- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

What was it like to work behind the scenes, away from the spotlight's glare, in Hollywood's so-called Golden Age? The interviews in this book provide eye-witness accounts from the likes of Steven Spielberg and Terry Gilliam, to explore the creative decisions that have shaped some of Classical Hollywood's most-loved films.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Those Who Made It by John C. Tibbetts in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Innovations in 1920s and 1930s Hollywood Cinematography, Sound Technology, and Feature-Length Animation

The American film industry was in a hurry to grow up, from the early ‘teens to the 1930s. The ragtag nickelodeon days transformed into Classical Hollywood’s studio structures and star system. East and West Coast became configured as, respectively, the business and the production ends of the studios. The vertical integration of the studios had begun, insuring that the film product would be produced, distributed, and exhibited under one banner. Cinematographer Glen MacWilliams, sound technician Bernard B. Brown, and Disney animator Ollie Johnston were the children of this era. In their respective fields, they were eyewitnesses to the development of sophisticated camera techniques, talking-picture technology, and the maturation of the animated feature film. For a useful overview of the early days of the emerging studio system, see Janet Staiger, Ed. The Studio System (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, NJ, 1995).

Cinematographer Glen MacWilliams: “We were trained by trial and error!”

Seal Beach, CA, June 1978

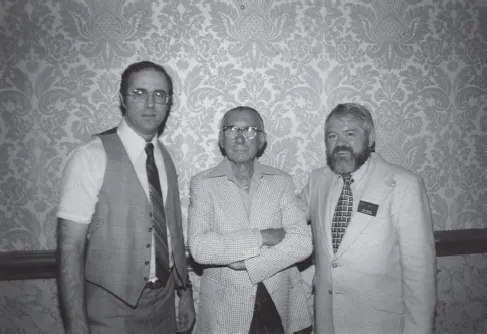

Figure 1.1 Glen MacWilliams and John Tibbetts on the occasion of the National Film Society’s Artistry in Cinema Awards, Hollywood, June 1978. James M. Welsh at the Far Right

I first met Glen MacWilliams (1898–1984) on a sunny June afternoon near his home on Seal Beach in 1978. As a recipient of the National Film Society’s Heritage in Film Award, he had screened Jessie Matthews’s Evergreen (1934), one of several Matthews musicals he had photographed during his years in the UK. What an amazing career MacWilliams had: photographing Douglas Fairbanks westerns and Jackie Coogan vehicles in the ‘teens and ‘20s; Jessie Matthews musicals in the ‘30; Alfred Hitchcock features in the ‘40s; and television series in the ‘50s and ‘60s. Now, at age 80, he was no longer the 12-year-old boy squinting into the bright sun, but a seasoned veteran of Hollywood affectionately reviewing his rich and varied past.1 A touch of genteel English charm pervades the air as he and his lovely wife Marie share tea and cakes with me. I can still hear his firm but gentle voice … as he conjures up a Hollywood that most of us know only from the history books.2

JOHN C. TIBBETTS: You must have been just kid when you started in the movies!

GLEN MACWILLIAMS: I was a high school dropout from Hollywood High in 1912. During the summer time and on Saturdays I would work in a grocery store, right off Sunset Boulevard. I was 12. Saturdays I would take out a white horse-and-buggy and get orders from the customers, come back to the store, fill them, and deliver them in the afternoon. One day my boss, Mr. Hill, gave me an envelope and said, “Glen, take Mrs. Bitzer’s order this afternoon, give her this envelope, and she’ll give you a check.” The name Bitzer didn’t mean anything to me. So I took out the buggy and gave her the envelope. It’s a paycheck for $250. I said to myself, that’s a lot of money! She told me Mr. Bitzer was a cameraman.3 I said, “What’s that?” She explained. Well, I was getting two and a half dollars a week, and here’s a cameraman making $250! The seed was planted.

So much for high school!

Well, I entered Hollywood High with the idea that I would be a civil engineer. They threw the algebra book at me, and I became convinced I didn’t want any part of that! So I picked up my lunch pail, took the streetcar home, and told my mother I had quit. Dad came home that night and after dinner I had to tell him. He was in politics at the time (the Mayor’s secretary) and was able to get me a job at Parmalee Dohrman’s: a store that specialized in fine china crystal and household wares of high quality. There I was one day, day-dreaming, and blam! there went a china turkey platter—smashed into pieces. Immediately, I got my coat and lunch box and walked up to Sunset Boulevard. Along came an empty watermelon wagon returning to San Fernando Valley. I hopped on. I’m scared to go home. I have no idea where I’m going. About three miles from my house I jumped off and immediately felt this hand on my shoulder and a voice saying, “Hey kid, you want a job?” Well, I had no idea what was going on. He took me into a room where he put some stuff on my face and introduced me to a man named Eddie Dillon. He explained that he was making a motion picture and needed a boy quickly. I didn’t know what he was talking about!

It sounds like a fairy tale!

Yeah, well, it gets better! Anyway, he told me to go down a hallway and knock on a door. So I went, and the minute I reached the door, I was hit from every angle. A bunch of kids jumped me and started beating on me. Then the director ran over and exclaimed, “Aw, Glen, that was wonderful!” Mr. Dillon explained to me that they were making a movie and that all the office boys in the building were out on strike. I was supposed to be a “scab” applying for a job.

And you got paid …?

I got five dollars and 35 cents pay, and they told me to come back the next day. Emmett Rice was the name of the assistant director of that thing. The next day I came back and we went to an exterior location for the same sequence. Meanwhile, I was wondering how to tell my folks about all this. I didn’t want to lie to my dad. I had to tell him the whole story. My career as a child actor had begun! I found out later, incidentally, that I was in the same studio where Billy Bitzer worked.

When did you become interested in the camera?

Oh, all the time I was fascinated by the camera. In those days the assistant cameraman had to guard the camera because of the violence in the Patents War.4 We had a white sheet and if we’d see anybody with a camera, we’d drape the sheet over ours to keep it from being photographed as evidence. Nobody could get near it, either. There was another assistant by the name of Oliver Marsh. When he was promoted to cameraman, I got on his back to make me his assistant. I hounded him to death and finally I made it. This was after about a year as a kid actor.

It happened just like that? No prior training?

In those days if anyone asked you if you could do this or that, you didn’t dare say no. You’d say, “Yes, of course!” So there I went, working as assistant cameraman and not knowing much about it at all. The first picture we did was with Dorothy Gish and Robert Harron at a Bear Valley location. The director was Donald Crisp.

I asked Glen about the problems that inevitably would confront a fresh-faced kid manhandling a strange camera. He spoke warmly about those first trials he had to face, never sparing himself in recounting some of the more embarrassing moments …

Take that time up in the Bear Valley location: The Pathe camera had 400 foot magazines. Oliver needed a new load, so he took out the exposed magazine, gave it to me, and told me to replace it. I passed Donald Crisp and he said, “Hey, sonny, come here.” Now there were velvet-lined light traps in the film magazines, and I was carrying it with the light traps up, which allowed the sunlight to enter if they leaked. Crisp noticed this and said, “Does that magazine have film in it?” I opened the magazine in full sunlight and looked in and replied, “Yes, it’’s full!” Now what do you do with a situation like that? Can you imagine anything so horrible if you were a director, to have a nitwit assistant cameraman up in Bear Valley with a limited quantity of film, and there’s 400 feet of it, wasted? Well, I didn’t get fired. I got a raise! The point I am driving at is that at that time in the motion picture industry there were very few experienced assistant cameramen. All technicians had to be trained, but by trial and error. Now here I am, a kid who talked his way in (I had really sold Oliver Marsh a bill of goods!) and now both Oliver and I are in a hell of a spot. For him to tell the truth about me would make him look stupid. So nothing happened to me. I lived it down and never made that mistake again …

Working methods

Any viewing of most silent films quickly reveals a relative lack of camera movement. This was not because panning and trucking techniques had not occurred to the early cameramen. Some films from the turn of the century demonstrate astonishing examples of such camera movements. But moving the hand-cranked camera was difficult.5 I asked Glen to explain.

The tripod head was equipped with two cranks. One was for panning and the other for tilting. Obviously, panning and tilting were quite restricted; because, having only two hands, one had to be cranking the camera. There was a lock release under the tripod head which permitted transferring the head from a standard tripod to a “baby” tripod. One day I got the bright idea of lashing a piece of broomstick to the head, placing the other end under my arm against my body. I could pan the camera by swiveling my body. Perhaps the invention of the “free head” evolved from this. I do not know.

But how were you able to maintain a steady, consistent crank rate?

Only by practicing with an empty camera. Normal cranking was about 12 frames per second. [Pantomimes turning a crank] Now, when these old films are shown on television, they are run at 24 frames per second which, of course increases the speed of the action.

Did you ever vary the crank rate within a shot?

Sure. Let’s say you’re shooting a comedy. You started out at 16 frames per second. Then for the chase you dropped down to eight frames. But it’s not that simple. You have to then compensate by cutting your exposure in half. All the while the director is shouting out for me to change camera speed, and I’m having to make all these adjustments.

It was fairly common, then, to vary the crank rate?

Oh yes. It’s harder in sound films unless you’re over-laying the sound track. I remember back in the silent days when I was a second cameraman on Doug Fairbanks’s He Comes Up Smiling (1917) they wanted footage of a swarm of bees that takes after Doug. I went out to an aviary to get this footage. I got the camera set up and I cranked a lot of stuff which I took to the lab, bragging all the while about what great footage I had. The next morning I’m called in and they want to know what this footage is. I told them bees. Well, they showed me the stuff and it looked crazy. It was like looking at a bunch of worms crawling around. For every frame the bees had moved so far, see, and all I ended up with was what looked like a bunch of wriggling strings.

What should you have done—crank faster?

Why, certainly. It never dawned on me that you have to do the same thing with action as with miniatures, right? If you scale a miniature down to one-tenth the normal size, you have to increase your crank speed ten times to make it normal. Well, here these bees looked like so much spaghetti! No one had told me to over crank.

How about motorized cameras—when did they come in?

About 1927, when the Mitchell camera company introduced motors with a variable speed control.

Just what was the difference in those days between “assistant” and “second” cameraman?

The assistant cameraman’s job in those days was quite different from what it is today. He literally assisted the cameraman. Among his duties, were setting up the camera, setting up the still camera (there were no still cameramen, per se, in those days), keeping a diary of each scene shot, and the number of feet that it ran—and much, much more. In fact, you might say he was one of the most responsible people on the set. When the day’s shooting was over, he took the exposed film magazines into his darkroom, unloaded them and took the cans of film to the laboratory for development. One careless act, such as turning on a light in his dark room could blow the whole day’s work. Don’t ever sell those assistants short! Today, however, it is quite different. There can be as many as four or five assistants (depending upon the size of the production), each having his own particular job. Film loaders, for instance, are responsible for just loading and unloading the magazines, etc. The second cameraman always set up as close to the first cameraman as possible because two negatives had to be shot. They didn’t make dupe negatives then. They were so terribly grainy. This other negative, the foreign negative, would be shipped off for foreign release. On a lot of occasions we wo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Foreword by David Thomson

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Interviews and Conversations

- 1 Innovations in 1920s and 1930s Hollywood Cinematography, Sound Technology, and Feature-Length Animation

- 2 Hollywood at Home and at War in the 1940s

- 3 Cold War Film and Television in the 1950s

- 4 “New Hollywood” Filmmakers in the 1970s and 1980s

- 5 Late Twentieth Century Cultural Inclusion

- 6 Epilogue: Past is Prologue

- Notes

- Index