eBook - ePub

Democracy Promotion by Functional Cooperation

The European Union and its Neighbourhood

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Democracy Promotion by Functional Cooperation

The European Union and its Neighbourhood

About this book

This book presents a novel 'governance model' of democracy promotion. In detailed case studies of EU cooperation with Moldova, Morocco, and Ukraine, it examines how the EU promotes democratic governance through functional cooperation in the fields of competition policy, the environment, and migration.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Democracy Promotion by Functional Cooperation by Tina Freyburg,Sandra Lavenex,Frank Schimmelfennig,Tatiana Skripka,Anne Wetzel,Anne Wetzel,Tatiana Skripka,Sandra Lavenex in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & American Government. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Models of EU Democracy Promotion: From Leverage to Governance

The European Union’s distinct constitution as a political system sui generis has implications for the nature of its external relations. EU foreign affairs encompass much more than limited intergovernmental cooperation in the framework of its Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP)/European Security and Defence Policy (ESDP). They include a whole range of activities such as trade, aid, development, and enlargement and association policies such as the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP), as well as the external dimension of sectoral policies in a variety of fields such as environment, energy, and migration.1 This mosaic of EU external policies opens up a variety of possibilities for the promotion of democracy outside the EU’s borders.

We understand democracy promotion as comprising non-violent activities by a state or international organization that have the potential to bring about, strengthen, and support democracy in a third country. This covers the sum of voluntary activities adopted, supported, and (directly or indirectly) implemented by foreign actors that are designed to contribute to the democratization of autocratic regimes or consolidation of democracy in target countries. This definition explicitly excludes the use of physical coercion and all covert activities, such as silent diplomatic efforts. Yet, it acknowledges the democratizing effect of cross-national activities without explicit agency, such as migration or communication.

We argue that the multifaceted nature of EU democracy promotion falls into three distinctive ideal-typical models: leverage, linkage, and governance. Each of these models is rooted in a different understanding of EU external actorness and holds a distinct conception of the way in which democratic principles and practices can be promoted in non-member states. The linkage and leverage models constitute traditional approaches to external democracy promotion (Levitsky and Way 2006). They have their roots in the main theories of democratization developed in the 1960s and 1980s. The linkage model emphasizes the structural prerequisites for democracy (Lipset 1959) and aims at facilitating endogenous democratization through socio-economic development and transnational exchange. In this case, international actors such as the EU give economic aid, promote societal interchange, and sustain democratic civil society groups in order to facilitate democratization from below. Leverage, in contrast, links up with the literature on democratic transitions that focuses on the role of ruling elites in promoting regime change (O’Donnell et al. 1986; Przeworski 1991). As a democratization strategy, it induces power holders to give up authoritarian rule in exchange for other (significant) benefits, such as, in the European case, EU accession.

In recent years, the intensification of transgovernmental cooperation across functional policy areas has given rise to a third approach that we coin the ‘governance’ model of external democracy promotion (Freyburg et al. 2009; 2011; Lavenex and Schimmelfennig 2011). This approach is based on the transfer of democratic governance principles related to transparency, accountability, and participation in the context of functional cooperation between administrative actors. While not tackling the reform of political institutions as such, or the socio-economic prerequisites of democracy, this ‘third way’ of democracy promotion prepares a legal–administrative basis for democratic governance and constitutes an important element in the process of transition.

This book focuses on the EU’s democratic governance promotion in three countries of the ENP: Moldova, Morocco, and Ukraine. The contribution of the two traditional models, leverage and linkage, is examined in Chapter 2. While we recognize the enduring relevance of the linkage and leverage models of democracy promotion, we argue that their impact is limited in the case of the ENP countries. In contrast, the governance approach appears better suited to the conditions for democracy promotion in the EU’s neighbourhood. First, it is in line with the main thrust of the EU’s external action and the ENP: the creation of policy networks and transfer of EU policy rules (Lavenex 2008). Second, it is less overtly political. Because democratic governance rules come as an attachment to material policies, do not target change in basic structures of political authority, and focus on public administration rather than societal actors, they are less likely to arouse suspicion and opposition from third country governments (see Freyburg 2012a; 2012c).

Models of democracy promotion

The three models of democracy promotion presented in this chapter can theoretically be applied by every international actor. Their inclusion in EU external relations has been influenced by both the internal development of the EU and changes in the external context. The linkage approach has been a constant in EU external policies since the EU’s early support for democratic transitions in Latin America in the 1980s (Smith 2008: 122–9). The EU’s roots in economic integration, its early adoption of a development policy, and its long-standing cooperation with former European colonies were conducive to the formation of linkage policies. A more favourable international context, however, with the implosion of the Soviet Union and the growing assertiveness of the EU as a foreign policy actor in its own right, prompted the EU to increasingly adopt leverage policies. Democracy, human rights, and the rule of law became ‘essential elements’ in almost all EU agreements with third countries as both an objective and a condition for institutionalized relationships. In the case of violation, the EU introduced the (theoretical) possibility of suspending or terminating the agreement (Horng 2003).

The leverage approach became dominant in the European context after the end of the Cold War. The political integration symbolized by the creation of the EU coincided with the transformation of many Eastern European countries and these countries’ gradual rapprochement with the EU. While the EU continued to give support to democratic transition in Central and Eastern European countries through economic aid and targeted action towards civil society, it also embraced a more explicit and direct approach to democracy promotion by making aid, market access, and deeper institutional relations, from association to membership, conditional on third states’ progress in democracy. Most notably, the Copenhagen Criteria agreed by the European Council in 1993 made the consolidation of liberal democracy the principal condition for starting accession negotiations. However, with the completion of the Eastern enlargement rounds in 2004 and 2007, leverage through the promise of enlargement has lost its status as the pre-eminent democracy-promotion strategy of the EU. Although political conditionality remains an important declaratory instrument in the EU’s external relations and is still dominant in the accession strategy for the Western Balkans, its practical relevance is limited outside the enlargement context, where it cannot rely on the attractiveness of membership.

The governance model has come to complement the two traditional approaches in recent years with the implementation of new association policies below the threshold of membership. This approach consists in the promotion of democratic governance norms in functional cooperation with third countries and works through the approximation of sectoral rules to those of the EU. This functional approach operates at the level of democratic principles and practices embedded in the governance of individual policy fields and unfolds through the deepening of transgovernmental, horizontal ties between the EU and third countries’ public administrations. The ENP, which the EU designed as an institutional framework for managing relations and deepening cooperation with the non-candidate countries of Eastern Europe, Northern Africa, and the Middle East, is a primary example of such functional governance. It proclaims shared values, including democracy, human rights, and the rule of law, to be the basis of neighbourhood cooperation and links the degree of cooperation to the adoption of these values by the neighbourhood countries (European Commission 2004a). In practice, however, it is up to the neighbouring countries to decide on the extent to which they will adopt the EU’s provisions on democracy, human rights, or the rule of law, and non-adoption does not prevent close cooperation in sectoral policies. Considering the constraints on democracy promotion outside the enlargement framework, the European Commission itself suggested refocusing the EU’s efforts from the promotion of democratic regimes to the promotion of democratic governance – that is, more transparent, accountable, and participatory administrative practice even in autocratic states (European Commission 2006a: 6).

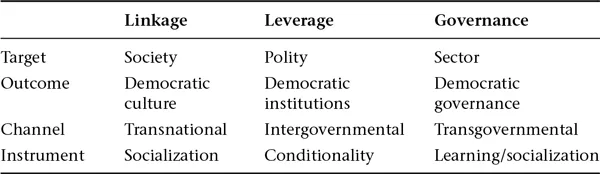

The three ideal-typical models of democracy promotion – linkage, leverage, and governance – can be distinguished on four main dimensions: the target system of democracy promotion, envisaged outcome, main channels, and typical instruments. ‘Linkage’ is a strategy targeted at the societal prerequisites for democracy. It seeks to prepare the ground for the emergence of a democratic culture in society. Linkage activities operate through transnational channels and involve the socialization of societal actors into democratic norms. ‘Leverage’, in contrast, directly addresses power holders in the government. Its target is the reform of the polity, and the intended outcome is the set-up of democratic institutions guaranteeing vertical (electoral) and horizontal accountability, respect for individual rights and civil liberties, and rule of law. This model typically applies political conditionality in inducing ruling elites to engage in democratic reforms. It thus operates at the level of intergovernmental cooperation between the EU and third country governments.

Our third model, ‘governance’, addresses more subtle forms of democracy promotion. Its target is narrower, since democratic governance refers to pro-democratic policy making within individual sectors, such as environmental policy, market regulation, or internal security, rather than the state’s macro-institutions or the entire society. The goal of democratic governance promotion is the transfer of procedural principles of democratically legitimate political–administrative rule, including transparency and accountability of public conduct, and societal participation in policy making. The channels through which these principles are promoted are transgovernmental networks that bring together public administrators from democracies and non-democracies. The transformative influence works mainly through the mechanisms of learning and socialization. In principle, democracy-promotion efforts may be conceived as freely combining specific features across all four dimensions. However, both theory and practice have tended to concentrate on the three ideal-typical combinations, as summarized in Table 1.1. In the following, we outline the three models of democracy promotion in more detail and specify the conditions under which they are effective.

Linkage

The linkage model locates democracy promotion at the level of society and targets the socio-economic preconditions for democratization, including economic growth, education, spread of liberal values, and self-organization of civil society and the public sphere. The envisaged result is a democratic, ‘civic’ culture and meso-level institutions such as civic associations, parties, and a democratic public sphere.

Democracy promotion through linkage involves both indirect activities that address the societal preconditions for democracy and direct activities such as giving support to democratic opposition and other civil society actors in the target countries. In both cases, the role of the external actor consists in enabling and empowering societal, non-governmental actors to work for the democratization of their home country from below.

Table 1.1 Three models of democracy promotion

Indirect linkage activities take their justification from the modernization account of democratization (Lavenex 2013: 137f.). They connect with Seymour Martin Lipset’s notion that only in a wealthy society can a situation exist in which ‘the mass of the population could intelligently participate in politics and could develop the self-restraint necessary to avoid succumbing to the appeals of irresponsible demagogues. A society divided between a large impoverished mass and a small favoured elite would result either in oligarchy [ … ] or in tyranny’ (Lipset 1959: 75). Rather than affecting the short-term calculations and power resources of governments and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), external democracy promotion helps to transform the environment and socio-economic structures of third countries. In his pioneering study of the social conditions or ‘requisites’ that support democracy, Lipset identified economic development – broadly understood as a syndrome of wealth, industrialization, urbanization, and education – as the most important factor. Economic development is accompanied by better education, less poverty, and creation of a large middle class and competent civil service. It thereby mitigates the class struggle and promotes cross-cutting cleavages. In addition, it nurtures belief in tolerance and gradualism and reduces commitment to extremist ideologies. In sum: ‘[t]he more well-to-do a nation, the greater the chances that it will sustain democracy’ (Lipset 1960: 31). The relationship between economic well-being and democracy has been tested on the basis of various indicators and methods and in comparison with many alternative factors, and has proven highly robust (Diamond 1992; Lipset 1993). More recent analyses have sought to disentangle the correlation between economic development and democracy – whether economic development triggers and/or sustains and consolidates democracy, or the other way round (Przeworski et al. 2000 versus Boix and Stokes 2003) – and the causal mechanisms linking the two (Acemoglu and Robinson 2006). However, this debate has left Lipset’s main correlation intact (Boix 2003; Inglehart and Welzel 2005).2 As a mechanism that emphasizes domestic, societal, and bottom-up factors of democratization, economic development provides the starkest contrast to political conditionality, an international, political, and top-down mechanism. The linkage model thus expects the level of democracy in a country to increase with the level of economic development.

How can specific activities of the EU contribute to such socio-economic development? First, the EU may promote the economic development of target countries. By increasing trade relations, investment, and development aid, it can contribute to democracy-conducive wealth in general (Sasse 2013). The positive effects of aid, trade, and investment may increase with diversification, in two respects. On the one hand, they are most helpful if they do not simply advantage small economic elites but if their benefits are spread out as broadly and evenly as possible across the population, thus contributing to general wealth and higher income equality. On the other hand, they are most likely to promote democratization if they strengthen mobile assets rather than immobile assets. When pursing democracy promotion through linkage, the EU would therefore have to focus its trade and investment on the industrial and services sectors rather than nurturing agricultural or primary resources sectors in the target states. Thus, the effectiveness of EU linkages increases with EU trade, aid, and investment, in particular if the benefits reach society at large and are concentrated in the secondary and tertiary sectors of the economy.

Second, the effectiveness of linkage increases with EU support for education in the target societies. By helping to raise the levels of literacy and education in the target societies – that is, through building schools and universities, funding educational programmes, further educating teachers, welcoming students – the EU can prepare the ground for successful democratization in the future. The contact hypothesis predicts that the effectiveness of democracy promotion increases with frequency and intensity of contacts between the EU and the target society. Through business contacts, work or study abroad, tourism, longer-term migration, and media exposure, target societies may come into contact with democratic ideas and practices. To the extent that these contacts convey an attractive social and political alternative, they may contribute to value change and inspire a higher demand for freedom and political rights in the target countries.

As mentioned, democracy promotion through linkage can also involve direct activities. The EU, for instance, gives money to pro-democratic civil society organizations or parties or provides them with infrastructure such as computers, mobile phones, or photocopying machines. Civil society support programmes also include the organization of meetings, seminars, and conferences that help these societal organizations to improve their political strategies and cooperation. This leads us to the general expectation that the effectiveness of linkage increases with the intensity of EU support for pro-democratic societal organizations.

In sum, we hypothesize that the more the EU supports pro-democratic civil society organizations and socio-economic modernization of target societies, the more the linkage model of democracy promotion will be effective (see Chapter 2). However, for this to be possible, and to produce demand for (more) democracy from below, both direct and indirect activities require a modicum of transnational openness on the part of the target country and of autonomy for the civil society. Linkage efforts will not reach civil society if a country is isolated from the outside world and civil society has no freedom to manoeuvre. Thus, the effectiveness of linkage also increases with the external accessibility and domestic autonomy of civil society.

Leverage

The leverage model is the most direct democratization strategy, as it is targeted at the polity as such and its constitution. This model speaks to actor-centred theories of democratization that emphasize the role of political processes and the choices of state leaders in explaining regime change (O’Donnell et al. 1986; Przeworski 1991). These actor-oriented approaches argue that regime transitions are not determined by structural factors, but are shaped by the principal political actors’ interests and strategies in a given setting. As Shin (1994: 141) expressed it, democracy ‘is no longer treated as a particularly rare and delicate plant that cannot be transplanted in alien soil; it is treated as a product that can be manufactured wherever there is democratic craftsmanship and the proper zeitgeist’. Political change can, therefore, be externally induced through offering ruling elites attractive benefits, provided that these benefits are not exceeded by the corresponding costs of compliance.

In order to produce institutional reform through leverage, the EU uses political conditionality. Conditionality is best conceived as a bargaining process between the democracy-promoting agency and a target state (Schimmelfennig and Sedelmeier 2005a: 12–16). In a bargaining process, actors exchange information, threats, and promises in order to maximize their utility. The outcome of the bargaining process depends on the relative bargaining power of the actors. Informational asymmetries aside, bargaining power is a result of the asymmetrical distribution of the benefits of a specific agreement (compared with those of alternative outcomes or ‘outside options’). Generally, those actors who are least in need of a specific agreement are best able to threaten the others with non-cooperation and thereby force them to make concessions.

In using conditionality, the EU sets the adoption of democratic institutions and practices as conditions that the target countries have to fulfil in order to receive rewards from the EU – such as financial aid, technical assistance, trade agreements, association treaties, and, ultimately, membership. States that fail to meet the conditions are n...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- About the Authors

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1. Models of EU Democracy Promotion: From Leverage to Governance

- 2. The Limits of Leverage and Linkage in the European Neighbourhood

- 3. Democratic Governance Promotion

- 4. EU Promotion of Democratic Governance in the Neighbourhood

- 5. Moldova

- 6. Morocco

- 7. Ukraine

- 8. Democratic Governance Promotion in a Comparative Perspective

- 9. Conclusion and Discussion

- Appendices

- Notes

- References

- Index