- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

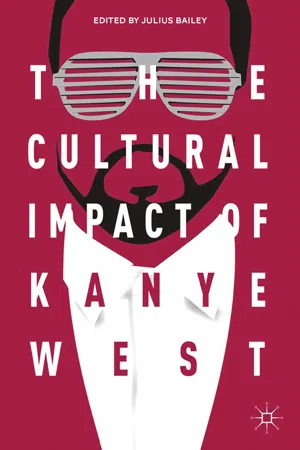

The Cultural Impact of Kanye West

About this book

Through rap and hip hop, entertainers have provided a voice questioning and challenging the sanctioned view of society. Examining the moral and social implications of Kanye West's art in the context of Western civilization's preconceived ideas, the contributors consider how West both challenges religious and moral norms and propagates them.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Cultural Impact of Kanye West by J. Bailey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Music. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Revisiting the Pharmakon: Artistic Gifts / Human Complexities

Chapter 1

Now I Ain’t Saying He’s a Crate Digger: Kanye West, “Community Theaters” and the Soul Archive

Mark Anthony Neal

Kanye West’s first collaboration with Jay Z on The Dynasty: Roc La Familia (2000) gave an early inkling on what would be the producer’s contribution to the sonic excavation of the Soul music tradition of the late 1960s and 1970s. The track “This Can’t be Life” features Beanie Sigel and Scarface (whose The Fixx, West would later contribute production), and is based on a sample from Harold Melvin and the Bluenote’s “I Miss You.” Though the song is not significant within the larger scope of West’s career, it placed Jay Z in a distinctly soulful context that would form the basis of the rapper’s career-defining The Blueprint (2001) as well as frame the early stages of West’s own solo career. At the foundation of West’s music prior to the release of his 2007 recording Graduation is recovery of the aesthetic possibilities of Soul music—a broadly conceived attempt to elevate Soul music as a classical American form, rooted in what Guthrie Ramsey Jr. calls the “community theaters” of Black life.1 Additionally, West’s attention to the Soul archive was also a method to balance his status as one of the most recognizable mainstream rap producers—a legitimate Pop star—with his creative devotion to laboring as a “Crate Digger,” as evidenced by famous lyrics that reference long periods of seclusion and a Cosby show reference to living in a different world.

Otis Redding was mining a popular music archive when he recorded “Rock Me, Baby” (1965), loosely based on Lil Son Jackson’s “Rockin’ and Rollin’” (1950) and “Try A Little Tenderness” (1966), a 1932 tune originally recorded by the Ray Noble Orchestra. But it was also recorded by a young Aretha Franklin and Sam Cooke prior to Redding. That Soul music emerged as the definitive soundtrack of the Black Freedom movement of the 1960s (Free Jazz notwithstanding) explains, in part, Redding’s intent: Soul music remains the clearest example of a genre of music that spoke across Black generations—a ripe site to serve the needs of “Movement” politics. Tommy Tucker’s “Hi Heel Sneakers”—a 12-bar Blues that would have been on-the-record players at virtually any “quarter party” in 1964 and whose melody you can hear in the original Sesame Street theme (1969)—is but one example of Soul music’s ability to mediate generational divides on a micro level.

One of the dynamics that marked the emergence of rap music in the mid-1970s was that it was thought to be sonically out of sync with the Civil Rights generation—the Soul Generation, if you will, to cite the name of an actual group from the period—a divide that would play out commercially, and in more than a few households, well into the early 1990s. Indeed, the classic retort that rap music was simply “noise” had as much to do with early rap music’s lack of melody as it did with how early rap DJs and nascent producers used previously recorded music in ways that older generations of Black listeners might have thought of as strange or foreign; there wasn’t a budding DJ in the period, trying to replicate a “scratch,” who was not cautioned by a parent to “not mess up the needle.” As any number of early hip-hop icons, such as Kool Herc (Clive Campbell), Grandmaster Flash, Grand Wizard Theodore, and Afrika Baambaataa, can attest, rap artists were always invested in Soul music, if only to locate break beats—the “get down” part—that they could reconstitute at the park jam or in the club.

The sonic divides that emerge among Black listening tastes—as much generational as it was regional and class based—spoke more broadly to actual divides, in terms of worldviews, political sensibilities, relationships with spiritual and religious institutions, and a range of others issues, that musical genres could never really address. Yet the genius of say Eric B and Rakim’s “Paid in Full” (1987) was that it sampled one of the few tracks in the 1980s that both Black youth and their parents might have listened to. That song, “Don’t Look Any Further, ”recorded by Dennis Edwards (with help from Siedah Garrett) featured production that replicated the electro-R&B of acts such as The S.O.S. Band and Midnight Starr, yet Edwards’s unmistakable vocals recalled the classic Temptations’s tracks he sang lead on like “Ball of Confusion” and “Papa was a Rolling Stone.” It’s important to remember that, during this era, it was a regular practice among so-called Urban Radio stations to eradicate rap music from their daytime programming, often only playing rap songs late at night on Friday and Saturday evenings. “Don’t Look Any Further,” along with hybrid recordings like Chaka Khan’s 1984 track “I Feel for You” (featuring Melle Mel), the R&B friendly production of Whodini (courtesy of Larry Smith), and Jody Whatley’s 1988 hit “Friends” (featuring Rakim) were important commercial efforts to bridge the listening gap, though most R&B stations were likely more interested in strengthening their audience base for advertisers.

The best depiction of the generational divide in Black listening practices was a 1996 Coco-Cola commercial (produced by Rush Media) in which an older Black father-figure listens to Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell’s “You’re All I Need to Get By,” while his son bobs his head to “I’ll Be There for You/You’re All I Need to Get By,” a track that borrows lyrics and melodies from the Gaye and Terrell original.2 By the time hip-hop producers, notably figures such as A Tribe Called Quest’s Ali Shaeed Muhammad, Gangstarr’s DJ Premiere, and Pete Rock of Pete Rock & CL Smooth, began mining the archives of Hard-Bop and Soul Jazz in the early 1990s, the sonic generational gap begin to close some, particularly among Black male listeners.3

The radio version of “I’ll be There for You/You’re All I Need to Get By” was remixed by one of the most critical figures of 1990s urban music, who is largely remembered for helping to craft a subgenre known as “Hip-Hop Soul”—a riff on a style known as “New Jack Swing,” often attributed to producer Teddy Riley, where rap music–styled production was melded with traditional R&B harmonies. Sean Combs was the Svengali behind the Bad Boy Entertainment label, which boasted artists such as Craig Mack (“Flava in Your Ear”), Total (“Can’t You See”), 112 (“Only You”), Faith Evans (“You Used to Love Me”), and most famously The Notorious B.I.G. In contrast to so-called serious producers—professional crate diggers—who privileged obscure source material, Combs often chose easily identifiable classic soul recordings. As Joe Schloss writes of “digging” in his influential study Making Beats: the Art of Sample-Based Hip-hop, “in addition to its practical value in providing the raw material or sample-based hip-hop, digging serves a number of other purposes,” including “manifesting ties to hip-hop deejaying tradition, ‘paying dues,’ educating producers about various forms of music, and serving as a form of socialization between producers.”4

Though Combs was often chided for lazy sampling practices (and there has long been dispute about how much Combs’s work was actually the product of the producers he employed at Bad Boy), his choices made sense with regard to the expansion of his brand; folk, who a decade earlier might have partied to Mtume’s “Juicy Fruit” or The Isley Brother’s “Between the Sheets”—both found on The Notorious B.I.G.’s debut Ready to Die (1994)—or Kool & the Gang’s “Hollywood Swinging,” which was featured on Mase’s breakout single “Feel So Good” (1997), found the music of Bad Boy Entertainment sonically appealing. Combs also used such strategies for pop audiences, using samples from David Bowie (“Let’s Dance”) and The Police (“Every Breathe You Take”) for his tracks “Been Around the World” and “I’ll be Missing You.” Given the sampling environment of the mid-1990s, in which licensing fees often made it cost-prohibitive for artists to sample some songs, Combs, with the backing of Arista/BMG and Clive Davis, could literally afford to be less creative. For artists and producers with less financial flexibility, they had to design methods that allowed them to undermine the logic of copyright law, notably the Bridgeport case, which effectively limited them to sampling three-notes from songs. These constraints led to practices such as chopping, which scholar Joe Schloss describes as “dividing a long sample into smaller pieces and then rearranging those pieces into a different order to create a new melody.”5

Sean Combs’s offers one of the most compelling frames to understand the emergence of Kanye West in the early years of the twenty-first century. With six solo releases and a duet recording with Jay Z, West is the most well-known hip-hop producer since Combs—and has arguably surpassed him in terms of public recognition. A decade after Sean Combs was criticized for being “all up” in the music videos of the artists he “produced,” West is a legitimate pop star and celebrity. Highlighting Scott Poulson Bryant’s observation more than a decade ago that Combs was his “own best logo,”6 West is indeed his own best brand. Yet unlike many before him, West’s attention to the craft of production is as much about the narratives associated with him, as are his now infamous public antics. Though few deny West’s status as an Artist—in the purest sense of the word—some of West’s most notable rants have been motivated by his perception that he, and Black artists in general, are given short shrift as serious artists.7

Whereas West has had the financial backing of a major label like Island Def Jam, his artistic strategy has been to balance his access to the most expensive sampling material with the creative ethics of a class of producers referred to as ‘Crate Diggers.” For West, who was a relative outsider, whose base was in the Midwest, his embrace of the life of a “crate digger” did important labor in terms of endearing him to hip-hop purists. As Schloss notes, crate digging “constitutes an almost ritualistic connection to hip-hop history,” as well as a “rite of passage” in the eyes of already established producers.8 Yet in light Schloss’s observation that a “sign of more advanced digging is the ability to find useful material in unexpected places,” West has also leveraged his visibility to celebrate a canon of Soul music from the Midwest, that like his own challenge to the hegemony of “bi-Costal” rap music, challenges the status of Southern Soul as the most aesthetically pleasing and historically important form of Soul music.

When Kanye Became a Pop Star

With the release of “Gold Digger,” Kanye West’s 2005 collaboration with Oscar winner and sometime R&B singer Jamie Foxx, West became a legitimate pop star. Certified multiplatinum, “Gold Digger” topped the Billboard charts in the United States and at the time of its release was the fastest selling digital download of all time. Released a year after the biopic Ray, which starred Foxx in his Academy Award–winning performance, the song generously borrowed from Ray Charles’s 1954 classic “I Got a Woman,” with Foxx reprising his “role” performing the song’s backing vocals as “Ray Charles.” The perception that “Gold Digger” was just a hot rip-off of a classic Soul recording—as part of a broader indictment of sampling practices—and West’s subsequent controversial statements regarding then President George W. Bush’s response (or lack of) to the New Orleans–based victims of Hurricane Katrina, helped overshadow the genius of the sample, and West’s own sampling practices. As Intellectual Property Law school James Boyle would later explain, “Gold Digger” was a crate digger’s dream, as the Charles original was as much a product of sampling, as was West’s version and “George Bush Don’t Like Black People,” the Legendary K. O.’s Hurricane Katrina–inspired appropriation of “Gold Digger.”9

West made a calculated attempt to use Charles’s music—he is rumored to have paid Charles’s estate one million dollars and 100 percent of the profits generated from the single for the use of the sample—to establish himself as legitimate pop star. “Gold Digger” was the second single from West’s second solo recording Late Registration, which was released on August 30, 2005, the day after Hurricane Katrina’s landfall in New Orleans. The recording sold more than 800,000 copies during its first week of release, and topped the Billboard album charts in the United States. Late Registration featured samples from other notable Soul artists, including Bill Withers, whose unreleased demo “Rosie” was featured on “Roses,” and Otis Redding, whose “Too Late” from The Great Otis Redding Sings Ballads (1965) appears on “Gone” (with Consequence and Cam’Ron). Perhaps the most famous Soul artist sampled on Late Registration, besides Ray Charles, was Curtis Mayfield. “Touch the Sky” (with Chicago-based rapper Lupe Fiasco), which samples Mayfield’s “Move on Up,” represents the closet distillation of a classic Chicago Soul sound in West’s music, though ironically it was produced by fellow Roc-a-Fella producer Just Blaze—the only track on Late Registration to not feature production for West.

Despite being produced by Just Blaze, who West shared an affinity with regard to the use of Soul samples and the practice of changing the pitch of the source material, “Touch the Sky” offers important insight to West’s own compositional strategies. As Robert Pruter notes in his book Chicago Soul, “Chicago during the soul era easily ranked as one of the major centers for the production of soul . . . Yet the city’s self-evident role has not only not received the proper amount of recognition by writers on popular music; too often it has been completely ignored.”10 One example of an artist who exemplified this dynamic is Syl Johnson, who until fairly recently—and in no small part due to his longevity and his copyright infringement case against West and Jay Z for “The Joy,” which also samples from Curtis Mayfield—had not received full recognition of his role in Soul music. As an A&R executive at several local Chicago labels and as an artist, Pruter writes that Johnson, “never made an impact with members of this nation’s critical fraternity . . . But if one examines Johnson’s career closely, one can find plenty of evidence that he created a body of work that ranked in artistry with most giants of the soul field.”11

West’s approach to Soul music is not unlike the road he traveled with regard to the dominance of so-called East Coast, West Coast and increasingly “Dirty South” biases in hip-hop, privileging communities—Soul-scapes, if you will—that have often been overshadowed by acts aligned with Motown (Detroit), Stax (Memphis), and to a lesser extent TSOP (Philadelphia). Choices such as The Main Ingredient’s “Let Me Prove My Love,” which is featured on Alicia Keys’s “You Don’t Know My Name,” which West coproduced, or his use of The Persuaders “Trying Girls Out” on his production of the remix to Jay Z’s “Girls, Girls, Girls,” are examples of West’s desire to expand popular knowledge of the Soul archive. Even when West has delved into the archives of the “Big Three,” as with the sample of Marvin Gaye’s “Distant Love” on “Spaceship” or most famously, with Redding’s “Try a Little Tenderness” on “Otis” from Watch the Throne (2011)—he has done so in a way that marked his uses as distinct artistic statements from the originals.

Many of the compositions on Late Registration were collaborations with instrumentalist Jon Brion, most well known for his work scoring films such as Magnolia (1999) and Punch Drunk Love (2002). It was with Brion in mind that West would later record Late Orchestration (2006), a live recording of his music backed by a string orchestra. With his focus on orchestration and ornamentation in music, West desired to highlight the “majesty” of Soul, not unlike similar efforts a generation earlier by Wynton Marsalis with regard to Blues music. Embedded in this desire was not simply the elevation of the music, but the lived realities of the people for which the music served so much purpose. Here West is illuminating what Ramsey has described as “community theaters” or “sites of cultural memory.” For Ramsey, these are sites that relish in “communal rituals in the church and the under-documented house party culture, the intergenerational exchange of musical habits and appreciation, the important of dance and the centrality of the celebratory black body, the always-already oral declamation in each tableau, the irreverent attitude towards the boundaries set by musical marketing categories.”12

Wake Up, Mr. West

Late Registration begins with “Wake Up, Mr. West,” one of many vignettes on West’s first two solo recordings, that feature a “faculty” whose voices are similar to that of the late Chicago-bred comedian Bernie Mac. The voice, which sonically represents West’s conflicted relationship with formal education—as borne out in the titles of West’s first three solo albums including College Dropout (2004) and Graduation (2007)—is also a metaphor for West’s layered ambivalence for his hometown—and the “community theaters” animated within the city. “Wake Up Mr. West” features a piano line from Natalie Cole’s 1980 recording “Someone That I Used to Love.” The song, written by Michael Masser and Barry Goffin, who also penned Diana Ross’s “Touch Me in t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Part I Revisiting the Pharmakon: Artistic Gifts / Human Complexities

- Part II Unpacking Hetero-normativity and Complicating Race and Gender

- Part III Theorizing the Aesthetic, the Political, and the Existential

- References

- Notes on Contributors

- Index