![]()

1

A Market for Payments – Payment Choice in the 21st Century Digital Economy

Jürgen Bott and Udo Milkau

1.1 Introduction

One approach to define what a ‘market’ is was given by Michel Callon, who suggested a difference between a market and a marketplace in English language (1998): ‘While the market denotes the abstract mechanism whereby supply and demand confront each other and adjust in search of a compromise, the marketplace is far closer to the ordinary experience and refers to the place in which exchange occurs.’ The term ‘marketplace’ conjures organised transactions between buyers and sellers like a street market or a shopping mall. The object of those transactions – goods or services – has a price, and this price will be paid at the end of the transaction.

From this perspective, a payment is part of a transaction (to settle the price), but is there a market for payments itself? Looking back in history, a British gentleman paid tradesmen, such as a carpenter or a tailor, in pound sterling (silver) but an artist or a barrister in guineas (gold); and perhaps he paid with a bill of exchange (paper) or even with grandma’s china (article of value) when he had run short of money. The payment itself had a price for one or both agents of the transaction, whether a monetary one or non-monetary such as delay, convenience, trade usances, image or trust. Today, customers perceive a variety of different options to pay: cash (banknotes), credit transfer, credit cards, PayPal, payments via iTunes accounts, iDEAL in the Netherlands, Faster Payments and Paym in UK, Swish in Sweden, Alipay or Tenpay in China, M-Pesa in Kenya, vouchers at the canteen, loyalty reward points at some merchants, Open Metaverse Cent (a system for payments in different virtual worlds), virtual currencies based on decentralised consensus systems (such as Bitcoin) and so on, depending on the situation.

This list is, obviously, a collection of different things: payment instruments, payments systems, payment providers and ‘digital alternatives’. From banking point of view this list seems to be a strange mixture. But these are the payment options customers can select (as consumers) or offer (as merchants). Carl-Ludwig Thiele, a member of the board of Deutsche Bundesbank, described the future of payments as: ‘colourful and manifold’ (Thiele, 2015, translation by the authors). This ‘colourful and manifold’ development is typical for an emergent phenomenon called a market, as Russell Roberts (2005) defined: ‘We call these [emergent] phenomena “markets”. Most of what we study in economics called markets are decentralized non-organized interactions between buyers and sellers.’

To understand payments as a market for different, dynamically developing payment options is a new point of view compared to a centrally planned and regulated payment system. On the one hand, a payment systems landscape may be static for some decades, but show an evolution over time including leaps forward in development. For example, the current ‘digitalisation’, such as the Internet and smartphones, has provided technical solutions at marginal differential costs and literally in the hands of the consumers, which triggered a wave of new payment offerings. On the other hand, payments cover only a small part at the end of a whole commercial process. They are closely related to the specifics of those different processes depending on industry, situation, frequency of transactions and relationships between the agents: a onetime payment in a restaurant with a tip is a different process compared to a regular, but varying payment to a utility.

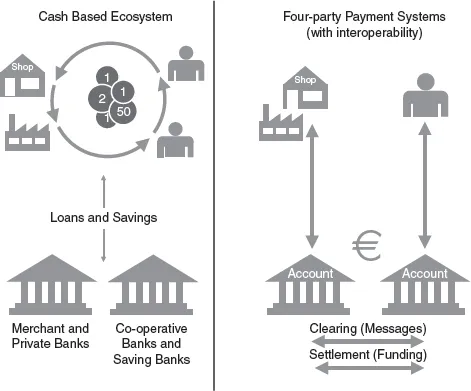

For a closer look at the market for payments and the development from cash to interoperable networks, centralised business platforms and decentralised consensus systems, it is worthwhile to start with a brief consideration of the transition from the cash-based ecosystem to the traditional four-party payments systems with a (salary) bank account, which emerged in the late 1950s/early 1960s in many European countries.

1.2 Industrialisation of payments

In many European countries, the days of the pay envelope ended in the late 1950s to early 1960s. This development illustrates the transition from a cash-based economy to electronic payment systems, which was initiated by innovative companies that recognised the benefits of electronic payments. As subject matter expert working in a medium-sized enterprise in Germany, Karl Weisser wrote about that development (1959, translation by the authors): ‘It is surprising that in the age of electronics and automation, in payroll accounting and wage payments many companies still use methods that belong to the time of day labourers’. Those innovators in the ‘real economy’ applied the industrial paradigm of electronics and automation to the banking sector and established the payment systems with the four parties: companies/merchants and their banks on one side and employees/consumers and their ‘retail’ banks on the other one. Before that point in time, the contribution of banks to connecting companies/merchants and employees/consumers was limited mainly to cash distribution and cash collection services. Banks’ core services – term, scale and risk transformation in corporate banking (equity, bonds and loans) and retail banking (saving versus loans) – were more or less separated from payments. With the introduction of the salary account, banks started to become an integrated part in the economic system along process chains such as purchase-to-pay.

The introduction of the retail current account, together with payment settlement between the banking sectors, was an enormous innovation because it combined the strength of banks in running accounts in a trusted, secure and stable manner with the industrial paradigm of electrification and automation of processes. With this first industrialisation of payments (see Figure 1.1), account-based services for retail payments have become part of core banking services. Electronic payments were established in the – regulated – space of banking with fees typically paid be the initiator of payments.

By including cashless payments services almost seamlessly into core banking functions, banks have enriched the processes of their customers. They contributed significantly to economic prosperity with integrated operational and financial features. With the further development of payment standards, the cash-based landscape changed to a highly efficient payments ecosystem, as central component current accounts are the hub for nearly all electronic payments and settlement of liquidity between the banks. As current example, in Germany today, nearly 80% of all payment transactions are ‘retail’ payments between consumers and merchants (bill payments by credit transfer, direct debits and card payments; ‘B2C’) or between companies and employees (including pensions or social benefit payments) and only about 10% are peer-to-peer payments between private customers (Milkau, 2010). It has to be remarked that about 80% of all payment transactions at the point of sale in Germany are still in cash (Wörlen et al., 2012), whereas much fewer point of sale transaction are made by cash in other European countries. Nevertheless, the introduction of the salary account in Europe (and similar card accounts) was the origin of the typical four-party payment models we recognise as fundamental for payment industry today (see for example Kokkola, 2010),1 and in reality there is a mixture between a cash-based part and an electronic payments part with a different ration from country to country.

Figure 1.1 Schematic development from a cash-based economy (left) to the current ‘four-party’ payment system with interoperable bank (right)

1.3 Sustainable efficiency versus dynamic disruptions in payments

The account-based payments systems developed over decades and were continuously optimised by the payments industry. The European Central Bank (Martikainen et al., 2012) reported empirical evidence that the electrification of the retail payments systems promotes economic growth. Enriching shopping and buying processes with the most adequate means of payment is of overall economic importance.

The culminating point of the development in Europe was the development of SEPA, the Single Euro Payments Area, as part of the political agenda to harmonise the European economy ‘to become the most competitive and dynamic knowledge-based economy in the world’ (Lisbon Agenda, 2000). SEPA supported the ‘Digital Agenda for Europe’ (European Commission, 2010): ‘Only in an integrated payment market will it be possible for enterprises and consumers to rely on safe and efficient payment methods.’ A recent study (PwC, 2014) requested by the European Commission DG Internal Market and Services reported that SEPA has: ‘Potential yearly savings to all stakeholders of €21.9 billion – a recurring annual benefit resulting from price convergence and process efficiency’.

The European banking community supported the long-term social benefits of SEPA from the beginning with a self-regulated approach between banks in Europe. The individual banks made significant investments in SEPA and the interoperability of retail payments in Europe because all partners adherent to the SEPA scheme are responsible for their individual payment systems. There is neither a ‘general infrastructure’ (for example a power grid or a telecommunication network) in payments, nor a ‘public good’ (like streets or railways).

Nevertheless, the development of sustainable efficiency and the success of the introduction of SEPA did not address a genuine flaw of the typical four-party payment model. As shown in Figure 1.1, this model comes with a decoupling of payments processing from the interaction between buyers and sellers. While information in the market for goods and services were exchanged ‘non-electronically’ for decades in the non-banking space, payment-related information travelled with the intra-banking processes of clearing of payment messages and settlement of funds between banks. The paradigm for the intra-banking space was interoperability.

As long as there was no technological innovation in the market, this model worked very well. But with the proliferation of ‘digitalisation’, disruptive innovations took place also in the payments industry.2 The term ‘disruptive innovation’ was coined by Clayton M. Christensen (Christensen and Bower, 1995; Christensen, 1997). Although his approach was criticised by others for the lack of predictive power (for example Danneels, 2004) and for the lack of reaching beyond technological product innovations3 (for example Markides, 2006), his model fit the changes in payments rather well. He proposed that (technological) innovations emerge in niches and take root initially in simple products, but then develop to disruptive competitors. Taking PayPal for example with its roots in two companies (Confinity and X.com founded in 1998/1999) for payments with Palm Pilot or, respectively, via e-mail, it had about 157 million active digital wallets at the end of 2014. Today, PayPal is a prototype for a ‘business platform’ with payment transaction within the PayPal ledger between different PayPal clients’ accounts on a prepaid basis. In parallel and especially in European countries such as Germany, PayPal developed into a new type of payments clearing service, facilitating payments flow between bank accounts of the clients outside PayPal. In this case each transaction is directly settled by (SEPA) direct debit or credit card transaction against the payer’s account and the payees usually transfer their funds at end of day or end of week to their bank accounts.

The result of this development since 2000 is an intermediation by new entrants in the payments landscape.4 These intermediators entered into the traditional relationship between banks and payment institutes and clients (merchants or consumers). These new entrants can be described from two different perspectives. From the point of view of the client, they provide the ‘colou...