, indication of the effectiveness of the anti-discrimination directives. Based on data collected between 2006 and 2007, 12 countries did not apply any sanctions. These countries either did not have an equality body in place or did not have an equality body capable of taking on cases of discrimination effectively. Countries with ineffective equality bodies usually lack the institutional framework necessary for proper representation of victims as well as imposition of sanctions. On the other hand, the United Kingdom is a leader in issuing sanctions, and in differentiating among the various types of sanctions needed in ethno-racial discrimination cases. Between 2006 and 2007, the United Kingdom issued the highest number of sanctions across the EU. Furthermore, progress has been noted in Italy where the Italian equality body (UNAR) made agreements with two lawyer associations regarding free legal assistance to victims of discrimination. The rest of the EU countries have varying degrees of issuing sanctions in cases of discrimination. Austria and Malta have had the least number of sanctions applied in 2007 whereas Ireland had 24 sanctions applied within that same year. The number of sanctions imposed for cases of discrimination in 2007 varied among countries as exemplified in the case of Latvia where ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 Reassessing Compliance: Discrepancies in Application of EU Law

- 2 Explaining Factors Affecting Compliance

- 3 Conceptualizing Compliance with the Anti-Discrimination Directives

- 4 Cross-Country Perspective: The Influence of Government Structure on Compliance

- 5 Intra-Country Perspective: The Case of Slovakia

- 6 Concluding Remarks and Implications for Future Research

- Appendices

- Notes

- References

- Index