![]()

Part I

Mapping Religious Pluralism

Chapter 1

Poland: A History of Pluralism

Commenting on how history is taught in Poland today, historian Marcin Kula observes that the history of Poland is inevitably presented as the history of (ethnic) Poles (1996: 32). The fact that Polish historiography leaves little room for diversity might seem surprising given that for most of its history, Poland was an ethnically and religiously diverse state. Poland’s transformation from one of Europe’s most heterogeneous states into one of the homogenous nation-states in the world paralleled the increasing importance of both the Roman Catholic Church and the idea of the Polish-Catholic connection. Likewise, the state’s concern shifted from a focus on “religious others” to the issue of national and ethnic minorities, often perceived as bearers of religious difference. Understanding this transformation demands a processual approach in the scrutiny of historical events, policies, ideologies, and myths that contributed to the present-day status quo; a focus on a homogenizing rather than homogenous state and the practices that delegitimize diversity rather than a pure account of heterogeneity; and, finally, attention to the very process of making “Catholic Poland.” Of fundamental importance is the ambiguity of successive political regimes’ attitudes toward minorities, in particular their oscillation between rejection and retention of the previous systems, which challenges a number of widespread assumptions regarding religion, nationalism, and the respective regimes.

Analyzing the historical background of Rozstaje renders comprehensible the region’s present-day ethno-religious mosaic and sheds light on the roots of “hierarchical pluralism.” First and foremost, Rozstaje’s history epitomizes the ambiguities of state policies and political regimes’ manipulation of religious and ethnic identities. Brought together, a general account of events in Poland and of more specific developments in the region of Rozstaje casts light on broader questions regarding the accommodation of religious and ethnic diversity within nation-states, the role of intellectuals as myth-creators and myth-keepers, and the ambiguity inscribed into the discourse of multiculturalism.

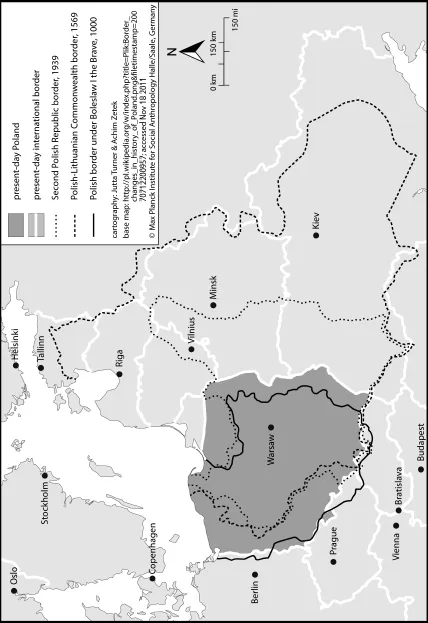

Some Notes on “Polish Tolerance”

The history of ethnic and religious diversity in Poland dates to the first alliances between the Kingdom of Poland and the Duchy of Lithuania (fourteenth–fifteenth centuries), which resulted in the creation of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1569. The Commonwealth is often referred to as the First Republic, since the executive power belonged to a king and the legislative power to an elected assembly of the nobility. Although the Lithuanian and Polish components of the union were formally equal, the dominance of Polish nobility and magnates was discernible. Due to the country’s expansionist policies, in the seventeenth century it occupied Royal Prussia, Ruthenia, Livonia, and Courland—that is, the territories that today form Kaliningrad, Belarus, Ukraine, Moldova, Latvia, and Estonia—becoming one of the largest political entities in early modern Europe. Among its three main ethnic groups, two, Polish and Lithuanian, adhered to the Catholic Church, while the third, Ruthenians, practiced Orthodoxy.

Several other ethnic communities settled in the country, either for economic (Germans) or sociopolitical (Armenians) reasons. The biggest population influx was caused by religious persecutions in Western Europe. The first to settle were the Jews, who, expelled from Spain, France, and Germany, migrated to the Polish kingdom from the twelfth century onwards. They were granted a number of privileges, as the monarchs saw in their settlement a potential for developing trade and the economy. Over time, they formed a separate class, and the First Republic became a center for the Jewish world, in terms of both demography and sociocultural developments. It must be noted, however, that despite the fact that some contemporaries referred to Poland as the paradisus Iudaeorum, such privileges did not always hold and pogroms did occur. The second wave of religious refugees arrived in the period of the Protestant Reformation, making the Commonwealth “the shelter of heretics.” Subsequent monarchs guaranteed religious freedom not only to the main currents of the Reformation (Lutherans and Calvinists) but also to minority congregations.

Map 1.1 Border changes in the history of Poland

The cornerstone of those policies was the signing of the “Warsaw Confederation” in 1573, which legislated the statutory protection of religious tolerance, guaranteeing equal rights in public and private life to the nobility and the royal burghers, regardless of their confession. Due to the fact that the confederation was signed in the period of the Counter-Reformation and religious wars in France and Germany, it is interpreted today as an attempt to prevent conflicts and a sign of the maturity of the contemporary politics. Historian Janusz Tazbir calls it “the great card of Polish tolerance” and highlights the admiration for the act among foreigners, quoting the entry in Diderot’s “Grand Encyclopedia”: “Poland [ . . . ] is a country where the least people were burnt for the fact that they made a mistake in the dogma” (1997: 32). What scholars do not often mention (e.g., Kopczyński 2010; Walczak 2011), however, is the fact that the resolution was not always observed and that the situation of religious minorities depended on the circumstances of the time and the outlook of the ruling king. Some confessions, such as Arianism, were eventually banned, while only the most powerful persuasions, namely Lutheranism and Calvinism, maintained their rights. Besides, praise for “Polish tolerance” tends to overlook the fact that no matter how outstanding such tolerance was at the time and no matter how impressive the range of civic and political rights, all this was limited to one estate (Walicki 1999: 263). Also, even if the dominant ideology was that of the “nation of noblemen”—people tied together not by ethnicity or religion but by membership in the nobility (szlachta)—it still involved a distinct hierarchy. As sociologist Antonina Kłoskowska points out, the Commonwealth was “a sociologically very interesting example of cultural polymorphism, but subordinated to the dominant Polish culture and not only the Polish state,” where nonethnic Poles recognized a hierarchical arrangement of ethnic and national elements, exemplified in the expression gente Ruthenes, natione Polonus [of Polish nationality and Ruthenian origins] (2001: 51). Open to newcomers, the nobility encouraged cultural assimilation, which led to the “Polonization” of Lithuanian and Ruthenian gentry and delayed their national developments (Kieniewicz 2009: 53; Walicki 1999: 266).

Yet another significant moment in the politics of religious diversity was the Union of Brest (signed in 1595, declared in 1596), which brought about the administrative and jurisdictional subordination of the Orthodox in the Commonwealth to the Vatican, although they maintained the Greek (Byzantine) rite. The main reasons for the Union were the Counter-Reformation, the Roman Catholic Church’s attempt to reinforce its position, and the poor status of the Orthodox clergy who hoped to be granted the same privileges as the Roman Catholic priests (Magocsi and Pop 2002: 480). However, the Union should be seen as the outcome of long-standing social, theological, and political processes.1 The idea of the Union was opposed by some Orthodox ecclesiastics, and the Ruthenian Church divided into the Uniate and the Orthodox Church. The process of ratifying the Union was protracted; in some regions, it extended until the turn of the eighteenth century (Himka 1999: 38). Eventually, there were two Eastern Rite churches, but their status varied over time. Despite promises and formal guarantees of equal status, Uniates’ position was lower than that of the Roman Catholics. This led many Ruthenian noblemen to convert to the Latin rite, which led, in turn to the Uniate Church being considered as the church for peasants, while the Roman Catholic Church was seen as the church for the nobility (Kłoczowski 2000: 133).

The political crisis of the Commonwealth in the eighteenth century coincided with a worsening social situation for non-Catholics. Accused of having sympathies with neighboring countries, non-Catholics were excluded from parliament, and apostasy from Roman Catholicism was banned and punished with exile. In the East, the war against Orthodoxy and the campaign for the acceptance of Union continued. According to estimates, at the time, 50 percent of the population were Roman Catholic, 30 percent Greek Catholic, 10 percent Jewish, 3.5 percent Orthodox, and 1.5 percent Protestant (Kuklo 2009: 222). All of these factors contributed to an increased influence and strength, albeit neither intellectual nor moral,2 of the Roman Catholic Church. The Counter-Reform offensive brought about the strong position of Jesuits, who, described by non-Catholics as “Spanish locust,” promoted the connection between being Polish and being Catholic, and, more generally, equated confession and language (Greek Catholicism and Orthodoxy with Ruthenian, Protestantism with German) (Tazbir 1967: 65). Clergymen enriched themselves and gained political influence; in the time of the “interregnum,” it was the cardinal who performed the functions of the interrex,3 often acting against the country’s interests. An ambitious reform program proposed by a group of enlightened and farsighted political leaders (of different religious backgrounds, among them clergymen) did not manage to save the country and, in 1795, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth ceased to exist, partitioned by Prussia, Russia, and Austria.

Partitions

Analyzing the period of the partitions (1795–1918) requires particular care, as the situation in the three regions differed substantially. Prussia and Russia pursued a policy of Germanization/Russification, to which the population responded with a defense of the Polish language and the defense of Roman Catholicism against Protestantism and Orthodoxy. Austria’s regime was comparatively more lenient, enabling cultural, political, and religious activities among the Polish, Ruthenian, and Jewish population and furthering the Ukrainian national movement.4 The latter was closely connected with the affirmative politics of the Habsburgs toward the Uniate Church, which, renamed as the Greek Catholic Church (1774) and provided with material resources, became the vehicle of Ukrainian national identity. The phenomenon of a flourishing Greek Catholic Church under the Habsburgs was even more remarkable, considering that the Uniates who found themselves under tsarist rule were forced to (re)join the Orthodox or the Roman Catholics (Magocsi 2008: 41). Generally speaking, Galicia—as the territory under Austrian rule came to be known5—was characterized by civic and political activities and a boom in educational, artistic, and literary endeavors in various languages (Magocsi 2005: 10), despite the fact that the political and cultural dominance of the Poles was asserted by the introduction of the so-called Galician Autonomy, which partly restored the Polish administration (1860). At the same time, due to widespread poverty and an undeveloped economy, the region also saw a large peasant uprising (1846)6 and significant out-migration, as people took their Galician identity and religious creeds to the United States and Canada. In brief, as many scholars who continue to explore “the idea of Galicia” demonstrate (Hann and Magocsi 2005; Wolff 2010; Zięba 2009), the region was a site of both interreligious and interethnic conviviality and fervent nationalisms, which, over subsequent decades, became mutually exclusive.

These observations invite us to address the situation in the part of Galicia known as Lower Beskid, the focus of this book.7 Lower Beskid was inhabited at the time almost exclusively by Rusyn population, who differed from ethnic Poles in language, material and symbolic culture, economy,8 and above all religion, since they practiced Eastern Christianity. Orthodoxy was maintained there for a relatively long time: the administrative structure of the Uniate Church was not fully developed until the middle of the eighteenth century (Horbal 2010: 244–5). The peripheral position of the region and the close network of parish churches fostered traditional, village-oriented life. But by the nineteenth century, the local population became a target of different national movements. The conflict between the “Russophile” and “Ukrainian” movements, associated with the parallel conflict between Orthodoxy and Greek Catholicism, was the most significant.9 The Austro-Hungarian rulers supported both the Greek Catholic Church and the Ukrainian national movement, perceiving them as counterweights to both Russian and Polish influences. At the same time, they were hostile toward the Russophile movement, which was in turn supported by migrants from America, who had converted there to Orthodoxy.

Returning to the question of the three different partitions of Poland, it must be added that, despite well-pronounced differences in terms of sociocultural activities, economic development, infrastructure, and levels of literacy, what was common to all was the “nationalization” of the consciousness of the Polish-speaking population, a process that occurred—albeit at different rates (e.g. Stauter-Halsted 2001)—across state borders and different strata of the population. Analyses of the role of literature and the press in this process tend to highlight the role of Romantic writers, who supposedly reinforced the connection between Polishness and Catholicism and encouraged the population to undertake several uprisings for independence (cf. Morawska 1984). The most frequently quoted author is Adam Mickiewicz, who, as it is often emphasized, defined Poland as the “Christ of the nations” and claimed that the sacrifice was a condition for its resurrection as a sovereign country (Mickiewicz 1952 [1832]). Not only does such a selective reading simplify the idea of Polish Romanticism10 but it also overlooks the fact that the presumed relation between Catholicism and Polishness in Romantic reflections was artificially strengthened in later decades. The frequently quoted work by Brian Porter (2001) provides a cogent deconstruction of that process, explicating the ambiguous role of the Catholic hierarchy toward the Poles at the time of the partitions and the no less ambiguous connection between religion and insurrectional activities. As Porter writes, “there were not very many ‘fervent Christians’ among patriotic activists” (2001: 295). While there is no doubt that Roman Catholicism—understood as religious devotion, habitual practices, and communal activities—played an important integrating role in Polish society, the relation between the institutional Church and society was different from what is often assumed today.

As a matter of fact, it was Positivism rather than Romanticism that brought about a new understanding of the “Polish nation.” The defeat of the last unsuccessful uprising for independence (1864) resulted in a positivist turn in thinking about the nation, leading to the reconfiguration of “nation as action” into “social nation” (Porter 2000) and new processes of “social deepening” and “ethnic narrowing” (Brubaker 1996: 417). Intellectuals and activists began to define nation in ethno-linguistic terms, suppressing class differences and striving to reach the working class and peasantry alike. Explaining these processes, Andrzej Walicki (1999) highlights the difference between “elite nationalism,” which argued in favor of a multiethnic state and patriotic citizenship, and “popular nationalism,” which led to the nationalization of the masses, stressed common ethno-linguistic base, and was closely connected with socioeconomic modernization11 (281). This new definition of nationhood, which now included all social classes but excluded the nonethnic Polish population, was to shape the politics of the Second Republic.

The Interwar Period

The Second Polish Republic, born after the First World War, was a multiethnic and multireligious state. According to the constitution of 1921, all citizens were granted equal rights regardless of their nationality or confession, though in practice the (ethnic) Poles were a privileged group.12 The number of minorities13 was assessed in two national censuses (in 1921 and 1931), yet both sets of statistics need to be analyzed with caution, given the instability of the country’s borders in 1921, and then the politicization of the 1931 census.14 Taking all these factors into account, Chałupczak and Browarek cite the following figures: among 32 million citizens, there were 68.9 percent Poles and 35.1 percent people of different national backgrounds (11 million) (1998: 21–5). The largest minorities were Ukrainians (15.7 percent), Jews (9.7 percent), Belarusians (5.9...