Introduction

In an ever increasing number of policy fields, international cooperation under the conditions of ‘fragmentation’ is a reality. Fragmentation is the phenomenon of a multiplication of actors and growing atomisation, affecting goals, modalities, and instruments as well as the numerous operational and non-operational activities. The term ‘fragmentation’ is used in a number of areas and academic disciplines, including, in particular, the field of development cooperation.

To illustrate the fragmentation challenge, the construction of an Airbus A380 offers a compelling metaphor. Such an enterprise is characterised by ‘fragmentation’ in terms of actors, activities, processes and parts. Before such a plane can be assembled, the fuselage construction is completed in Germany and France, the United Kingdom is specialised in manufacturing the wing and tail, while the fin and pitch elevator are made in Spain. Once made, all main parts are then transported to Toulouse for final assembly (ECORYS 2009). The construction of the core aeroplane components requires a sophisticated planning process. An A380 comprises around four million individual parts which are produced by 1,500 companies across 30 different countries. For nonexperts in aircraft construction, it is an amazing feat that the production process will finally result in one of the most modern aircrafts in the world. It would be impossible to construct an aeroplane like the A380 without a highly specialised planning, construction and assembly process.

Where development cooperation is concerned, the A380 example provides insights on several basic facts. Each activity and each process consists of ‘fragments’. This is true for daily routine activities and complex processes of production alike. However, many routine and straightforward activities are quite different from the construction of an aeroplane. In the case of an A380 airliner, managing a highly specialised process involving many actors and activities is unavoidable.

Comparisons and parables have their limitations, though. It would be naive to assume that the construction of an A380 could provide directly transferable insights for the examination of the ‘fragments’ of development cooperation. Nonetheless, such a different perspective helps to identify the right questions: Is development cooperation an activity like building an aeroplane or are things more straightforward? If we need to construct an aeroplane: Are all donors doing similar things—for instance, are all donors building a tail? Is any actor, recipient or donor, in a position to play the role of the lead engineer or the CEO of the aircraft company? If development cooperation is a straightforward activity and a ‘mechanical’ process, are we all using the same methods and are the basic aspects organised in a similar fashion?

The search for insights from broader social science thought may illuminate even more fundamental and underlying concepts in development cooperation and the nature of development processes. By making William Easterly’s (2006) distinction between ‘planners’ and ‘searchers’, we may be implicitly using totally different basic concepts. In his view, the ‘planners’ in development cooperation use old and failed models of the past: the ‘financing gap’, the ‘poverty trap’, a ‘government-to-government aid model’, and an ‘expenditures equal to outcomes’ mentality. In Easterly’s perspective the methods of the ‘searchers’ display clear advantages: they imitate the feedback and accountability of markets and democracy to provide goods and services to individuals until homegrown markets and democracy end poverty in the society as a whole. An example of the more promising ‘searchers’ approach, in his view, is that of Nobel Peace Laureate Mohammad Yunus and Grameen Bank. Ben Ramalingam (2013) uses complexity theory to get away from technical ‘problem-solution’ approaches that are not suitable to ‘aid on the edge of chaos’. 1 Meanwhile, Jeffery Sachs’ (2005) approach is characterised by confidence in the planning capacity in the development area, whereas Easterly praises the ‘searchers’. ‘The man without a plan’ portrayed by Amartya Sen (2006) in discussing Easterly’s book would probably not be in a position to construct a flyable aircraft.

Against this background, the present edited volume attempts to offer a number of different perspectives on fragmentation rather than one specific answer to the challenges it poses in the context of development cooperation. This effort involves a conceptual and theoretical debate on the topic, along with various different qualitative and quantitative attempts to assess the phenomenon and to discuss ways of how to overcome its main challenges.

Fragmentation as a Key Concept in International Cooperation

‘Fragmentation’ as a concept is used to analyse the existing organisational structure, for example in the policy fields of international security and global environmental governance (Oberthür and Schram Stokke 2011; Zelli and von Asselt 2013; Biermann et al. 2009) and the structure of trade regimes (e.g. Cottier and Delimatsiss 2011; Snyder 2010). Thus, in discussions on international relations, the term is important for theoretical approaches and concepts. An increasing need for regulation to manage the processes of globalisation has led to the development of a number of international institutions and regimes. These institutions and regimes are characterised by overlaps, by the complex constellations of the actors involved, and by the management of linkages within and between the different fields of cooperation. When institution-builders of the 1940s established the main structures, they essentially began with a clean slate. The institutional landscape of today however is much more complex (Hale et al. 2013).

Recent debates look at innovative areas of international relations where new models of interaction and cooperation are applied. For example, the governance structure of the World Wide Web is unique and demanding in many regards (that is, in terms of the number of different actors, the role of public and private stakeholders, the interest of several countries to limit access to the internet etc.). In other words, the management of international relations looks quite different from cooperation patterns of the past: the ‘Orchestrating Global Solution Network’ is one example of innovations by organisational entrepreneurs (Abbott and Hale 2014); a current model for such a new multistakeholder initiative, which includes countries, civil-society groups and companies is, for instance, the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI). 2

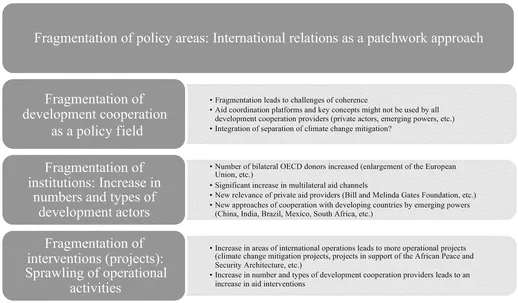

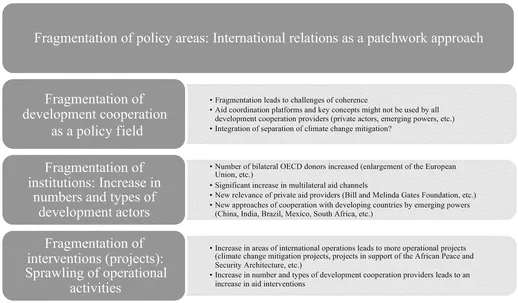

The need for specialised institutional solutions is clearly confronted with trade-offs related to institutional proliferation tendencies in a number of areas. Against this background, fragmentation can be seen as a concept to provide a better understanding of institutional arrangements and to analyse complex structures. In Fig.

1.1 we call this ‘Fragmentation of policy areas: International relations as a patchwork approach’ to point at the overlaps and gaps in terms of international regimes.

Fragmentation in the Field of Development Cooperation

These basic considerations also apply to the field of development cooperation (official development assistance, ODA). There is an increasing interest in fragmentation as a concept that is useful for the analysis of the aid landscape and aid architecture, the political economy of aid actors and the way aid is delivered. The interest in using ‘fragmentation’ as a starting point or a framing concept for aid does not only apply to the academic debate but also to the discussion among practitioners. The German Development Institute / Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE) organised an academic conference on the topic in 2013 where the idea for this book originated. 3 On the practitioners’ side, the Global Partnership Initiative (GPI) on “Managing Diversity and Reducing Fragmentation”, 4 a main forum for development partners and partner countries to reflect on related challenges, points to the relevance of the issue (see Chap. 15 by Pietschmann in this book).

Fragmentation leads to important unintended consequences for donors and partners alike, which can thwart their attempts to increase the effectiveness of aid. Each aid relation carries transaction costs that burden the administrative capacity of aid agencies; each additional aid relation complicates efforts to coordinate effectively, which increases the likelihood that sectors and countries are neglected, efficiency suffers and policy incoherencies are intensified.

In terms of academic approaches there has been an increasing number of pieces of quantitative empirical research on fragmentation in addition to fairly qualitative work on patterns and consequences of fragmented cooperation approaches (e.g. Nunnenkamp et al. 2015; Knack and Rahman 2004) (see Chap. 12 by Furukawa; Chap. 14 by Marquardt; Chap. 16 by Kasten; Chap. 11 by Nunnenkamp, Rank and Thiele in this book). To a large extent, the academic literature explains challenges through collective action theory and the political economy of aid that hinder a greater use of these instruments on the ground.

The term ‘fragmentation’ points to negative aspects of the complexity of development cooperation. At the same time, development cooperation and partner countries in particular might benefit from an approach that includes more competition stemming from diversity. This is why a continued diversification of development cooperation providers and approaches may also be viewed from a positive perspective: it increases the potential for mutual learning, innovation and competitive selection among the various different providers of development cooperation.

These differing assessments of the observed diversification of goals, approaches and actor constellations as well as the processes through which they are managed pose a challenge for the assessment of how to make development cooperation more effective. Whereas the critical viewpoint sees pluralism as an impending factor to increasing the effectiveness of aid, the more favourable stand views pluralism as beneficial to making aid more effective by creating a ‘market for aid’ and thereby more choices.

Drivers and Actors: Proliferation and Fragmentation Trends

Since the beginning of the 2000s in particular, there has been an acceleration in the trend towards the simultaneous proliferation and fragmentation of actors providing aid and other forms of international cooperation (Severino and Ray 2010; Janus et al. 2015). The increasing number of donors and other actors, as well as goals and instruments, has created an environment that is increasingly difficult to manoeuvre in. Critics argue that the continuous proliferation of actors and approaches has led to a fragmented development cooperation landscape in many aid-dependent countries. There are several aspects of relevance regarding this trend (see Ashoff and Klingebiel 2014).

In those areas of international cooperation not attributable to aid or only partly so, donors are increasingly establishing other approaches to cooperation and proposing forms of cooperation that mainly serve the interests of a specific sector. These cooperation models may deal with a range of matters, including issues of international security, the environment or research policy (see Chap. 14 by Marquardt in this book). An example of this is climate finance, whose volume has already reached a size similar to development cooperation. 5

The circle of multilateral aid institutions and EU donors has become even larger (see Chap. 13 by Reinsberg; Chap. 17 by Mahn; and Chap. 18 by Mackie in this book). Indeed, the high number of international institutions that offer multilateral aid leads Reisen (2009) to describe it as a ‘non-system’. As for the proliferation of providers, this is due in part to the creation of vertical funds, an increasing number of which have been set up since the 1990s, some of them endowed with considerable sums of money. Vertical funds are earmarked for specific issues, meaning they can respond relatively quickly and flexibly to new topics in a targeted manner (see Chap. 7 by Thalwitz in this book). New aid providers include several countries that joined the EU relatively recently, such as Poland and Lithuania, which contribute small amounts of aid and add to the proliferation process.

As new donors, dynamic middle income countries such as China, India and Brazil are of great interest in political and academic debates, given the considerable momentum they generate and the political implications of their involvement (see Chap. 9 by Bracho and Grimm in this book). Their cooperation with other developing countries is described as South-South cooperation, more horizontal cooperation relationships than traditional vertical cooperation between North and South. What disti...